By 1908, materials were more readily available for people to make their own puzzles — and the popular novelties were soon found in households across the country.

Christmas puzzles: Ingenious homemade games for holiday gifts (1908)

New-York Tribune (New York, NY) November 15, 1908

The picture puzzle fad has received a new lease on life, which promises to make this coming Christmas a puzzle Christmas. The craze of men and women of many ranks of life, but chiefly fashionable people and brain workers, for putting together the picture puzzles began last winter — and by spring, the fad was well underway.

Private individuals, largely through the exchanges for women’s work, made good incomes from their jigsaws, the puzzles selling as high as $3 or $4 apiece. Everyone had picture puzzles and sent them to friends.

All summer long in mountain and seaside cottages, the picture puzzle craze raged. Its devotees were found on hotel piazzas, and no one went abroad without half a dozen picture puzzles to while away time on the steamer. Bridge whist suffered, and solitaire had its nose put out of joint entirely.

The interest has continued until the puzzles have become wonderfully elaborate and difficult, having as many as one thousand pieces. There are beautiful marquetry puzzles of colored wood from Holland, and the latest and most expensive there are silver puzzles which cost $33 and have designs etched or engraved upon both sides, making the solution much more difficult.

ALSO SEE: See what antique school supplies & educational materials were like in the olden days

A perfect holiday gift

For Christmas gifts, the puzzle which one makes oneself will be most in favor, for to it can be imparted that quality of appropriateness, which is the chief charm of a gift. The work requires more skill than might at first be supposed, and involves considerable expense.

The little jigsaws are inexpensive in themselves, but they break easily, and must be handled with care, and the work is tedious if done entirely by hand. The footpower jigsaw answers the purpose better, but is somewhat costly. One woman who is making some extremely clever puzzles purchased one of these saws secondhand, and paid $20 for it.

For the boards upon which to mount the puzzles, the thin poplar strip can be obtained of the woodman, and everything in the way of cigar boxes, the thin wooden boxes in which a jeweler sends silver by express — anything in the nature of a piece of wood which comes in the delivery from any of the shops — is treasured if it can be utilized for puzzles.

It must have the quality of cutting like cheese, with no tendency to split, and it must at the same time be tough and durable. It is heartbreaking after the picture has been mounted and the work is half done to break a piece and ruin the entire puzzle.

ALSO SEE: Antique scrapbooks: Layouts & scrapping ideas from long ago

Choosing the picture

Selecting the picture is a source of great amusement and a matter of some difficulty. Already the women who are making their own puzzles are having trouble in finding the kind of pictures they want, and the prices for those in greatest demand have gone up.

The illustrations from the French periodicals have done service for many puzzles, and a French picture, with a title, is interesting when put together.

Some of these French picture puzzles are a trifle outré in appearance before they are put together, and may give the friend to whom they are sent as a gift a slight shock. A shapely ankle appears here and a decollete bodice there — but in the complete picture, there is nothing more dreadful than lady of the ballet as she might appear upon any billboard.

Christmas supplements in colors, of which there are many in the English papers, furnish delightful puzzle pictures. There are Japanese prints which are artistic, but lack the “human interest” element. Black and white pictures are sometimes used, and posters are admirable.

“Can’t you get me that poster, three black cats sitting on a yellow fence?” wrote one woman, out of town, to a man friend. She knew that the masses of black in the animals and the large deep ground of yellow would make a puzzle effective when together.

The pictures are pasted upon the poplar board with great care, and in some instances, varnished. When dry, the jigsaw is put to work, and this requires infinite patience.

On a colored picture, some of the workers, following a certain method, cut out the different color first — and the smoothness with which design is followed does much to make a good effect when the puzzle is together.

One woman follows architectural designs and scrolls in her work. This gives an added zest to the worker and may help or hinder the one who puts the puzzle together. All the pieces have the edges carefully sandpapered after they have been sawed.

MORE: Antique toys: See what kids played with a long time ago – and that people collect now

Puzzle exchanges

Exchanging puzzles has been another development of the puzzle craze, and now a woman, after she has put a puzzle together so many times that it no longer presents difficulties, exchanges it with a friend for one which is new to her. Regular puzzle exchanges have been formed, and one puzzle may go the rounds of an entire circle of friends.

It has been said that a young girl in Boston started the puzzle craze, but that is denied by people who have followed it from the beginning, and there is every reason to believe that it received its first impetus in Newport last winter, among the people who spend the cold months there.

The story is that a little boy in Providence, a shut-in, began to make puzzles with his jigsaw to occupy his long, weary hours.

Some of the Newport people heard of the child and took the puzzles at first for his benefit, but before the winter was over, they became deeply interested in the puzzles themselves.

Now the craze is at its height in New York City, and many women are busily engaged making puzzles for Christmas stockings.

ALSO SEE: Rolling hoops used to be the coolest toys around

Confessions of a jigsaw puzzle maniac: A look back from 1973

By Ella Mazel – The Orlando Sentinel-Sun (Florida) November 25, 1973

Jigsawmania: The only human ailment that can be sold to its victims.

Onset: Occurs shortly after exposure to a package whose contents rattle when shaken well.

Severity and duration: Vary with the picture on the package and number of pieces enclosed.

Symptoms: Physical — eyestrain, stiffness of the joints, loss of sleep; mental — compulsiveness, disoriented time sense, diminished contact with reality.

Complications: Often a mild paranoia in the form of an unalterable conviction that a piece is missing, even when past experience has proven that one never (well, hardly ever) is.

Treatment: Unnecessary. Recovery is effected spontaneously the moment the patient establishes beyond a doubt that all pieces are present and accounted for.

Immunity: Not guaranteed by return to normalcy. After a brief convalescence, the victim is as susceptible as ever to a recurrence…

As a case in point, let me describe an acute attack of jigsawmania I suffered in the summer of ’69. I had worked unremittingly for seven months and, to decompress, I deliberately exposed myself to infection. Would you believe it was the night of the first moonwalk?

And where was I when man took his giant step? In front of the television like the rest of the family? No! With my jigsaw puzzle set up in another room!

While my ears were tuned to the lunar goings-on, the rest of me was held fast out of video range (I’ll admit to one or two peeks), as I silently sang the jigsaw theme song, “Just one more piece.”

ALSO SEE: Who were the Campbell Kids? Find out about the vintage cartoon mascots for Campbell’s Soup

Mind you, I was working just as hard on the puzzle as I had on my job. Long after the lunar module had blasted off and everyone else had gone off to bed, I sat there plugging away, bleary-eyed and aching — jigsaws and physical comfort are mutually exclusive, in my experience — defeated finally by sheer exhaustion.

Pierrepont B. Noyes would have understood my masochism, because he was probably the biggest jigsaw addict of all time. In February 1928, he and his nephew completed a custom-cut 10,000-piece puzzle of a West Point scene that measured 5 feet 1/4 inches by 6 feet 914 inches and had taken them an estimated 2,500 hours.

Lest you think these men had nothing better to do with their time, I might mention that P. B. Noyes was president of Oneida Community, Ltd., and in the process of writing a novel.

“The gigantic puzzle is now framed as a memorial to the tenacity and perseverance of the two men,” The New York Times reported, and it hangs to this day in Oneida’s Mansion House.

MORE: See the famous vintage Patsy dolls from the ’20s & ’30s

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, however, “The largest jigsaw puzzle ever made is believed to be one of 10,400 pieces, measuring 15 feet by 10 feet, made in 1954, at the special request of a man in Texas.”

Of course, we’re not told whether the Texan actually did the puzzle, so Noyes’ achievement may still hold first place. But speaking of size, did you know that the granddaddy of them all is the very earth beneath our feet?

A recent issue of National Geographic relates how geographers long ago observed “that the continents — Africa and South America in particular — would fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, if only they could be moved.”

Well, pursuing the new “plate” theory of land mass movements scientists ”will look for the driving mechanism, the ‘engine’ that moves entire continents and creates oceans. The search has been called the greatest jigsaw puzzle ever put together.”

On a more manageable scale, man-made puzzles today range from “minis” through what we might describe as bridge table, dining table, pool table, and ping-pong table size. As for the really limber, the floor’s the limit. Bigger is apparently better for a significant number of devotees.

Puzzles of up to 2,500 pieces are being offered by U. S. suppliers, but John Waddington of England has jumped from a 2,800 to a 4,000-piece series, with completed puzzles measuring about three by six feet.

ALSO SEE: About Tiddlywinks: The history of the old-fashioned game people keep rediscovering

Waddington alone admits to cutting up some 10 million puzzles a year. Though I haven’t succeeded in extracting any comparable figures from domestic manufacturers, there are apparently millions of us paying for the privilege of putting them back together.

Can we explain ourselves to those who look upon such a time-wasting pursuit with in- comprehension and/or disdain? How can you stay up till all hours pushing those pieces around, they wonder, when there are more creative, worthwhile things to do with your leisure time? Like fishing, playing golf, watching football, perhaps?

Pierrepoint Noyes characterized himself as “the sort of person who is profoundly irritated by being beaten, and my irritation takes the form of an egotistical and truculent determination to break through the stone wall of opposition.” He was explaining why he was such a good salesman, but I think he has also described the basic trait of the jigsawmaniac.

It all depends on whether or not we see a jumble of jigsaw pieces as “a stone wall of opposition.” If we don’t, we go on our merry ways doing a thousand and one other things. But if we do — well, that pile of inanimate fragments isn’t going to get the better of us! So what it comes down to, I suspect, is that, like the mountain climber, we do the puzzle “because it’s there.”

MORE: See inside old school classrooms from more than 100 years ago

And how did it get there? It all started innocently enough back in 1763, when a young English printer named John Spilsbury mounted a map on wood and “dissected” it into irregular sections “in order to facilitate the Teaching of Geography.”

Like all good ideas whose time has come, that of dissected maps caught on right away. Within a few decades, just about anything printed in the way of geographical, historical, pictoral, and religious subject matter deemed suitable for the instruction or amusement of children was grist for the British dissections’ mills.

In this country, dissected maps and pictures seem to have made their appearance in the 1820s, and they were advertised along with such items as building blocks, tops, dolls, and other “Mirthful Amusements for Merry Moments at Home.”

In the 1860s, they were part of the output of a youthful manufacturer of educational toys and games named Milton Bradley. By 1885, another enterprising young fellow, George Parker, had established a thriving business that included juvenile picture puzzles and dissected maps along with board games for children and adults.

In the 1890s, Rev. E. J. Clemens issued a two-sided series called ‘”‘Clemens’ Silent Teacher” that featured both U.S. and individual state maps (and sometimes an advertisement).

“Object teaching,” Clemens explains on the inside of a box cover, “is highly recommended by all educated persons, and all teachers of large experience say it is the most impressive and lasting method yet discovered of imparting instruction to young or old. Indeed, if we study nature very carefully, we will find that this is God’s method of instruction.”

To this day, puzzles are used for education through play. Simple puzzles with big, thick pieces are standard equipment in just about every nursery school, kindergarten, pediatrician’s office, and hospital playroom, as well as in the home. Repeated practice develops color and shape recognition, eye-hand coordination, and a sense of mastery over at least a small part of the environment.

DON’T MISS: Why people used to really love those iconic high-wheel penny-farthing bicycles

In fact, Dr. Louise Bates Ames, co-director of the Gesell Institute of Child Development, says “I would rather see young children doing puzzles than being pushed into reading too early.”

Children’s puzzles progress in structure from “match-ups” that have a separate space for each piece to those with a few pieces comprising a larger picture; to more complex inlaid and frame tray arrangements; then on up to regular jigsaws of increasing size and difficulty.

They are usually labeled with age ranges up to about 10, when they begin to merge with adult. But an individual child may decide to ignore such artificial classifications.

One mother swears that her son started with simple plaques when he was a little past two, was doing 150-piece puzzles in diapers at two-and-a-half, and whipping through 500-piece ones at the advanced age of three. She says she has witnesses.

Adults didn’t get into the act themselves until the early 1900s, when Parker Brothers came out with “Pastime Puzzles” that used high-quality reproductions of fine illustrations — and the year 1909 saw an early example of the American public’s propensity for “crazes.”

“It is estimated,” wrote a contemporary humorist in Collier’s, “that out of the 90 million of us, 10 million are suffering from puzzle pictures, 10 million more are just coming down with them, and 10 million more are convalescing and are beginning to take a weak, uncertain interest in theaters, baseball, automobiles, and love once more…

“All over the country dining room tables are being used to hold puzzle pictures, while the family is eating on the piano … The victim takes hold of puzzle pictures out of curiosity, only to find to his horror that he can’t let go. It hauls him ‘past dinner time, past engagements, across midnight and into trouble.'”

So tremendous was the demand that for over a year Parker alone had to virtually abandon all their other products while space and personnel were diverted to the manufacture of jigsaws. Once the jag fizzled out, puzzles were replaced in the public fancy by a succession of fads that included mah jong, backgammon, and crosswords. Then came the depression and, in 1932, the outbreak of a jigsaw fever on a scale never experienced before or since.

ALSO SEE: 50+ old-fashioned games: Take look back at what people played 100 years ago

Up to this time, puzzles were mounted on wood and hand cut by skilled craftsmen with what was variously known as a scroll, band, or jigsaw. Selling at about $15 for a 1,000- piece one, they were strictly a carriage-trade item after the crash, since if you were lucky enough to be working at all that sum probably represented more than a week’s wages. Now, suddenly, it was discovered that puzzles could be mounted on cardboard and inexpensively mass-produced by a mechanical process called “die-cutting.”

What a contemporary newspaper article described as “this latest conflagration” was sparked by the shipment in September 1932 of 12,000 die-punched puzzles from an unnamed manufacturer to an unnamed New England city. Before the fire had died down, some 200-300 companies were selling puzzles at an estimated peak rate of 2 million a week.

Puzzles-of-the-Week were plucked off newsstands at 25 cents each. Puzzles were exchanged through special clubs and rented by circulating libraries. Not uncommon were puzzle parties where, it was rumored, money changed hands when two teams were pitted against each other, losers paying a forfeit for each unplaced piece. Advertisers giving away puzzles as premiums were ordering a million at a throw.

It wasn’t until December of 1936 that the New York Times announced: “The country-wide craze for cardboard picture puzzles which nearly unhinged the national mind three years ago has run its course.” But a loyal following of dedicated fans remained, and a handful of firms — joined in the ’40s and ’50s by a few others — continued to provide a staple diet of inexpensive die-cut puzzles for adults.

ALSO SEE: Remember the old Clock-A-Word puzzle game from the ’60s?

Today these old-timers cater primarily to what the trade calls the “mass” market — the backbone of a multi-million dollar industry — through variety, discount, and drug store outlets. At any given time, their combined output consists of some 500 different subjects, of which the overwhelming majority have been scenic — street views and pastoral landscapes, coastlines and mountains, historical sites and tourist landmarks.

At any rate, for 40 years these have been — turned out as if by a sorcerer’s apprentice, and for 40 years millions of aficionados have been reassembling them.

One woman I know, who is apparently not untypical, has a standing order with her local supplier to call her whenever a new shipment of her favorite brand comes in. Milton Bradley received a letter from a 13-year-old girl who had lined the entire floor of her room with their puzzles and wanted to know how to preserve them — she was advised to transfer them to the wall. A family of six had special shelves built in their recreation room to house their accumulation, and a card catalog to keep track of them.

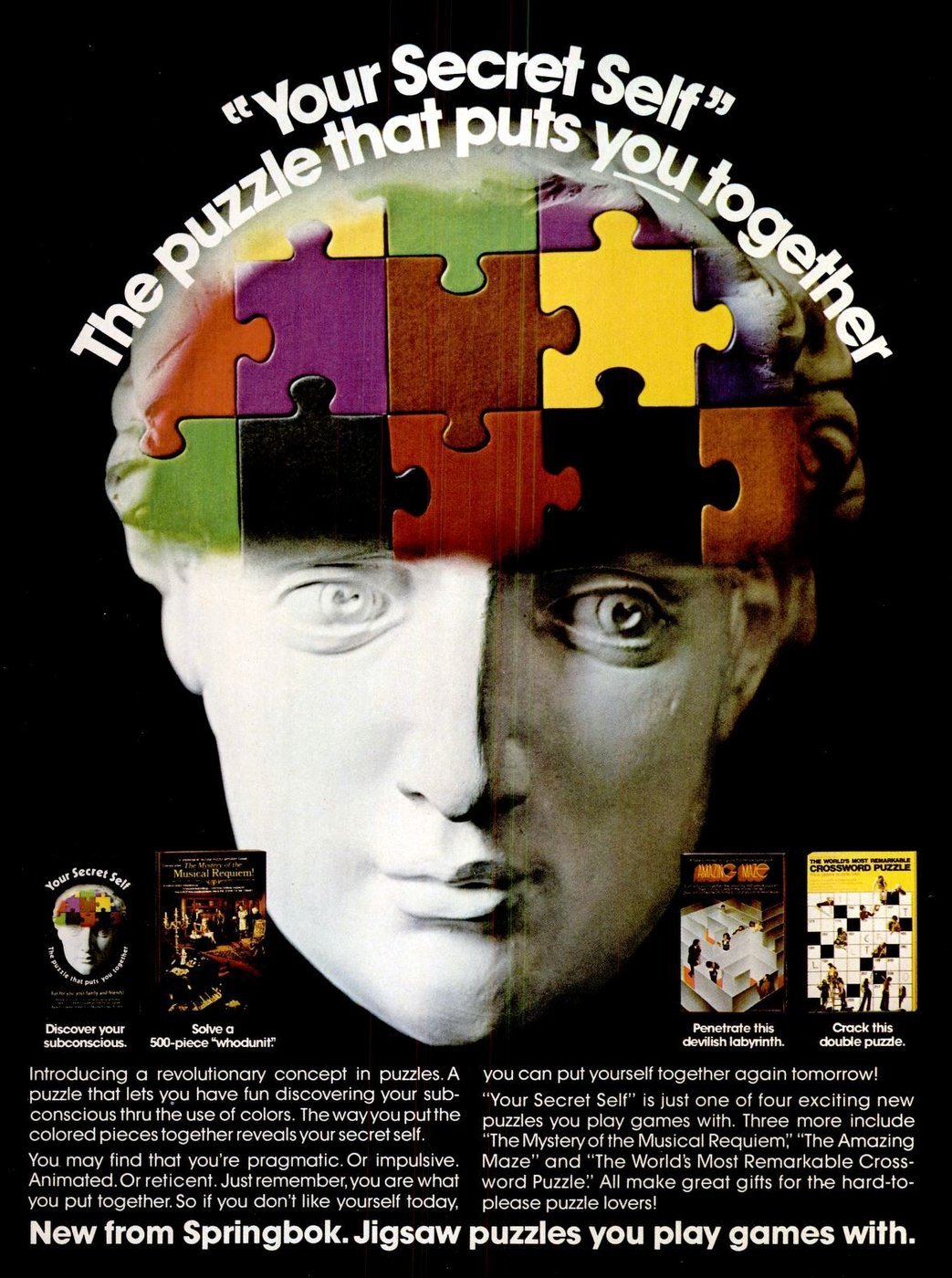

A new, “sophisticated” puzzling public was discovered in 1963, when Springbok burst upon the scene with quality reproductions not only of paintings but of tapestries and other exotic art forms. Others have followed their lead into hitherto untouched subject areas.

At department stores, bookstores, and stationery outlets, best sellers over the past ten years have included such varied fare as Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers, Psychology Today photographs, and Mickey Mouse.

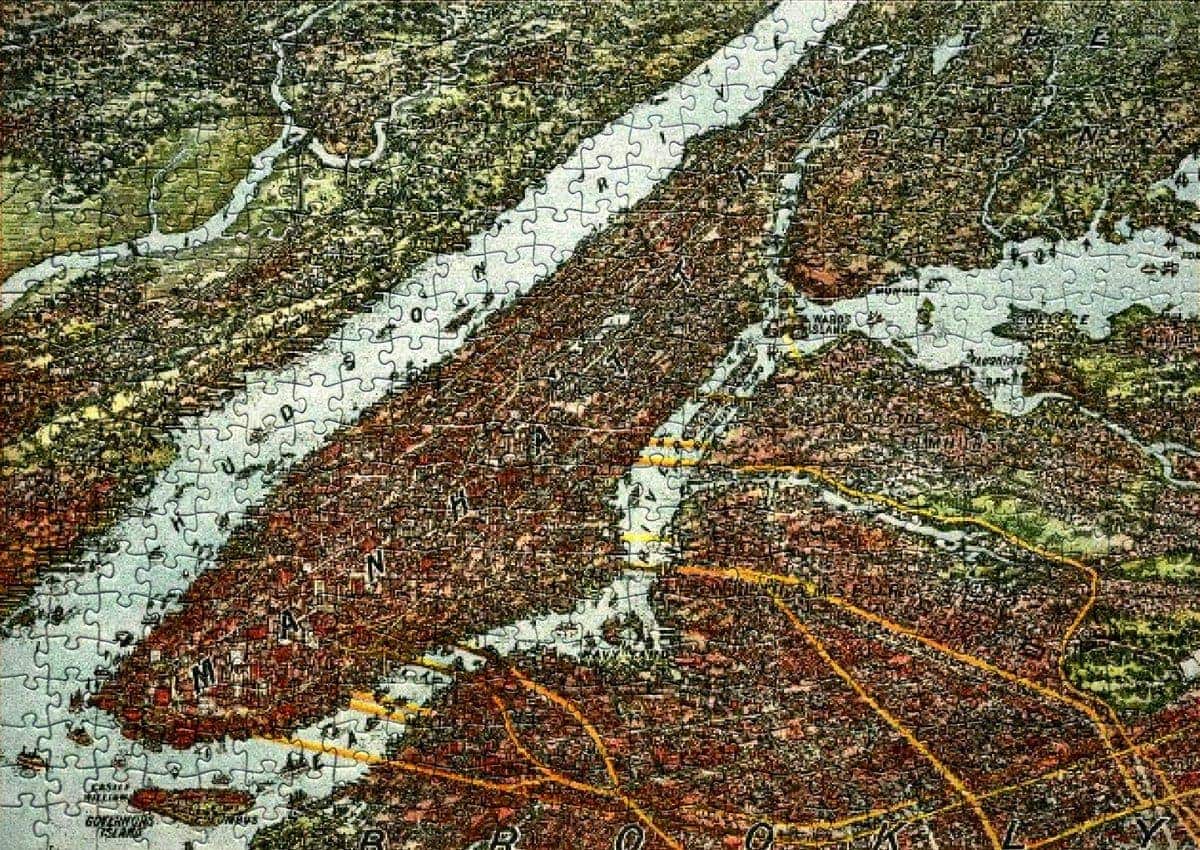

One manufacturer is doing a land-office business in maps of the New York City subway system, the Paris Metro, and what one writer recently described as “the most fiendish Christmas present of the year… a jigsaw puzzle of the Los Angeles freeways.”

Others have come up with such innovations as crossword, mystery, two-sided, and magnetic puzzles.

All this time, super-sophisticated “purists” have remained faithful to wood puzzles, the only ones that are truly “jigsaws.” Since they are hand cut, often to individual order, these are a lot more expensive than the die-cut ones.

ALSO SEE: How the classic Slinky toy was invented, plus see vintage variations

A further refinement demanded by the purist is the absence of a guide picture. “The greatest pleasure,” reads the label on a blank Victory box, “is derived from not knowing beforehand the subject which the puzzle will make and then to see the picture gradually form as the pieces are assembled.”

Even among those of us who do only the die-cut type, there are gradations in the ground rules we set for ourselves. For example, I select a puzzle according to the picture, but once I’ve started it’s a point of honor with me never to look at the cover; others think nothing of consulting the picture any time they come to a trouble spot. Most of us, I believe, put the “frame” together first; many make it harder by working outwards from inside sub-assemblies.

But that’s the beauty of puzzles. We’re not competing with anyone. We’re doing them entirely for our own satisfaction, and we’re free to go about doing them any way we please if we’re working alone, as so many of us prefer.

On the other hand, many of us do like to share them with our spouses, friends, and children. With Gerri and Herb, two jigsaw addicts I know, puzzles have always been a togetherness thing.

MORE: See vintage Fisher Price baby toys from the ’70s & ’80s

The kids have their own puzzles, but have always been allowed to help with mommies and daddies. Or if friends drop by of an evening — the right kind, of course — they may work together in intermittent conversation or companionable silence. Gerri confesses, though, to having favorite pieces that she palms so she can get to be the one to put them in at the end!

Sharing extends beyond our own homes as well. Recently I dropped into my friendly neighborhood public library in Larchmont, New York. Since my previous visit a new feature had been added — none other than a jigsaw puzzle exchange. Near the checkout desk was a set of shelves overflowing with rubberbanded boxes of all sizes and shapes.

Puzzles are either loaned or, in most cases, donated outright, and circulation has been lively right from the start.

So whether we buy, borrow, or exchange them, puzzles make a lot of us happy. We are pre-schoolers, nonagenarians, and all ages in between. We do them in homes, schools, and hospitals to relax, to learn, to kill time, and as physical and mental therapy. We are students; we are retired; we run the gamut of occupations and professions.

We like the Taj Mahal and the Alps, lions and kittens, Peanuts and pizzas, Van Gogh and Jackson Pollock. You can cut them in simple or tricky patterns; you can make them square, rectangular, octagonal, oval, elliptical, or round; you can give them to us flat or in boxes, cans, or tubes — but just give them to us.

NOW SEE THIS: Antique toys: See what kids played with a long time ago – and that people collect now