Meet Little Stevie Wonder, age 13 (1963)

Young blind jazz musician gets start with harmonica

Zanesville Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio) October 19, 1963

Behind the unseeing eyes of Little Stevie Wonder, there is music and rhythm. As he sits and talks, his hands beat jazz rhythm on imaginary bongos. It seems as if he is giving a beat to a tune playing in his mind. Almost every waking hour of the 13-year-old recording sensation concerns his music.

Because Stevie cannot see, the world of sound is much more important to him. “I started loving music almost as early as I can remember anything,” he told us. “The thing I want most to do is to make people happy. If my music makes people happy, then I’m happy.”

Stevie was doing a personal appearance date in a New York theater. And, he was making people happy. He received top billing over many well-known stars. At 8 in the morning, over 1,000 under-20s were lining up to get tickets for the 10:30 show. Each show played to a packed house.

The slightly-built 13-year-old boy was almost an overnight sensation. His first really big success came with his recording of “Fingertips.” The single moved so fast that Tamla Records rushed out the “Twelve Year Old Genius” album. The result: Stevie, a few weeks ago, held the unique distinction of having both his single and his album listed as the top sellers in the country.

Stevie, blind since birth, took his first musical step when he was four years old by buying a 10-cent harmonica. He soon mastered the instrument. A few years later, he inherited a piano from a family moving out of the neighborhood. He began to play it almost immediately. He then added the organ, the bongos and the drums to his list of instruments. He was also blessed with a fine singing voice.

In his native Detroit, he became a familiar sight. He refused to pamper himself or be pampered, so Stevie walked the streets by himself playing the harmonica (his favorite instrument) and doing a graceful soft shoe routine.

One of his buddies in Detroit was Gerald White, brother of Ronnie White, a member of the famed vocal group “The Miracles.” Ronnie heard Stevie sing, and brought him to Tamla Records for an audition. Tamla officials flipped over Stevie’s talent and versatility and immediately signed him to a recording contract.

The rest is recording history — the fans snapped up his records and flocked to see him in person.

“One of the things that makes me very happy is that my friends around the country write me. I get about 100 letters a day from kids,” Stevie said. “I receive so many gifts I hardly know what to do with them except to feel thankful for the friendship of those who send them. I’ve got a lot to be thankful for.”

Stevie is an affectionate, friendly boy who loves to talk to people. This accounts for his favorite “toy.” It is a walkie-talkie set which lets him talk to people almost any time he wishes.

He started a traffic jam in New York when he let some of his fans take one of the walkie-talkies down the block and carry on a conversation with him. Hundreds of kids jammed around the set to take their turn talking to the popular singer. Soon the corner turned into a mob scene.

Major television dates are in the offing for the little genius this fall. Following an extensive national tour, he will travel to Europe. When he’s home he attends school, but on the road he has a private tutor. “He’s a good, bright student,” she reports.

Stevie said he likes to make people happy. Actually, he does more than say it. Today in Detroit, a beautiful, new home is under construction for his parents. “Boy Wonder” may sound too much like a publicity man’s term, but those who have met him have their own phrase — “wonderful boy.”

Meet big Stevie Wonder (1969)

By Craig Modderno – Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California) March 2, 1969

Moving onstage to the Motown beat of his hit songs “Uptight” and “I Was Made to Love Her,” the 18-year-old musician in the dark glasses performs with a rare, vibrant enthusiasm.

When the show ends, the “Prince of Soul” is escorted offstage by the guiding hand of his musical conductor. Blind since birth, Stevie Wonder is a part of many different worlds.

In his dressing room at Mr D’s, Stevie drank tea and talked about his career. “I’ve been recording for eight years, but I dreamed of my name in lights before I ever thought I would be a success. I consider my talent to be a gift of God, and I’m very thankful for it.”

In 1963, Little Stevie Wonder recorded a live song that was entitled “Fingertips.” Though, the lyrics were simple, Stevie’s exciting vocal performance made it the No 1 record of the year.

Video: Stevie Wonder Uptight!/A Place In the Sun (1966)

Performing on the from Mike Douglas show

What happened to Little Stevie Wonder?

What happened to Little Stevie Wonder? “Well, he grew up. He got taller,” said Stevie with a smile. His material now includes tunes like Bob Dylan’s “Blowing In The Wind,” which he recorded after attending a Dylan concert and “feeling the atmosphere the song created within the audience.”

Stevie plays drums, organ and harmonica, an instrument which he plays a beautiful rendition of “Alfie.” When he records a single release, he plays all the percussion instruments and later dubs in the chorus.

Discussing musicians, he spoke in awe of the talents of Jose Feliciano. “He’s fantastic. I don’t see how anyone blind can play that well.”

Wonder’s blindness doesn’t handicap him from reading books, writing songs, and musical arranging. “When you write a song you leave something of yourself behind. I like the arranging of ‘For Once In My Life’ because it’s great to take a good song and give your personal feeling to it.”

Three female fans came in to talk with Stevie, and he began to feel at ease. They discussed astrological signs and the traits of people born under each sign.

Since Stevie is a Taurus, the bull, one girl said that he is a little egotistical, but Stevie happily proclaimed that this fault was a sign of his strength. Asked what sign I was born under, I replied “a Budweiser sign,” although Stevie later guessed me to be Aquarius.

A teen with new ideas & deep concerns

Despite his musical success, Stevie is basically a teenager with deep concerns and new ideas.

“Older people don’t accept younger people. The older people are afraid to be a part of any change, while many young people just don’t have anything to express. The only way to get anything done is for both sides to try to communicate,” Stevie said eagerly.

Expressing an admiration for the late Dr Martin Luther King, Stevie rejected the preachings of violence. “I can’t accept anyone who preaches hatred. Musicians generally aren’t violent, and I’m certainly not. The young white people are now beginning to see what being real is, and I feel the races are getting very close together.”

Stevie started tapping a melody on the table and teasing the girls. Whenever someone told a funny joke, he held out his hands for them to slap. He signed an autograph, but had to have his hand guided by another person. Whether it’s an audience or a group of happy fans, Stevie needs to “touch what my heart used to dream of.”

“Meeting and communicating with people keeps me grooving,” Stevie said, and he started snapping his fingers while getting ready for his show.

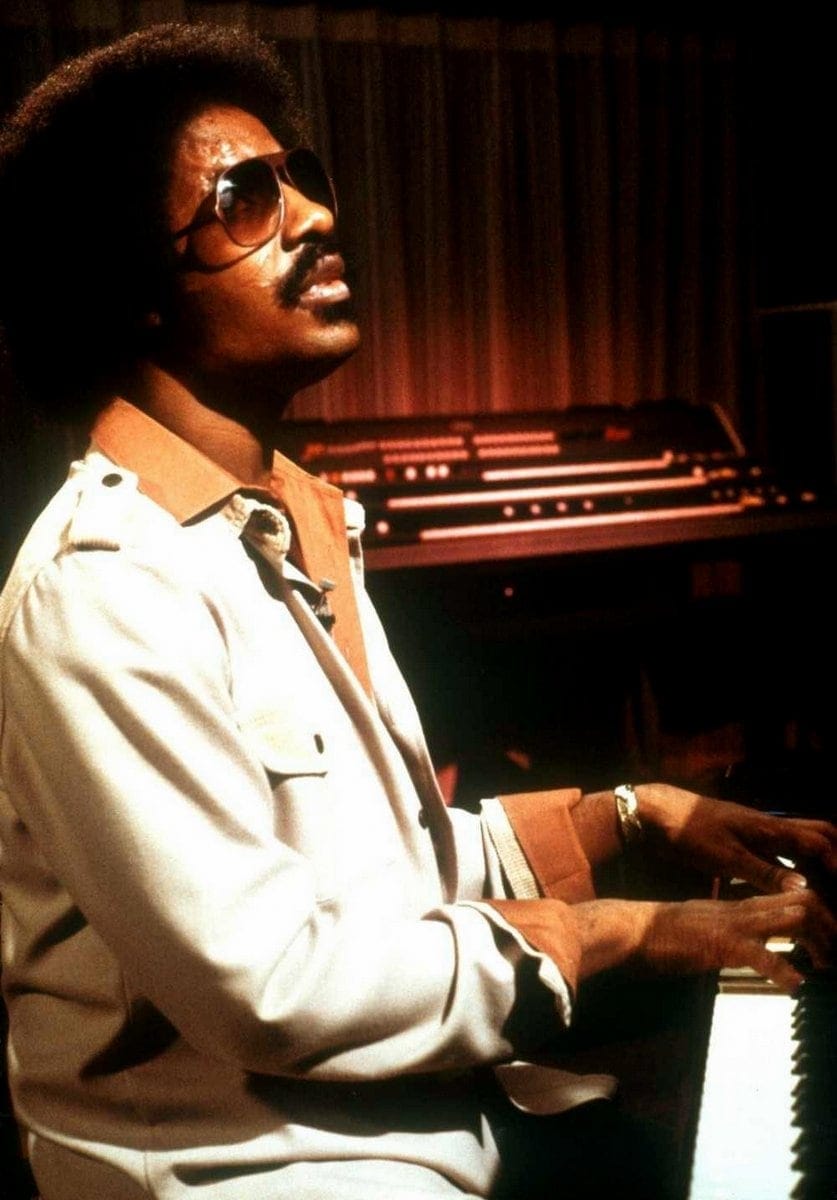

Stevie Wonder: The genius of the man and his music (1977)

Excerpted from an article by Jack Slater – Ebony, January 1977

Not surprisingly, he turns out to be as complex as his music — passionate, earthy, spiritual, romantic, authoritative and, above all, intensely religious — at least, at this juncture in his life.

“I think,” he says, “that the synthesis of thought in my music comes not from myself, Steveland Morris, but from a deity called the Supreme Being or Allah or God. I appreciate the honor of the Supreme Being making me His vehicle.”

It seems an unusual statement for a pop musician to make, but coming from Stevie Wonder’s lips. it is entirely consistent with the complexity, a complexity that shatters any attempt to reduce Stevie Wonder to a stereotype.

WHEN he was a very young boy in Detroit, his mother, with her friends, used to take him to various faith healers to “cure” his blindness. The preachers, who were “empowered by God,” would chant over him, pray over him and then, instilling in him the confidence to see, seize his shoulders or touch his eyes so that the power of the Lord could flow through their hands to him.

Congenital blindness was a disease, an affliction, so it seemed, which could not be merely adjusted to, or accepted, but must be eliminated once and for all.

Fortunately, Stevie never wedded himself to the “disease” point of view, and he has never, he says, viewed his blindness as an affliction that cruelly deprives him of the wonderful world of vision. Yet it might so easily have been otherwise.

Born Steveland Judkins in Saginaw, Mich., on May 13, 1950, he was the third in a rather poor family of six children who had different fathers. Shortly after Stevie’s birth, his mother moved her family to Detroit, where Stevie grew up as Steveland Morris and began attending elementary school.

Being black, blind and from Detroit “projects,” Steveland Morris might have, at best, ended up making brooms and selling pencils—and, at worst, might have spent his life haunting some street corners with a seeing-eye dog.

Fortunately, he was forced into none of those pursuits. At home or on the school bus — whenever he could — he listened to a black radio program called “Sundown,” and he became mesmerized by the then relatively new rhythm and blues, particularly the blues as B. B. King would sing it. Noticing that the boy liked music, a barber gave him a harmonica. Later, Stevie, singing, took to the piano and the organ, then to the drums and the bongos.

WHEN he was 11 years old, his knight in shining armor came in the form of Ronnie White of the Miracles. Having heard of the boy through a younger brother who was a friend of Stevie’s cousin, White listened to the lad’s music, liked what he heard, and took him to the local black recording company, Hitsville U.S.A.

The company’s president, Berry Gordy Jr., impressed by the boy’s voice and his adeptness with various instruments, signed him to a contract and changed his name to something more marketable, more showbiz, and at the same time more descriptive of the prodigy he, Gordy, recognized.

Two years later, when the Wonder boy was 13, Hitsville’s “12-Year-Old Genius” recorded a single called Fingertips. It sold 1.6 million copies and became one of several less-than-memorable tunes that helped establish both Stevie and his fledgling employer.

Later, Gordy made another name change: Hitsville became Motown; and, for many years thereafter, Motown and Little Stevie Wonder were nearly synonymous.

“But that was a long time ago,” Stevie once said. “Like, I was growing up, you know.” He reached manhood, then, as an appendage of Motown.

Becoming his Great Black Father, the recording company served as his legal guardian, oversaw his education, booked his concerts, employed a tutor for him with the “right” values and, most important, reinforced in him the fiercely defensive puritanism inherited by most black people who are a part of, or on their way up from, the working class.

Referring to the $2.50 weekly allowance Stevie received from Motown when he was 13, his tutor, Mrs. Ardena Johnston, told EBONY in July 1963: “Sometimes he spends it all, and then he whispers in my ear, ‘I’m broke.’ I whisper back, ‘I’m broke, too.’ We hope to teach him to use his money wisely, to avoid champagne tastes.”

Later enrolled at the Michigan School for the Blind in Lansing, Stevie had another tutor when he was on the road for Motown. “I toured mostly on weekends and sometimes a couple of weeks a month,” he says of that happy period of his life.

DURING the 1960s, he was singing such songs as Uptight, I Was Made to Love Her, For Once in My Life and Signed, Sealed and Delivered — most of them very popular, very bubbly, romantic potboilers that he and others at Motown wrote by the dozens.

As he became older, the romantic fluff he wrote and sang became less interesting to him, less rewarding emotionally, and he began to reevaluate his relationship to it and to Motown. The album entitled Where I’m Coming From may have been Stevie’s oblique way of telling the executives at Motown what they did not want to hear. It was his last recording effort under the old arrangement.

In 1971, when his second five-year contract came up for renewal, Stevie, then 21, told Motown he wanted out.

“They were upset at first,” he recalled. “But they began to understand — later. Whatever peak I had reached doing that kind of music, I had reached. It was important for them to understand we were going nowhere.”

With his lawyer, Johanan Vigoda, Stevie negotiated an unprecedented contract with Motown whereby the corporation would distribute his records and he would get, in addition to complete artistic control, his own production company and a considerably higher proportion (50 percent, according to Ira Tucker Jr., Stevie’s press liaison) of the royalties.

On his 21st birthday, he was eligible to assume control of the $1 million which had accumulated for him in trust over the years. So after selling an estimated 35 million records, after coming up consistently with one standard hit after the other for less than 10 years, Little Stevie Wonder, who had already shed part of his name, decided to become a musician.

Later, he found the technical direction he wanted his music to take in the Arp and Moog synthesizers, machines that can electronically produce almost any sound desired. Stevie’s earlier songs had used traditional instrumentation, mostly to achieve a certain emotional effect. But his new compositions (Superstition, Higher Ground and Living for the City, among them) now took on a more “mental” flavor, as well as a rock sound, resulting directly from his use of the synthesizers.

He didn’t sacrifice the emotional content of his music, but the Arp and Moog did offer him the dimension he wanted. “They express,” he has often said, “what’s inside my mind.”

Since “Where I’m Coming From,” Stevie’s albums have become increasingly mental, increasingly social and more spiritual in tone, a tone which is particularly evident in Songs in the Key of Life.

And he succeeds in achieving that tone without ever becoming pious or academic or stilted; for much of his music is firmly rooted in a joyous gospel-like beat that often embraces lyrics of incredible beauty. If Stevie Wonder is a musician of considerable power, he is also a poet of considerable passion.