Each catalog card represented a book, painting, map, or other item housed within a library’s collection. Patrons would comb through the catalog, using the Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress classification systems to locate their desired piece of information.

In the 21st century, card catalogs may seem antiquated. Yet, they offer a tactile, immersive experience often lost in today’s digital era. There’s something special about physically shuffling through cards, guided by alphabetical or numerical order, and stumbling upon unexpected discoveries along the way.

Vintage card catalogs still have a place in our heart… and even our decor!

Each card carries with it the aroma of history (even just thinking about this topic evokes memories of that particular smell!), the silent imprints of previous readers, and the allure of an adventurous exploration through the stacks.

Nowadays, vintage card catalogs have become a coveted item among antique collectors, interior designers, and even DIY enthusiasts. These units have found second lives as unique furniture pieces in homes and offices, not only for the nostalgia value, but because these sturdy pieces retain their utilitarian appeal for storage of tools, crafting supplies, kitchen utensils, and the like.

Come along with us as we take a nostalgic look back at how we used to use library card catalogs, navigating the Dewey Decimal system the analog way.

How we used vintage library card catalogs

Article from The Union Appeal (Union, Mississippi) November 24, 1976

Do you know how to use the card catalog in the library? Do you ask the librarian about a certain book or do you look for it yourself?

Look for the most important item in the library; the card catalog. It’s that beautiful walnut cabinet with the many drawers. it contains cards on every book that the library system owns.

How do you find a book in the library? The first step in finding a particular book in the library is by looking in the card catalog. The card catalog is a file cabinet containing cards. This is actually similar to the index of a book.

Every title owned in the library system is listed in the card catalog, and to make it even easier, each title has more than one card. A fiction book has one card with the author’s name on the top line, and another card with the title on the top line.

Factual books have at least three cards: an author card, title card, and a subject card. All the cards are filed alphabetically in the catalog, as in a dictionary.

The type of book and where to look for it on the shelves is indicated in the upper left-hand corner of every card. For non-fiction, there is the Dewey Decimal Classification number on the book spine, identical to the call number. Fiction books are shelved by the author’s last name.

How the Dewey Decimal System works

Scrantonian Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania) Feb 4, 1968

How does the Scranton Public Library keep its collection of 173,311 books in order so that one can find the book one needs? We depend upon the classification system developed by Melvil Dewey in 1873, and still recognized as the basic system used in most public and general libraries.

In developing this system, Mr. Dewey thought of the divisions of knowledge found in books and decided to use the Arabic numerals in working out his first summary.

He used 000 through 099 for general knowledge — encyclopedias, dictionaries, outlines, etc. and 100 through 199 for philosophy.

Dewey then thought about the creation of man, and used 200-299 for religion. How does one serve his fellow man was his next concern and 300-399 was used for sociology. How does one communicate — and philology or language was put in 400-499.

Then came pure science, 500-599, technology or useful arts, 600-699; fine arts, 700-799; literature 800-899; and history, biography and travel 900-999.

Dewey Decimal Classification sub-divisions

Each of these main classifications are divided in his second summary.

To illustrate with one class — literature: 810 is used for American Literature; 820 for English literature; 830 for German literature; 840 for French literature; 850 for Italian literature; 860 for Spanish literature; 870 for Latin and 880 for Greek literature.

Other literatures are found in 890-899. These then were divided, and 811 became American poetry; 812 American drama; 814 American essays; 815 American’ speeches and orations; 816 American letters; 817 American wit and humor, and 818 American miscellanies. Thus we can use 821 for English poetry; 831 for German poetry; 841 French poetry; and so forth.

There is a consistency throughout his whole classification system which is immediately recognized when one studies the classification numbers used on books.

An example of this is found in collective biography — 920. One finds 921 used for philosophers, 922 for persons in religion and for saints, 923 for statesmen, rulers and social workers, 925 for scientists, 926 for technicians, 927 for artists and musicians, 928 for authors. We drop the last number, and use 92 for all individual biography.

Does one need to know and remember these classification numbers to find the books? No! The classification number (commonly referred to as the call number) assigned to the book is included on the catalog card found in the library’s card catalog.

Here, under one alphabet, is found a card representing each book in the library. There is a card under the author, the title, the subject or subjects and such added entries as series, joint author, etc.

Being guided by this call number, one is led to the book which carries the same number on its spine and is arranged in the library book stacks according to the call number.

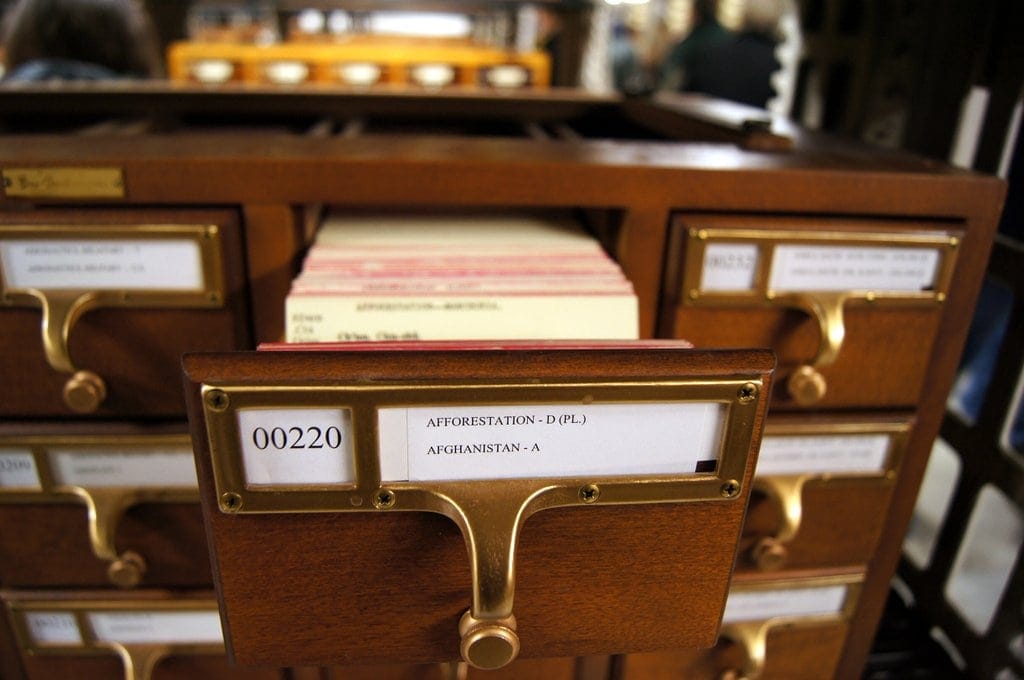

Drawers on the University of Michigan Library card catalogs

Library of Congress Reading Room (Open House)

00220: Afforestation – D/Afghanistan – A

Photo by Ted Eytan

Library card catalogs at Tulane University Library

Photo thanks to Tulane Public Relations

Card catalog, Burrow Library (1973)

Photo courtesy Ed Uthman

Wooden card catalogue in library with brass handles

Photo by Megan Amaral

Close-up of a card catalog in Chattanooga

Photo by Steve Hankins of hankinsphoto.com

Card catalogs from Harvard Law Library

Photo from Mellydoll

More vintage card cabinets/catalogues

Boston Public Library Johnson building card catalogs – 1970s

Sweet Briar College students standing by the library card catalog (1967)

MORE: Remember vintage library checkout cards & due date slips?

3 Responses

When I was in high school,out library had them and when I got a part time job there, I had to put the new “cards” in the drawers. Thank GOD for computers !

I wonder if any libraries still use cabinet-and-paper-based card catalogs. When I was in college, the library there retired the old cabinets and instituted a computerized system — and that was back in the mid-1980s!

Hello, I am looking for a way to determine value of my tiger oak library card file. Can you direct me to someone? Thank you