Computers in the 1960s: How they worked, who used them, and their legacy

In an exclusive 1967 interview with US News and World Report, John Diebold, a prominent authority on computers and automation, shared insights on the revolutionary changes these machines were bringing. Diebold explained how computers were starting to take over key roles in hospitals and schools. In hospitals, computers were already diagnosing diseases, keeping medical records and managing operations, while schools were using them to add an entirely new dimension to teaching. Diebold also noted how data processing was transforming industries like banking, publishing and retail — ushering in an era of automation.

One of Diebold’s most fascinating predictions was the emergence of what he called the “inquiry industry.” This referred to the idea of central computers storing vast amounts of information, with businesses and individuals able to request data tailored to their specific needs. Diebold envisioned a future where people could sit at terminals in their homes or offices, instantly retrieving information from massive computer networks. He described scenarios like a stockbroker asking for detailed comparisons of company earnings, which would be immediately displayed on a screen — something that feels routine today but was groundbreaking at the time.

Diebold’s vision also included concepts that seem prophetic now: data utilities, or networks of interconnected computers, providing services much like electricity or gas utilities. He suggested that people would rent access to these powerful central computers rather than owning their own machines, a model that anticipated cloud computing. However, he acknowledged challenges, including the high costs of technology and skepticism about its practicality.

By the end of the decade, predictions about computers went even further. Experts saw their potential to help predict economic trends, design complex manufacturing systems, and manage government programs. They also warned that the rapid pace of change would require industries and workers to adapt quickly or risk being left behind. The “technetronic age,” as it was called, promised both unprecedented advancements and significant disruptions.

Below, we’ve gathered a wide range of photos and articles from the 1960s exploring the fascinating developments of this era. This collection offers a glimpse into the predictions, innovations and early uses of computers during this exciting period in history.

What comes next in the computer age: Interview with a leading authority (1967)

US News and World Report – June 26, 1967

Today’s computer revolution is only getting started. In store are amazing new uses for “electronic brains” that will reshape the industry and alter people’s lives.

Coming are computers that will take over a major role in running hospitals and schools. Shoppers will pay by electronic impulse instead of cash. Automation will move from the assembly line to Government policy making.

For a glimpse of what is ahead in this computer age, “US News & World Report” invited to its conference room for this exclusive interview John Diebold, a computer expert who is sometimes called “Mr. Automation.”

John Diebold, 41, is president and chairman of the Diebold Group, Inc., international management consultants. An expert in computers and communications technology,

Mr. Diebold is credited with coining the word “automation,” and has written a basic book on the subject.

His firm includes among its clients some of the biggest corporations in this country and Europe, as well as local, state and national governments.

Interview: The coming computer age (1967)

Q: Mr. Diebold, are computers to bring big changes to our society?

A: Yes, indeed. People don’t realize yet how far-reaching these changes will be, and how their lives are going to be altered by these new machines and new technical developments.

Q: Where? In what ways?

A: Everywhere. Computers in medicine are diagnosing diseases, keeping records, helping run hospitals. Electronic machines in schoolrooms are adding another dimension to teaching.

A revolution in banking and credit and in merchandising is already in progress as a result of data-processing innovations. Publishing, government, the law — all are in ferment because of new technology.

Q: Does this mean many jobs are going to be changed?

A: It certainly does. Many existing businesses are in for drastic shake-ups. But, equally important, we are going to get entirely new industries as a result of breakthroughs in technology.

Q: What kinds of new industries?

A: One brand-new industry is going to be what I’d call the “inquiry industry.” It will make use of the computer’s vast memory ability, its capability for storing and retrieving information.

Today, the dollar value of this computer-based “inquiry industry” is probably less than 20 million dollars. Our studies show it will exceed 2.5 billion dollars by 1975.

Huge central computers will have terminals, or outlets, in business offices and in homes. You’ll be able to request information from the computer and get it back, instantly, in the form you want to use.

ALSO SEE: In the ’60s, computer programmers were in high demand to code in languages like COBOL and FORTRAN

Q: But isn’t that being done in business now — for airline and hotel reservations, for instance?

A: Yes, but it’s going to get bigger and develop into a national industry in which these services are sold, as a business, rather than confined to the internal operations of a single firm.

The important thing is not simply that the computer will provide the information you want, but it will tailor it exactly to your needs.

Q: How?

A: Suppose you’re in a stock-brokerage office and you want to compare the price-earnings ratios of all the major companies in the paper business.

You’d ask the computer to provide that list — maybe rank the companies in order. The answer would come up on a screen on your desk.

Then you’d go a step further and say, “I want to know how Consolidated Paper Company stands among all the companies in the paper industry.”

And the computer would immediately flash on the screen key data about Consolidated Paper.

Q: When will all this happen?

A: It’s already happening in some types of business. You can get an up-to-the-second stock quotation flashed on a screen now. More and more stock-exchange firms are installing these devices.

Q: Is the day coming when a man in his home can dial a code on the telephone and get information on stocks, or weather reports, airline schedules, baseball scores?

A: Yes, though that day is still some way off. It depends mostly on getting costs down and solving some other problems.

Q: When you can get information just by dialing, or pushing a button, will magazines and newspapers become obsolete?

A: I don’t think so. What I visualize is a completely new medium, a combination of video and hard information.

I don’t expect to see the day when “The New York Times” will come pouring out of a TV set. But certain information will be produced by video that will supplement what you read in print.

For example, there’s an editor for one of the London newspapers who does occasional television broadcasts on science. He coordinates that broadcast with what’s on his science page in the evening paper. He treats in the paper, in depth, the kind of material he can’t handle well on the screen.

At the same time, he can use on the screen the heavy pictorial coverage for which he doesn’t have space in the paper. I’d expect to see a lot more of that in the publishing field in days to come.

ALSO SEE: Crazy expensive personal computers from the ’80s, and how their features compare today

Q: Will all these developments change people’s jobs — their traditional ways of doing things?

A: Yes, there’ll have to be changes. You’ve got to look at every job in a completely different way. For instance, a Wall Street firm put in a system for supplying stock quotations instantly to its partners’ desks, just at the touch of a button.

The whole point was you could get any quotation you wanted in an instant. But they found the partners were laboriously copying down on a sheet of paper all the stock prices they were interested in.

The men simply didn’t believe that there was a new, easier way of getting a quotation any time they wanted it.

In earlier days, people would sit back and say, “Let’s wait until the pioneers have finished, then we’ll adopt this new development at a leisurely pace.” You can’t do that in business today. If you don’t innovate, your competitor will — and you’ll be left behind. You can’t afford to wait. Things are moving too fast.

Q: People haven’t grasped the idea that big changes are on the way.

A: That’s right. I don’t think people really believe that things are going to be much different in the future than they have in the past, and there’s resistance to changing.

It’s only when you look backward, after a few years, that you realize how much has happened, how much has been changed.

There’s a story about a British military team trying to cut down on the manpower used in handling a field cannon. Always there had been six men assigned to each cannon, but there were only five jobs.

The team studied each job and went to the instruction manuals. From the first edition of every manual, it called for a crew of six, even though there seemed to be jobs for only five.

Finally, they located the man who had written the manual, a retired General, and asked him what the sixth man was supposed to do, and he replied, “He holds the horses.”

Business today is perpetuating a lot of jobs that magnetic tape and electronic techniques are making obsolete. It’s going to take us time to get used to these new tools.

DON’T MISS: 25 things most people under 25 have never seen in real life (and probably can’t name)

Q: Will competition force changes?

A: Yes. In earlier days, people would sit back and say, “Let’s wait until the pioneers have finished, then we’ll adopt this new development at a leisurely pace.” You can’t do that in business today.

If you don’t innovate, your competitor will — and you’ll be left behind. You can’t afford to wait. Things are moving too fast.

Q: How many computers are there in the U.S. today?

A: About 40,000.

Q: Will that number go up sharply in the next 10 years?

A: It will increase substantially. One of our studies shows that annual outlays for computers in the next few years will be about 10 percent of the total expenditures for plant and equipment.

But, even more important, computers will get larger and more versatile, so it won’t be necessary for everyone to own a computer. You’ll just rent a terminal and plug in to the central station.

Q: A sort of “data utility”?

A: It could be, in much the same way that we have local and regional electric utilities or gas utilities. To help hold down communications costs, we may very likely have local or regional computer utilities that serve a particular city or a region. These local data utilities, in turn, would be interconnected with other regional systems in a big nationwide network.

Q: All to be regulated by the Government?

A: The Federal Communications Commission is studying that question now.

Personally, I think regulation of data handled by private computers would be a great mistake. Every company that operates nationally or regionally today is starting to have substantial amounts of data communication.

MORE: 30 retro-futuristic space-age inventions we’re still waiting for

If you’re going to try to regulate this sort of business activity — other than the regulation already applied to the telephone companies and other communications agents — you’re going to run into a real mare’s nest.

Suppose you have six or seven computers in one company with terminals all over the organization, and coded data being fired back and forth across the country, or around the world — how on earth do you regulate all that? I don’t see how it can be done, nor do I see the desirability of it.

Science & space: Where the brains are (1968)

From Newsweek – January 29, 1968

In the past, such traditional indicators as population, natural resources, gross national product, balance of payments and military might have been used to measure national power.

Now, however, economists discern a new yardstick: computer power. And it may well be that the US has such a commanding lead in the development, construction and programming of machines to do its brain- and paper-work that other industrial countries will never catch up.

“There is no doubt,” says Charles Reed of the State Department’s office of international scientific and technological affairs, “that American superiority in computers plays a central part in the Europeans’ concern with what they call the technology gap.”

Other observers have also noted how quickly computers have pervaded American society.

MORE: Vintage copy machines: See the kinds of old photocopiers that offices used to have

Princeton’s president Robert F Goheen thinks their impact can be compared to Gutenberg’s invention of movable type.

And Zbigniew Brzezinski, professor of political science at Columbia University, has even introduced the phrase “technetronic” society to describe a country “shaped culturally, psychologically, socially and economically by the impact of technology and electronics.”

In the US, the technetronic age has begun to take shape. Some 39,500 computers — about 65 percent of the world’s total (chart) — have already begun to reach into every facet of life.

The whirring, humming machines solve problems too complex for human mathematicians, help economists make policy decisions and may even revolutionize the classroom. Soon computers will be selling tickets to concerts, plays and baseball games.

Some day, they may be programmed to run most industrial and manufacturing plants. Prodigious memories and fast calculating speeds give computers their power.

For instance, an IBM 360-91 unveiled at the Goddard Space Flight Center last week can do in a single minute calculations that would take a human mathematician 4,000 years to do by hand (with a desk calculator, the job would take “only” 100 years).

The computer’s main assignment will be to keep track of satellites.

Prediction

While the US long has employed computers in military and space operations, Washington now increasingly uses some of the 3,000 Federal computers to help avert domestic crises.

At the Department of Commerce, for instance, a computer helps economists predict how the economy will behave during the coming year.

Programmed with a model of the US economy, the computer shows how changes in investment, tax rate, consumer purchasing power or other factors affect economic health.

ALSO SEE: 50+ sexist vintage ads so bad, you almost won’t believe they were real

How will the technetronic age change the US?

Brzezinski sees two major consequences. First, he predicts explosive progress in the sciences and therefore in other fields.

Once computers and automation have freed man from having to spend most of his time working, Brzezinski believes that society will seek out and cultivate human intelligence for scientific, medical and other careers.

And what will the rest of the population do? “The achievement-oriented society,” says Brzezinski, “might give way to the amusement-focused society.”

Old age

Another challenge comes from computers themselves. The tape and ferrite-core memories of computers and their banks of lightning-quick circuitry challenge even the ingenuity of their own inventors.

“Our problem,” says one technician, “is describing what we want from the computer. The computer’s capability has far outstripped our ability to use it.”

Most of the problems and challenges of the technetronic age now stop at the shores of the US Europe and Japan, by all (human) calculations, are still back in the old industrial age.

The US, for instance, has more than ten times the computer capacity of West Germany, the next biggest computer user. Furthermore, most of the computers operating were made by US firms.

Realizing how badly they lag, other countries have begun to make a determined effort to catch up. France, for instance, has launched an ambitious program — the plan calcul — aimed at developing an independent national computer capacity.

Two factors precipitated the decision: the threat of control implicit in General Electric’s acquisition of one-half interest in Machines Bull, the largest independent French computer company, and the US refusal for two years to sell France the computers needed for the creation of the force de frappe.

In Britain, progress has been substantial. There are now more than twice as many computers on line as there were two years ago.

Furthermore, the British Government has spent $36 million in the last few years on computer design and application. The biggest obstacle, however, seems to be the innate conservatism of British businessmen.

Even in Germany, US firms control almost 90 percent of the market, a fact that worries Bonn.

“Please note we have no ‘buy German’ act in this country,” science minister Gerhard Stoltenberg once told IBM’s Thomas J Watson Jr, “but we have to do something for the computer industry to keep from becoming an underdeveloped country.”

That something is usually subsidies, and pressure to use domestic machines.

The German computer industry has responded well. Instead of competing directly, German firms are now exploiting narrow slices of the market, like machine control, where US competition is not as strong.

Richer rich

For all Russia’s concern with technological progress, her use of computers has not been impressive.

“Russia,” says the State Department’s Reed, “is behind the US in computer technology. They produce fewer, less sophisticated machines, and there is not as much nongovernmental use in Russia, as in the US.”

Also Russia’s highly-centralized economy may be too complex even for a computer. One expert, Viktor Glushkov, wryly claims that all the central planning problems for one year would take more than a year to solve with a million computers making 30 thousand calculations a second.

In Japan, US manufacturers have dominated the computer market through licensing agreements with local firms. The Fujitsu company, however, has taken part of the computer field without relying on US help.

Consequently, it is the only Japanese firm not restricted by US licensing agreements from selling its machines abroad.

A major reason for the gap, of course, is the tremendous cost of developing and producing computer systems. And even in this area, the rich are likely to get richer while the poor get poorer.

The US Government’s investment in computers has streamlined operations and produced savings measured in the millions each year. This frees funds that can be plowed back into still more computer power.

Meet IBM’s STRETCH at Los Alamos (1961)

STRETCH, the most powerful computer yet built, which was delivered in April by the Poughkeepsie Laboratories of International Business Machines Corp. to the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory of the Atomic Energy Commission in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

The computer will be used for research and development in nuclear and thermonuclear energy.

The machine contains 6 magnetic core memory units which will store more than I14 million decimal digits, with access in approximately 2 microseconds.

Working with fourteen-digit numbers, the machine can add in 1.5 microseconds, multiply in 2.7 micro-seconds, and divide in about 10 microseconds.

PACE TR-48 fully transistorized general-purpose analog computer (1961)

Why Jeep chose the NCR 315 Computer (1964)

Kaiser Jeep Corporation, Toledo, Ohio: World’s largest manufacturer of 4-wheel drive vehicles

Early in 1960, we began an extensive analysis of computers, and assigned a value to each factor used to evaluate the many systems on the market.

After all research was completed and we had totaled the score, the NCR 315 Computer was found to be the one best suited to our particular needs. Specifically, our evaluation was based upon many factors.

To name a few — technical equipment comparisons, operating efficiency, installation and site preparation requirements, software, ability to expand the system, etc.

Today, we have daily working proof that ours was a sound and profitable choice. Our EDP installation is costing us less each month in rental charges than our previous system, yet the NCR 315 is accomplishing the data processing on each application much faster and more accurately than previously possible.

ALSO SEE: See vintage Jeep Cherokees, from their debut in the ’60s through the ’80s

Retro computer components: Building blocks for tomorrow’s telephone service (1965)

Thousands of tiny components like these make up a brand-new, highly complex communications system known as the Electronic Switching System, or ESS.

Over the next few years, millions of American telephone users will benefit from the new service it promises. But at Western Electric the coming of electronic switching presents a technical challenge equal to any we have faced in the 83 years we have been a member of the Bell System.

Equipment for a typical ESS switching center, for example, requires some 160,000 tiny diodes, 55,000 transistors, 26,000 transformers, 226,000 resistors, capacitors and similar components.

Western Electric people must produce these electronic components to unprecedented quality standards — and do it economically.

Then each of the thousands of precision parts must be assembled so that they work perfectly, each with each, and with every other of the billions of components that make up the nationwide Bell System communications network.

This can happen only because Western Electric people, as members of the Bell System, share in its goals. Together with people at Bell Laboratories, where ESS was developed, we strive for the perfection that enables your Bell telephone company to bring you the world’s best communications service.

ALSO SEE: The history of the telephone, with 50 examples of old phones, including early rotary-dial models

The Informer (1967)

The Informer. That’s what police chiefs call the NCR 500 computer system.

Because that’s what it does. Informs. About the time and place crimes are most likely to occur. About criminal activity by type and location and suspect identification.

Now police are capable of faster response to your calls. Law enforcement personnel can be more effectively deployed exactly when and where required to prevent crime and control traffic. Your tax dollar works more efficiently, more effectively for you.

This is just another NCR way to help solve problems. The men who created this NCR 500 also build computer systems to help you in your business.

A science-fiction buff with straight”A” in math… now Blair Tyson plots a course to the moon. (1967)

From simple addition to analytical geometry, math was a snap for Blair Tyson. He was not only a whiz kid at mathematics, but he had an absorbing interest in any and all types of science fiction.

Graduating from the Milwaukee School of Engineering in 1958, Blair began working with computers for an electronics company.

Here is where his background in science fiction and his aptitude for mathematics merged and were given direction. This combination of interests led him one way… to the AC Electronics Division of General Motors in Milwaukee.

Now he works on airborne digital computers. It is AC’s job to integrate these computers into the guidance systems for space project Apollo. The goal is the moon, and GM’s Blair Tyson helps chart the way.

SEE MORE: To the moon! 20 newspaper headlines from the Apollo 11 launch on July 16, 1969

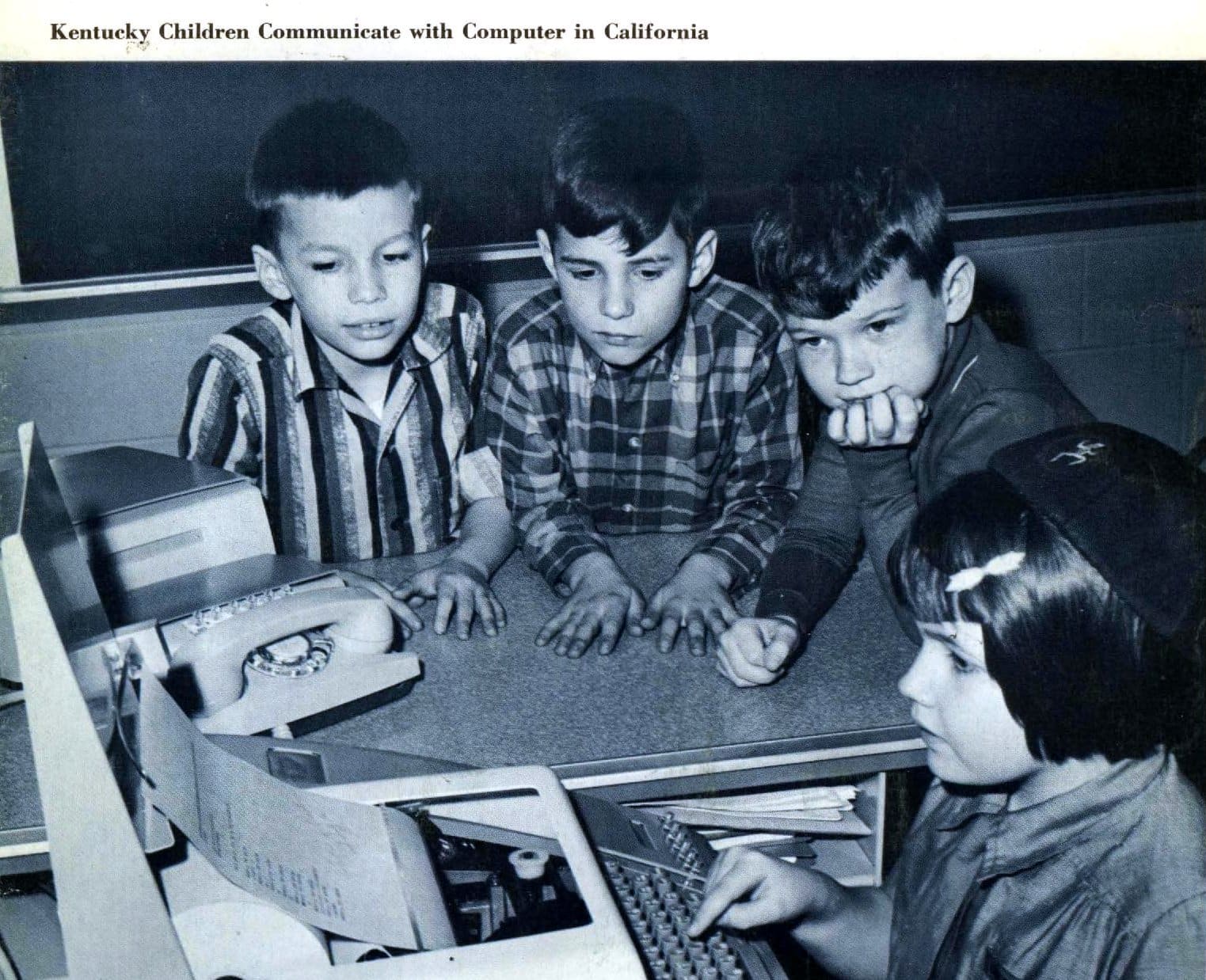

Kids in Kentucky in 1967 learning how to use computers

Honeywell computers to typeset the Boston Globe newspaper (1967)

NEWSPAPERMEN GO TO PRESS FASTER, more accurately, aided by a new Honeywell automation system.

Keyboard operators type news and classified advertising copy directly into a Honeywell computer, which operates typesetting machines. It automatically provides correct spacing, hyphenates words where needed, and speeds the typesetting process.

Both newspapers and readers benefit. Automation helps newspapers to continue to provide in-depth coverage of today’s fast-breaking news events, to meet tight deadlines while delivering more papers than ever before.

Printing is one of the many areas where… Honeywell automation systems help make people more productive.

DON’T MISS: See some of the first laptop computers: Clunky, slow & expensive tech everyone wanted

Computers in the 1960s: NCR Century Series business computers (March 1968)

Announcing the world’s most advanced new family of computers. The NCR Century Series. Never before so much performance at so low a cost.

NCR introduces the Century Series. This new computer family will change all your old ideas about computer costs and capabilities.

New technological innovations make possible outstanding price/performance. Ultra-fast 800 nanosecond thin film, short rod memory. Monolithic integrated circuitry. High-speed dual spindle disc units.

Memory sizes from 16,384 to 524,288 eight-bit characters. Sophisticated operating software. NEAT/3, COBOL, FORTRAN. Line printing speeds from 450 to 3000 LPM. Real-time processing and multi-programming.

And best of all, true upward compatibility. No reprogramming as you move upward in size.

What does it all mean to you? Tremendous cost and time-saving, to name just two benefits. To learn at least ten others, contact an NCR man. He’ll give you the story of the Century.

ALSO SEE: The personal computer revolution: See how people in the ’70s predicted home PCs would be used

The computer communications robot display from GTE (1969)

If you’ve ever made a phone call, followed a satellite, watched color TV (or black & white, for that matter), turned on a light, taken a flash picture, gotten an instant stock quotation…

If you’ve ever sent an electro-cardiogram by phone, seen the San Diego Chargers win a night game, listened to Rock on Stereo or Bach on FM, then you’re acquainted with our versatile friend on the left.

A man of many parts, you’d have to say. Over 20,000 when last counted. All supplied by us. General Telephone & Electronics [GTE].

We put him together to show you the many ways we’re involved in the many ways people communicate with other people. When it’s by telephone, we’re involved in 34 states. (We’re also involved in making much of the equipment used in making telephone calls.)

When people communicate by electronics, our Sylvania people are very much involved. In color television, tape recorders, radio, stereo.

Satellite tracking systems, too, and lots of other sophisticated communications stuff. (The same Sylvania so big in flashcubes, and in home and industrial lighting.)

As for our friend on the left, he’ll soon be pretty involved himself. Starring on television on the CBS-TV Playhouse, come October 7. Watch him turn on. All 23 feet 6 inches of him.

NOW SEE THIS: In the ’60s, computer programmers were in high demand to code in languages like COBOL and FORTRAN