“Dear Children. I was born in the ‘Little House in the Big Woods‘ of Wisconsin on February 7 in the year 1867. I lived everything that happened in my books. It is a long story, filled with sunshine and shadow…” – Laura Ingalls Wilder

‘Little House’ books have big appeal (1975)

By Judith Serrin

To the people of Mansfield, Missouri, Mrs. Wilder was the lady who lived on Rocky Ridge Farm, just outside of town — a friend they might meet down at the post office or at the drug store and ask about the crops and the health of her husband.

“She was a lovely little person,” a friend recalled, white-haired and neatly dressed, spunky and outspoken when the occasion demanded it. Unlike many older people who have seen the country change around them, she was not given to talking about the good old days.

If the people of Mansfield knew she was famous — and they could hardly help but know it after the stories of Mrs. Wilder’s life were published in the 19308 and 1940s — they never treated her that way.

And for her part, Mrs. Wilder never talked about being an author, or receiving awards, or getting letters from thousands of children around the country.

“Not to me, and I don’t think she did to anyone,” says Irene Lichty, a good friend. The closest Mrs. Wilder ever came to mentioning it, Mrs. Lichty says, was “one day, she said to me, ‘Have you read my books?’ I said, “Why no, I haven’t. They’re children’s books, aren’t they?'”

Mrs. Wilder just kind of smiled and said, “You read them.” Once she did, says Mrs. Lichty, she realized how mistaken she had been.

Now the Little House books coming to TV

For three generations, the Laura Ingalls Wilder books have enchanted adults and children, historians and romantics, with her picture of life on the Midwestern frontier of the late 1800s.

This year, the stories have come to television, through “Little House on the Prairie,” starring Michael Landon. Laura purists — her books are the kind that are read and reread — may feel that the series is too much like a suburban situation comedy in home-spun. The sod house doesn’t look very soddy, said one librarian. Besides, Pa is supposed to have a beard.

Although television has brought new attention, an official of the American Library Association, Mary Dane Anderson, emphasizes, “The books didn’t need the TV show to make them popular.”

Ms. Anderson is the executive secretary of the child services division of the ALA and as such, is a professional Laura fan.

“I see the Laura books in homes where there are no other books,” she says. “It’s one of the few series that are being bought by mothers for their children.”

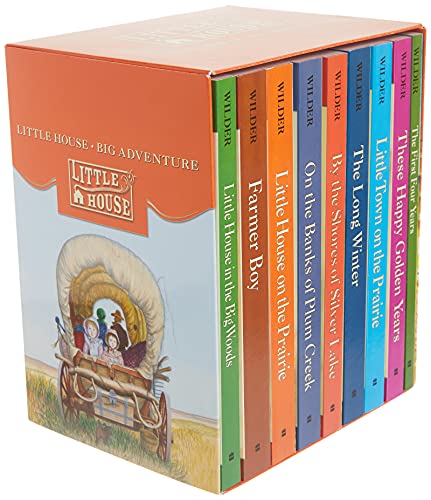

The nine Little House books (actually, only two of the series have “house” in the title) are among Harper & Row’s all-time best sellers. They have been translated into at least 18 languages.

A tenth book, published after Mrs. Wilder’s death in 1957, is a diary of the family’s move in 1894 from South Dakota to Mansfield, Mo. This year, Harper & Row has published “West from Home,” a collection of letters Mrs. Wilder wrote in 1915 describing a trip to San Francisco. At the time, her daughter, Rose, was a reporter for the San Francisco Bulletin.

In the letters, Mrs. Wilder tells her husband, Almanzo, about her growing interest in writing. She practiced with Rose and, when she got back home, notes a publicist at Harper & Row, “she decided she wanted to earn a little more money and write, too.”

Mrs. Wilder’s first published stories were reports about the trip to the Missouri Ruralist. She wrote for other Missouri papers and magazines, as a household editor and a poultry editor. Then one day, she bought a stack of nickel school tablets from the Springfield Grocer Co., wrote at the top of the first page, “Little House in the Big Woods,” and began writing the story of her childhood near Pepin Lake in Wisconsin.

When the tablets first came to the attention of the juvenile book editor at Harper & Row, the editor was so entranced reading them that she rode past her station on the commuter train home to Connecticut.

“Big Woods” contains one of the few historical errors in the series, notes Dr. Bernice Cooper, a professor of education at the University of Georgia, who did her master’s thesis on the Wilder books.

Although in real life Laura was about four or five years old at the time, in the book she is described as six or seven. “The editors thought a four-year-old couldn’t remember that much, so they changed the age,” Dr. Cooper says.

In tracking down the historical accuracy of the books, Dr. Cooper verified that the songs Laura mentioned were copyrighted by that time, that the magazines were published and that the clothes styles were accurate.

Clear memories and lots of hardships

She found Laura’s memory to be excellent. The books tell the way life really was, she says. “There were a lot of hardships. They had all the problems of illnesses, grasshoppers and the long winter when they all almost starved to death. But there wasn’t a lot of violence.”

Dr. Cooper believes the books are popular because of the universals involved — “the feeling of family love, security, just the growing up process.”

Boys like the books as well as girls, Dr. Cooper says, because Laura is not a sissy. And, she says, “the books are very popular with adults.”

In the Rare Book Room of the Detroit Public Library, a number of the adult fans bring their children to look at the Laura collection. A librarian unlocks a bookcase door and tenderly takes out the red tablets on which “The Long Winter” and “These Happy Golden Years” are penciled.

The library got the manuscripts in 1949, when the Laura Ingalls Wilder branch library was opened in Detroit. It was the first branch in the city to be named for a woman, and the first for a living author.

Mrs. Wilder was invited to attend but could not, because Mr. Wilder — she always referred to him in letters as “Mr.” — was ill. He died later that year at age 92.

A library with more than just Little House books in it

The Detroit branch library is one of two in the country named after Mrs. Wilder. The other is the branch of the county library in Mansfield, Mo., where hometown friend Mrs. Lichty says it sometimes seemed like the whole world recognized Mrs. Wilder’s worth before Mansfield did. But when she complained to Rose Wilder Lane about it, Rose would tell her, “They’ve always known my mother as a friend and neighbor. They don’t think of her as an author.”

Mrs. Lichty and her husband, LD, are curators of the Laura Ingalls Wilder museum in Mansfield. Visitors were always stopping by to see Mrs. Wilder, and after she died in 1957, her daughter asked the Lichtys to open the place for visitors.

The museum is beside the Wilder home, which was built from materials found at the farm site. The house is listed on the national registry of historic places. The fence around it was added after Mrs. Wilder’s death; she would never allow one built.

Fans need no explanation of what they find inside: The sewing box Almanzo made of cigar boxes for their first anniversary; Pa’s fiddle; the lap desk which held the $100 bill.

The house is open from spring to mid-October. Almost all who come know all about the books. Some are cultists who have made all the stops on the Laura tour: Burke, N. Y., the birthplace of Almanzo and site of “Farmer Boy;” Walnut Grove, Minn., the sod house site of “On the Banks of Plum Creek;” Burr Oak, Iowa, where Pa helped run the Masters’ Hotel; and De Smet, S. D., where Laura lived from 1894, and where she and Almanzo were married.

The real Laura Ingalls Wilder (author of the Little House books) and her husband Almanzo (“Manly”) Wilder

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s debut book, Little House in the Big Woods, lays the foundation for Little House on the Prairie series

Little House in the Big Woods – Book for children is written by former South Dakota woman (1932)

Author is sister of patient now convalescing in Huron Hospital; “Little House in the Big Woods” is pioneer story of Wisconsin

Being ill in a hospital has its compensations when one may travel into the woods and live the childhood days of long ago. At least Mrs. N. W. Dow [Grace Pearl Ingalls Dow], Manchester, finds it so, for a few weeks ago she was brought to a Huron hospital to receive treatment, and her sister, Mrs, D. N. Swanzey [Caroline Celestia “Carrie” Ingalls Swanzey] of Keystone came to be with her.

Then came “The Little House in the Big Woods,” a book just off the press, written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, a sister of Mrs. Dow and Mrs. Swanzey.

The story tells of 63 years ago, long before Mrs. Dow was born, when the Ingalls family lived in a log cabin on the edge of the big woods in Wisconsin. With Mrs. Swanzey residing, and probably stopping to add reminiscences of her own, Mrs. Dow was taken back to the childhood days of her sisters.

South Dakota pioneers

The Ingalls family moved from Wisconsin to De Smet, S.D., in 1879, where C. P. Ingalls farmed. Here Mrs. Dow was born. The author of the book, Laura Ingalls, married and moved to Mansfield, Mo., where she now lives, and where she wrote this book, her first.

“The Little House in the Big Woods” is written for children from 8 to 10 years of age, but appeals to adults for its refreshingly genuine and lifelike quality.

The little cabin stands miles from any neighbors and remote from any settlement. One learns how life was lived and gets a vivid picture of the hardships and the difficulties, as well as of the joys and adventures, of those early pioneer days. It will give boys and girls of today a real knowledge of one phase of pioneer life.

Face hardships

In those days, and in such remote parts of the country, each home was, of necessity, virtually self-sufficient. Each family depended on the crops raised in the clearing, on the food produced by domestic animals and wild animals, birds and fish, caught and killed by the father of the family, and canned, stored, salted down or smoked by the rest of the family for the time when they would be snowed in.

Life was very exciting when Christmas meant homemade toys and everyone doubling up with everyone else in order to fit two families into small space; when the “sugaring down” season meant that all the neighbors collected for miles around to attend the festivities, and when bears and wolves were not uncommon.

The characters are very much alive, and the portrait of Laura’s father, especially, is drawn with loving care and reality. The illustrations, done by Helen Sewell, have charm and catch the spirit of the books. The frontispiece of the book is a reproduction of an old daguerreotype made when Mr. and Mrs Ingalls were married.

Daughter is also an author

Mrs. Wilder’s daughter is a well-known American writer, Rose Wilder Lane. Her travel books are especially significant. Mrs. Lane has traveled extensively and knows five languages. Besides her shore stories, which have appeared in Harpers, Cosmopolitan, Red Book, and Ladies Home Journal, she has written more than 15 books. Some of these may be obtained at the Heron library, and are “Hill Billy,” “Cindy,” “He Was a Man,” “The Peaks of Shola.” Mrs. Lane writes of the Ozark mountains, where her childhood days were passed.

The Ingalls family hove always been interested in writing, Mrs. Swanzey had considerable experience on newspapers in South Dakota, and Mrs. Wilder has written for many farm magazines, although “The Little House in the Big Woods” is her first published book.