Especially when compared to the earlier Edison wax cylinders, the new “records” were much more durable, could be played over and over again, and were easy to share.

In fact, the 78 RPM phonograph records were a big part of what made the Victor company’s business so lucrative — their now-antique record players created a huge new market for their discs.

Throughout the era before radio, being able to play music (and comedy performances) whenever you wished on your own gramophone was a dream realized. No more would people have to rely on sheet music and a piano to have the latest tunes at home.

And while the machines have changed over the years, and the first discs are in museums, the songs haven’t stopped since.

The joys of owning a Victrola (1916)

Nationwide Victor Talking Machine Co. advertisement – May 18, 1916

The Victrola is the world’s greatest musical instrument — Do not confuse it with the cheap imitations that are now flooding the market.

The fact that the world’s greatest operatic stars sing for and endorse the Victrola is sufficient evidence to commend it to you. In your home, these great artists sing and play for you — Sousa’s and Pryor’s band will furnish you with a concert, or play for your dance.

Every instrument is reproduced perfectly on the Victrola. Tone quality is what has made the Victrola the unquestioned leader of talking machines.

Music for everyone on a Victrola record player

Own a Victrola, and you have the best. There is nothing that makes HOME LIFE MORE ENJOYABLE than the Victrola. It entertains everyone with its spirited music, funny stories and humorous sketches.

If you would have Sousa’s Peerless Band play for you the spirited marches by the “March King,” the catchy airs of the late opera, and the classical overtures by the great composers, they are all at your command.

The tone reproduction of the Victrola is so clear and perfect that one does not have to stretch his imagination to see himself seated in an audience, listening to this, the greatest band in the worlds Pryor’s Band, Vessella’s Band, Conway’s Band, The wonderful Victor Concert Band, also records by l’Orchestre Symphonique of Paris, Victor Herbert’s Orchestra, La Scala’s Orchestra, of Milan, Italy, all are represented in the catalog of Victor records.

Solos for the violin, cello, cornet, flute. banjo, xylophone, mandolin, guitar, by the most eminent artists living, are among the selections afforded by the Victrola.

The Victrola furnishes ideal dance music, and an immense catalog of specially arranged, up to date selections are now available.

To hear the Victor at its best, one should hear the records by the greatest opera singers, who make records only for the Victor. Caruso, Melba, Farrar, Homer, Gluck, Scott, and all the others of great note sing exclusively for the Victor Company.

The opportunity of hearing the reproduction of the voices of these best artists in your own home is in itself an education and a most refining influence.

If you have never heard the new Victrola, you cannot appreciate what great progress has been made in the manufacture of these instruments.

The artistic results that have been attained in the Victrola, distinguish it from other Talking Machines and cheap imitations that are now being forced on the market.

The history of the Victrola gramophone

Excerpted from an article in the Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut) December 8, 1974

The first apparatus for the recording and reproduction of sound… was the Edison Talking Machine, invented in 1877.

It consisted basically of a rotating cylinder covered with tinfoil, against which a needle attached to a diaphragm rested.

As the cylinder rotated, a screw pushed the needle across the cylinder’s surface, inscribing the sound vibrations in the air at the diaphragm onto the cylinder in a continuous helical groove.

The original machine used a stethoscope type headphone for listening, as the recording was too feeble to produce audible sound in a room.

MORE: How Thomas Edison invented his phonograph, bringing new sound to the world

Later on, hard wax was used as the coating on the cylinder, and the resulting sound was both stronger due to the improved strength of the material, and less “tinny.”

Meanwhile, in 1887, Emile Berliner invented the “gramophone,” which was remarkably advanced in concept.

Sound was transferred from the vibrating needle onto a zinc disc covered with a thin coating of wax, describing a spiral groove, as in modern records. The entire disc was dipped in acid, and the areas where the needle had scraped away the wax formed grooves in the zinc, creating a playable record.

But Berliner’s genius was in utilizing this to form a negative image disc by electroforming metal onto the original, and using this “mother” to stamp out thermoplastic copies of the original.

His system was superior, then, because of its mass production capability which the original Edison cylinder did not have. Edison attempted until 1913 to make his system compete, but eventually switched to the disc.

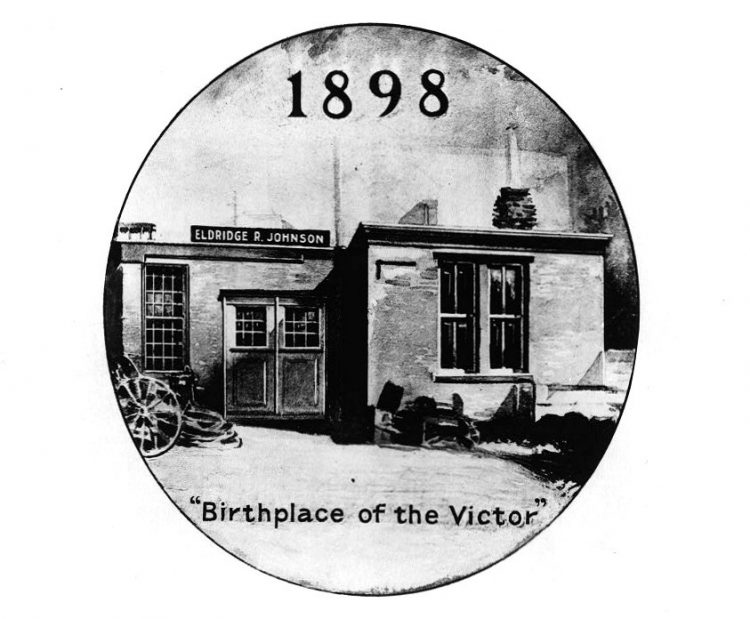

Berliner was joined by Eldridge Johnson in developing a spring-driven motor that would turn at constant speed, and together they founded the Victor Talking Machine Co. to manufacture the “Victrola,” which everyone associates with the picture of the dog listening to “His Master’s Voice.”

Berliner also introduced “lateral modulation” around 1900. Originally, all recordings were of the “hill and dale” variety, or vertically modulated: motion in the air was transformed into an up and down motion in the disc.

The problem was that the force holding the needle in the groove tended to plow through the hills and over the dales. With lateral modulation, the force to move the needle from side to side could be much less than the force actually holding the needle in the groove.

By around 1900, improved materials were creating sufficient acoustic output to let several listeners hear at the same time, and the development of the exponential horn around 1915 achieved near realistic sound levels for the first time, though at the expense of no bass and excessive high-frequency noise.

A radical change was brewing, however, via the invention by Lee DeForest of the Audion triode vacuum tube. This technology was applied to phonographs as early as 1915, but WWI delayed its commercial application until 1924 when Bell Telephone Laboratories demonstrated an electrical phonograph to the public.

By 1925, Victor and Columbia were issuing “electrically recorded” discs. Here the vibrations in the air were converted to electrical impulses by a microphone, amplified, then reproduced on a disc by a cutting head that responded with lateral motions proportional to the electrical signal.

The record was “played” by a pick-up head with the needle connected to a crystal that responded with an electrical signal proportional to the pressure on it. This signal was amplified and played back through a loudspeaker.

The improvement in sound was immediate and dramatic — surely this was “high fidelity” at its best. Nevermind the hiss, electrical hum, and interruptions every 5 minutes to change records; to the ears of the 1920s, this was recorded music at its best.

How to start and crank a gramophone (1890s)

Text from the first page of instructions from “E Berliner’s Gramophone: Directions for users of the seven-inch hand machine” (c1898)

The American Hand Gramophone reproducer is a talking machine which is both simple and effective, and will not easily get out of order, provided that the following directions are carefully kept in mind:

1. Place the machine before you, as shown in the picture, resting the arm fully upon the table, and turn the hand-wheel with a wrist movement at the rate of about 150 times a minute.

To acquire this regularity of motion, practice it a number of times with the lever and sound-box lifted off from the turn-table. Hold the handle loosely, so that it slides readily through the fingers.

2. The standard velocity of the center turn-table for 7-inch plates is about 70 revolutions a minute. A more rapid motion will raise the pitch of and sharpen the sound; a slower motion will deepen the same. First get the speed and then place the reproducer and needle into the outer groove or the next one.

3. The needle points should be firmly set, and must not be removed until worn off — generally after about 12 or more reproductions for 7-inch discs, if the same plate is used many times in succession — because the edges gradually forming might scratch the plate or render the sound less pure.

Rube Goldberg comic strip about Victrola record players (1916)

Try This System of Indexing Your Victrola Records — By Goldberg

An old Victrola: Journey into the past with a turn of a crank (1959)

Family inherits 1915 side-winding Victrola, batch of records of no-fi era

by George McCue – St Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri) March 22, 1959

Several times in recent years, our household has advanced to the brink of acquiring new record-playing equipment, and each time it has pulled back.

Our spasms of renewed interest always seem to come just as the recording industry is on the threshold of some splendid new development that will produce even higher high-fidelity. Then we always say that we will bide our time just a little longer to see how things work out.

One day not long ago, while we were sitting tight and biding our time, our devious progress in the recorded arts went straight into reverse.

Kinsmen, shipping us an inherited piece of furniture, sent another item for good measure. It was a Model XVI, Type H, Victrola. According to a label pasted inside the record compartment, it was made in 1915.

The arrival of this relic out of the low-fidelity, or “lo-fi,” or it might even be said, “no-fi” past, caused a good deal of excitement. We walked all around it, taking in its imposing 52 inches of height and its flared-out corners, carved in leaf and scroll designs in opulent emancipation from the straight line.

Here was an instrument not intended to fit reticently into a grouping of living room units placed flank-to-flank. It was not designed to look, in its off hours, like a buffet, or a commode or a lamp table.

It was designed to look like exactly what it was, the Victrola XVI, Type H, and to stand alone in its glory, with chairs, sofas and other appointments arranged in subsidiary positions around it.

Except for a dulling of the varnish, this mahogany edifice was in what collectors call mint condition. For years it had stood in a seldom-used parlor in a small town of north Missouri, its original owner a dentist who, after his wife’s death, just locked it up.

My father-in-law, a physician in the same town, came into the Victrola after tending the dentist, an old friend, for many years.

The manual that came with it stated that our model of the Victor Talking Machine cost $200. Not $199.95, but a clear, cool, man-to-man $200.

It was about the midpoint in a line that began with the Victor Jr. Gramophone, which sold for $10, and reached its summit with a model called the “Auxetophone (Pneumatic Victor),” at $500.

MORE: When 45 RPM vinyl singles & their record players debuted, it was a big deal

“The Victor Talking Machine is not an instrument requiring great or expert care,” the manual began reassuringly. It told how to remove the instrument from the packing case, and where to find and how to install the motor and the pickup arm, which it referred to as the “taper tube.”

Once the purchaser had mastered his excitement, and had got straight as to trip “D,” yoke “A,” knob “B,” and brake lever “E,” the phonograph was beautifully simple.

You put on a record, gave a few turns to the crank that stuck out from the right side of the cabinet, lowered the needle into the groove — keeping a firm grip, because the sound box assembly weighed close to a pound — and then sat down to listen. No warmup, no bass and treble controls, no record compensator.

The only maintenance needed, the manual said, was occasional lubrication of the spring motor, and a drop of oil now and then on two or three bearings and the friction leather of the brake. No tubes, no switches, no service man.

Of course, the hi-fi devotee could be expected to add: and no tone. The little mica diaphragm that is the old phonograph’s entire means of converting needle vibrations into speech and music has its limitations, but it seems a wonder that it can reproduce anything at all.

Our youngsters quickly rummaged through the record albums, stored on two shelves in the lower part of the cabinet, for an old favorite that they knew would be there, ”The Preacher and the Bear,” sung and recited by Arthur Collins.

We fitted a needle into the sound box, wound up the motor and were wafted back to a childhood when the predicament of a preacher treed by a bear and imploring, against the sound of menacing growls, “O Lord, if you can’t help me, for goodness sake don’t you help dat bear,” was ripe comedy.

Like archeologists reconstructing a past era by dipping into a cache of artifacts, we explored the other albums. They were stocked with a fairly numerous sampling of what stirred, amused and edified family groups at a time when much of the Middle West retained a semi-rural character, with few outside diversions.

Among records that showed signs of frequent use were several small discs, about the size of today’s 45 r.p.m. records, of Swiss yodelers, and quite a few 10-inch records, mostly hymns, gospel songs, Civil War songs and plantation echoes, done as tenor solos and male trio and quartet numbers.

The tenor solos are of the stylized nasal quality that is imitated today in the spirit of savory reminiscence and parody, but these were done straight.

The perpetrator of “Where Is My Wandering Boy Tonight?” who is left anonymous on the label, was giving it his all.

The Chautauqua Preachers’ Quartette, which sounds like all its members were tenors with handlebar mustaches, were not doing takeoffs of an old-time male quartet — they WERE an old-time male quartet.

In their “The Boys of the Old Brigade” and “The Church in the Wildwood,” they were taking a calculated tug at heartstrings in many a country parlor, such as the one where these records were played in what our children callously refer to as “the olden times.”

The Neapolitan Trio (violin, flute, harp) is there with ”The Herd Girl’s Dream,” a genteel, nineteen-fifteenish Sunday afternoon sort of record. There is Alma Gluck, the sweet singer of the 12-inch section, with “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.”

MORE: Remember those mail-order record clubs that offered vinyl albums & tapes for a penny?

There is quite a spate of Old Harry Lauder. And Homer Rodeheaver, the bouncy baritone soloist, choir leader and trombone blower, the first of a long line of gospel singers to make a name for himself on phonograph records, singing, or perhaps rendering is the word, “If Your Heart Keeps Right” and “Brighten the Corner Where You Are,” and carrying the melody to a Mrs. William Asher’s alto on “In the Garden.”

This same tuneful old favorite, which is still going strong in Sunday School intermediate departments and around the evening fire at summer camps, is also on a record by Marion Talley.

This would have to be one of the newer sides in the collection, for Miss Talley’s brief blaze of glory came in the early 1930s — the Kansas City soprano who showed operatic promise, became the prima donna at the Met and then just took up wheat-farming. I wonder what’s become of Talley?

Most of these selections glow with the mauvish aura of a period that now seems far-off and quaint, yet it was not so long ago.

Those who were around then will recognize this as the kind of music and fun that pulled in the buggies from over the countryside for afternoon and evening performances in hinterland opera houses, Masonic halls, Chautauqua tents set up for one-week stands, in tent revival meetings and tent repertory shows.

It was a time when outlying communities responded avidly to road show offerings of wholesome, refined entertainment that you could take your best girl, or your sister or your mother to, and all these supplied it.

ALSO SEE: See 20 vintage jukeboxes, including Classic Rock-Ola & Wurlitzer machines

There would be speeches by Congressmen and other masters of the resounding phrase who would hit the road with offerings like “The Cross of Gold,” “How to Be Happy,” ‘Needs of the Hour,” “Acres of Diamonds,” ‘More Taffy and Less Epitaphy” and “Yellow Peril,” and the music provided breathing spells in between these excursions of the mind.

Phonograph records helped fill the long gaps between shows, and catered to the appetites whetted by them.

Some of the oratory may have been put on records, but if it was, my father-in-law’s dentist friend, who was a perennial Chautauqua season-ticket buyer, didn’t have any in his albums. They run to music and monologues.

Victor made a good many cuttings of the monologues of Ralph Bingham, an old Chautauqua hand who danced, sang, played the piano and violin and acted out amusing stories for an hour-and-a-half stint. Bingham is affectionately recalled in last year’s Hastings House book, “Culture Under Canvas,” by Harry P. Harrison and Karl Detzer.

“Whether he winked, scowled, yawned, whistled or hummed, the people liked it; but they laughed hardest when he laughed, which was much of the time,” they said.

ALSO SEE: See vintage drugstores 100 years ago, selling lots of things you can’t (legally) buy anymore

One of Bingham’s specialties was dialect stories like those of his record, “Jests from Georgia” and “Mrs. Rastus on the Telephone,” which came with the old Victrola.

These would be beyond the pale now, but it doesn’t seem to have occurred to anyone then that they reflected unkindly on the Negro race, any more than the Uncle Josh sort of humor reflected on the white race.

On the old records in the old parlors, they brought back the bright-lighted stage, the spectators on folding chairs and on planks, tirelessly plying their fans, the smell of hot canvas and the excitement of the week-long array of celebrities.

The craving for a hearty laugh and the dearth of anything to provoke it is eloquently testified to in the indications of hard wear on a series of 10 sides about Uncle Josh, classified on the labels as “Rural Comedy,” “Rural Dialect Monologue” or “Laughing Story.”

Uncle Josh was a specimen of the classic rube character, played by Cal Stewart. His record series of the hayseed from Punkin’ Center was almost as widely distributed as Rover Boy books.

There are records of Uncle Josh in a Chinese Laundry, On a Bicycle, At the Circus, Having Troubles in a Hotel, On a Street Car, “On” An Automobile, on a Trip to Boston and on Two Visits to New York City.

DON’T MISS: See Thomas Edison’s mansion home, inside & out

Let us sample some of the Uncle Josh humor, taken verbatim from “Uncle Josh’s Arrival in New York City.”

We turn the crank, put in a fresh needle, switch off brake lever “E,”‘ carefully lower the sound box into the groove and hearken to a twangy voice from out of the past:

“Well, I guess I had just about the doggondest time gettin’ here to New York to see you folks I calclate ye ever heerd tell on. I was aridin’ along on the keers a-comin’ here and I had the ticket in my hat.

“Well, I put my head out the window to look at something and the wind blew my hat off, and I lost my darned old ticket. Well, the conductor made me buy another one. I had to buy two tickets to ride once.

“But I fooled him. He don’t know a thing about it, and when he finds out he’ll be just about the maddest conductor on that Pennsylvania railroad. I got a round-trip ticket, and I ain’t a-goin’ back.”

That doesn’t come off as very side-splitting in print, and the amusement with which we heard was mainly at the idea that it had ever been considered funny.

But it brings back a mellow recollection of listening to Uncle Josh records with a roomful of young cousins, with the sweet smell of hay blowing in through the open window, and of having to replay them because shouts of delight had drowned out some of the lines. And of grownups in the background still relishing the records they had heard so many times that they knew every rasp.

The Victrola XVI, Type H, may have strained out some of Alma Gluck, but it delivered Uncle Josh entire.

He and the no-fi phonograph were made for each other, and while our ear is more demanding now and our taste more critical, we can picture the family circle around the old phonograph and envy its readiness for laughter.

The venerable talking machine that could summon up laughter with a few turns of a crank and a drop of oil every now and then on the bearings and the friction leather excites our admiration. We have installed it in a suitable corner, where it stands in quiet dignity, still ready to perform any time it is called upon.

ALSO SEE: How do you choose a good turntable? Old-school tips for the best record players

Victrola record players: “His Master’s Voice” (1920)

The trademark of supreme musical quality — It means the world’s largest and greatest musical industry

Twenty years ago the talking-machine was a triviality. Today the Victrola is an instrument of Art. The exclusive Victor processes have lifted the making and the playing of musical records into the realm of the fine arts and rendered them delightful to the most keenly sensitive ear.

Opera singers and musicians of worldwide fame are glad to be enrolled as Victor artists.

Every important improvement that has transformed this “plaything” into an exquisite and eloquent instrument of the musical arts originated with the Victor. The Victor plant, the largest and oldest of its type in the world, is the world-center of great music.

No other organization in the world is so qualified by experience, by resources, and by artistic equipment to produce supreme quality as the Victor Company. Its products convey more great music by great artists to more people throughout the world than all other makes combined.

The pioneer in its field, the Victor Talking Machine Company today remains the pre-eminent leader.

The famous trademark “His Master’s Voice,” with the little dog, is on every Victrola (look inside the lid) and on the label of every Victor Record. It is your guarantee of the highest musical quality.

Look for it. Insist upon finding it. If you wish the best, buy nothing which does not contain this trademark.

Victor Talking Machine Co., Camden, N. J. — New Victor Records or sale at all dealers on the 1st of each month

NOW SEE THIS: See 20 vintage jukeboxes, including Classic Rock-Ola & Wurlitzer machines