Before all that, she was just a teenager from Brooklyn with a good report card, no money, and a habit of staging mock auditions in the bathroom mirror.

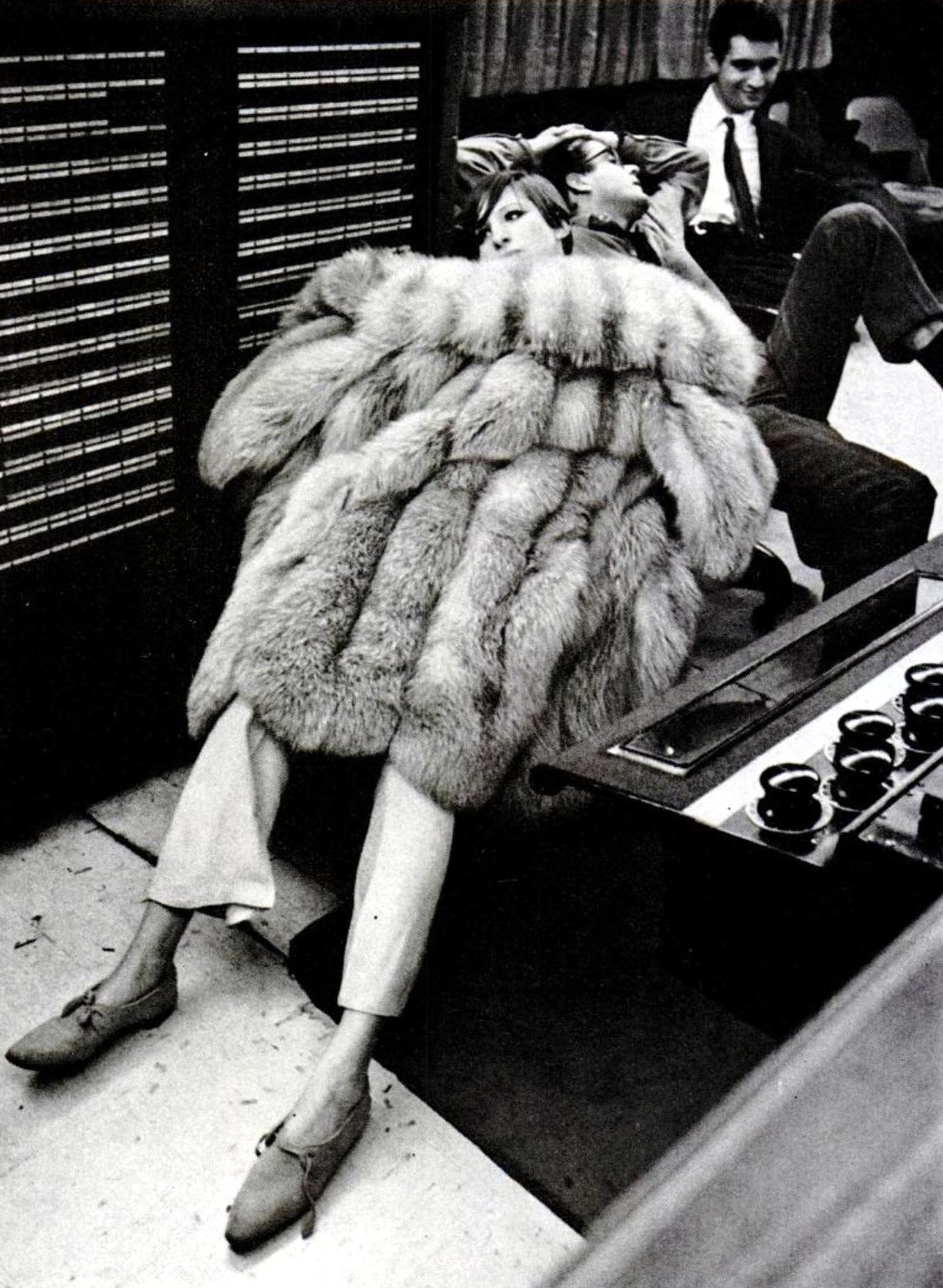

She started performing in small clubs in the Village, usually wearing something she’d pulled from a thrift store. Her clothes didn’t match, her eyeliner was heavy, and she didn’t seem interested in softening her features for anyone else’s comfort. That approach — not hiding and being entirely true to herself — stayed with her, even as the stages got bigger.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif, Kay Medford (Actors)

- William Wyler (Director) - Ray Stark (Producer)

Her first real break came in 1962, with a supporting role in the Broadway musical I Can Get It for You Wholesale. The part wasn’t large, but she stole the show anyway. Not long after, the record contracts started coming in, and so did the television spots. By the time Funny Girl premiered, Streisand already had a few best-selling albums under her belt — and a growing fan base made up of people who didn’t see themselves reflected in typical showbiz stars.

The press didn’t always know what to make of her. Some profiles fixated on her looks, comparing her to animals or fictional characters. But they also recognized that something real was happening. Streisand’s timing, phrasing and vocal control made her a standout. Onstage, everything was sharp and confident. Offstage, she often came across as a little awkward, unsure and still adjusting to the spotlight.

That gap between the private person and the public image was part of her appeal. She wasn’t polished in the way entertainers were expected to be, but she was professional. She was late a lot during her early stage run, but by Funny Girl, she understood the stakes. Being the lead in a Broadway production was a weighty responsibility, and she took it seriously. She also took fame seriously for the same reason; she understood the responsibility that came with it. She also knew how fast things could change.

Below, we’ve collected some articles and photos from those early years, when Barbra Streisand’s star was rising fast and reshaping the expectations for what a leading lady could be. It’s a look at the time before she became iconic — when she was still being called eccentric, strange or surprising — and when none of that stopped her.

Barbra Streisand at 21: A born loser’s success and precarious love (1964)

By Shana Alexander, Life (May 22, 1964)

It is possible to divvy up humanity a lot of ways — rich and poor, black and white, young and old. Another way is winners and losers, and seen from this angle Barbra Streisand started from about as far back as one can get.

When, five years ago, 16-year-old Barbra decided to leave Flatbush, invade Broadway and aim for the stars, she had every mark of a loser. She was homely, kooky, friendless, scared and broke.

She had a big nose, skinny legs, no boyfriends, a conviction that she was about to die from a mysterious disease, no place to sleep but a portable folding cot and, worst of all, a super-sensitive brain which could exquisitely comprehend precisely how much of a loser she actually was.

Things being how they were, there was only one possible way out for Barbra: straight through the top of the tent.

Funny Girl is the proof that she made it. When Barbra opened on Broadway as the star of the new musical comedy last March, the entire, gorgeous, rattletrap show-business Establishment blew sky high. Overnight critics began raving, photographers flipping, flacks yakking and columnists flocking. Thanks to such massive stimulation the American public has now worked itself into a perfect star-is-born swivet.

Today Barbra Streisand is the drummer boy leading the charge. Cinderella at the ball, every hopeless kid’s hopeless dream come true. Having effectively routed the winners, that puny minority of beautiful girls and successful men, she now stands as the fervent heroine of Everybody Else. Her show is a sellout and her albums are a smash.

Even more remarkable is the sudden nationwide frenzy to achieve the Streisand “look.” Hairdressers are being besieged with requests for Streisand wigs (Beatle, but kempt).

Women’s magazines are hastily assembling features on the Streisand fashion (threadbare) and the Streisand eye make-up (proto-Cleopatra). And it may be only a matter of time before plastic surgeons begin getting requests for the Streisand nose (long, Semitic and — most of all — like Everest, There).

Like the nose, the girl is unique. For one thing, she reverberates between extremes. She appears to be at once both beautiful and ugly, rough and smooth. graceful and awkward, childlike and of immense age.

In the recent journalistic frenzy to commit Barbra’s appearance to paper, she has been likened to an amiable anteater, an ancient oracle, a furious hamster and an elegant Babylonian queen. At varying moments she resembles them all.

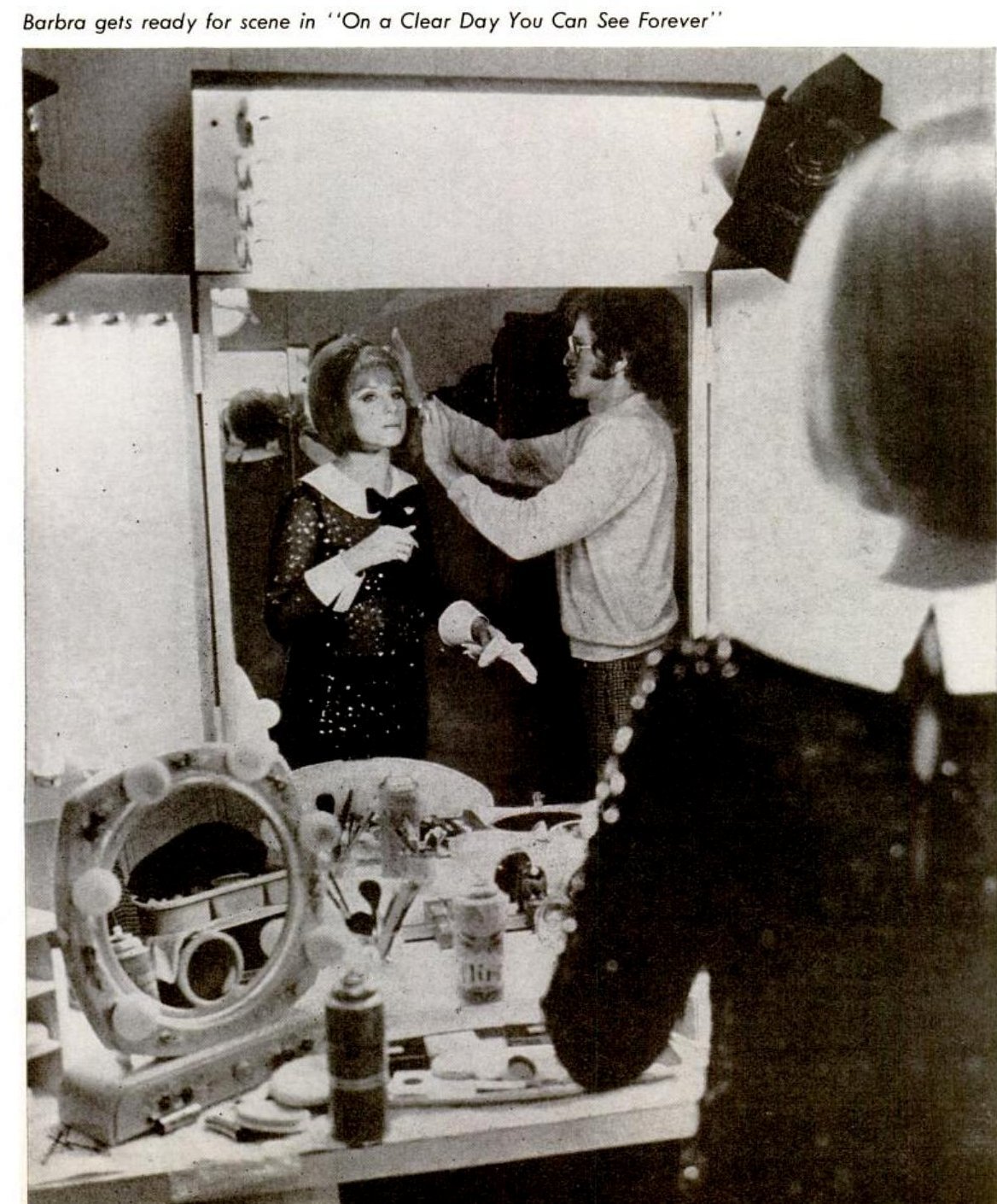

But the surprising, stunning supertruth is that there are times when she does become incredibly beautiful. Stand beside her at her dressing-room mirror backstage, so that you can see simultaneously both the real girl and the reflection in the glass, and the truth about her weird, now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t beauty comes clear: a furious Flatbush hamster stares into the mirror, but it is the Babylonian queen, haloed in lightbulbs, who gazes regally back. “I AM GORGEOUS!” she insists. And she is.

But Barbra’s talent is no illusion. Her artistry is inborn, and enormous. She has tone, taste. elegance of line, and a sense of what is “right” for Barbra that is close to being flawless.

On stage, everything about her is avocado smooth: her voice, her gleaming copper helmet of hair, her gliding motions, the long, slow fullness of her body movements. Off stage she is appealing for opposite reasons: she is rough, timid, unformed. For, of course, Streisand is not just a huge dollop of talent. She is also a 22-year-old girl, a young bride, and very vulnerable indeed.

The great magnitude of Barbra’s talent was apparent in chrysalis form the first time she sang on any stage professionally four years ago, in a Greenwich Village nightclub. “This girl had to become a great star. Anybody could see it,” observers of the historic occasion have since maintained.

Anybody could see, too, that this girl was already a five-star eccentric. For her debut, she wore a $4 dress salvaged from a thrift shop, a frayed Persian vest, clown-white make-up, an English sheep dog coiffure, outsize Minnie Mouse shoe buckles, and the song she chose to sing was “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?” But eccentricity could not disguise her talent.

Eventually she was signed to do two specialty numbers in the musical comedy, I Can Get It for You Wholesale. One number, “Miss Marmelstein,” stopped the show. Records, TV and nightclub work followed in furious profusion and, by the time Funny Girl opened, Barbra was already the top female LP seller in the country.

In all, dozens of agents, managers, teachers and taste-makers played minor roles in bringing Barbra Streisand to her present boiling point, for in reality there is no such thing as an Instant Star.

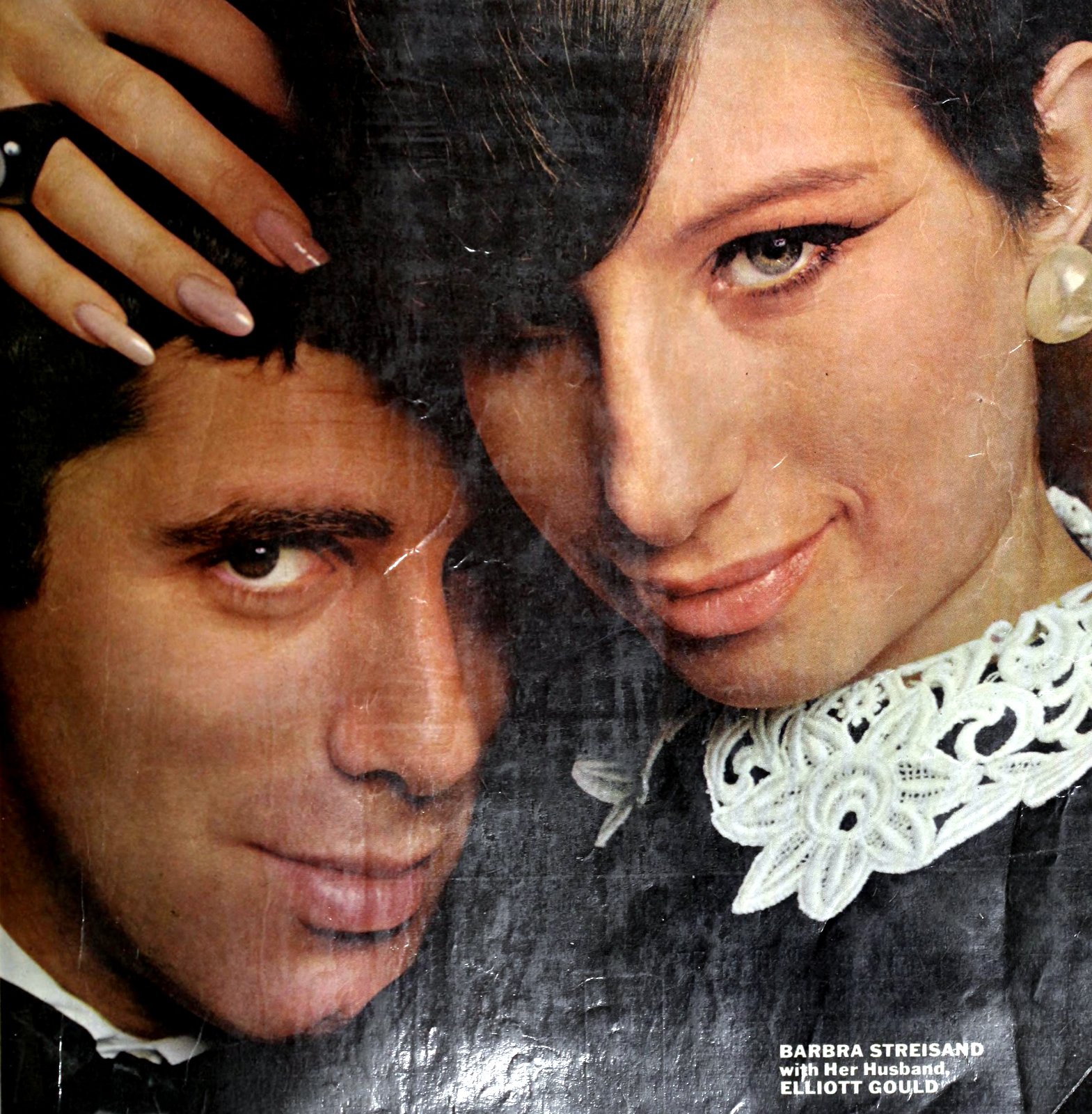

Stars are made, not born. But the one person who really stirred up the marvelous, original concoction which is Barbra Streisand today, who not only homogenized the raw talent and the growing girl, but who a thousand times has saved the whole brew from dribbling away into a vain splatter of nerves and doubts, is Barbra’s young husband, a wry, mop-headed, accomplished singer-dancer-actor named Elliott Gould.

The private story of Mr and Mrs Gould is less sure-footed but oddly more comprehensible than the public success story of Barbra Streisand. It is a precarious love story. But unlike the old-fashioned romance between Fanny Brice and her gamblin’-man husband which forms the creaky plot of Funny Girl, the Goulds story is as con-temporary as a TV dinner.

It began at the auditions for I Can Get It for You Wholesale. Elliott had just been cast as the leading man when Barbra suddenly materialized, like some Halloween spook, as Miss Marmelstein.

Elliott was 23, Barbra was 19. Each was on the brink of stardom. Offstage, each was painfully shy. Buffeted by incipient success, they became inseparable.

Says Barbra, “We worked together, we lived together, we were not apart for more than one hour. We thought of each other as Hansel and Gretel.” But Barbra has her fables garbled. The real prototype for Barbra Streisand is the Ugly Duckling. Elliott was the first person who saw the swan.

“A freak — a fantastic freak!” Elliott remembers thinking. He was slouched in the darkened theater watching the Marmelstein auditions when, over the footlights, clambered a strange-looking, skinny creature with long, spiky hair, spidery hands, two-inch nails and purple lipstick.

“I sang,” Barbra recalls, “and then I sort of ran around the stage yelling my phone number and saying ‘Wow! Will somebody call me, please! Even if I don’t get the part, just call!’ I’d gotten my first phone that day, and I was wild to get calls on it.”

That night Elliott phoned her. “You said you wanted to get calls, so I called,” he said. “You were brilliant.” Then he hung up.

They did not meet again until the first day of rehearsals. “Barbra had this satchel bag and tattered coat. She looked like a young Fagin,” Elliott remembers.

“I thought he was funny looking,” says Barbra. “He gave me a cigar. He was like a little kid. One day at rehearsals I saw the back of his neck and — I just liked him.”

Elliott was too shy to ask for a date, but he started walking Barbra to the subway after rehearsals.

“She scared me, but I really dug her. I think I was the first person who ever did.”

Barbra admits that now. In high school, she’d had a 90-plus average, no dates, no friends. At home, she used to lock herself in the bathroom, smoke, glue on false eyelashes, throatily emote TV commercials in the mirror, and dream of becoming a Great, Great Star.

“I hadda be great. I couldn’t be medium. My mouth was too big.”

One night Elliott took Barbra to a horror movie about giant caterpillars that ate cars, and then they went to a Chinese restaurant. About 2 am it began to snow.

“We were walking around the skating rink at Rockefeller Center when Elly chased me and we had a snow fight. He never held me around or anything, but he put snow on my face and kissed me, very lightly. It sounds so ookhy, but it was great. Like out of a movie!”

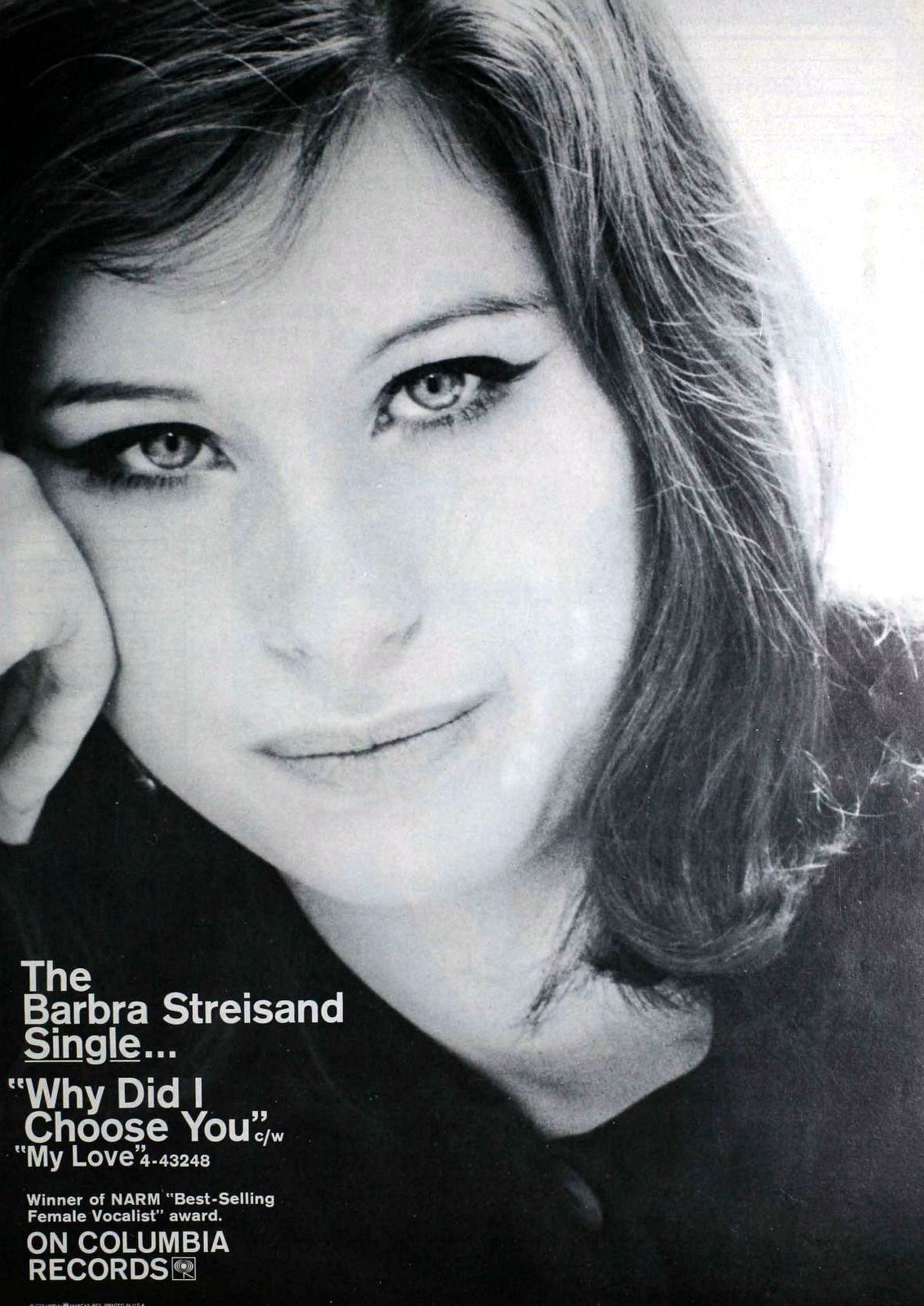

Success is, isn’t to ‘funny’ Barbra (1965)

by Barbra Streisand — The Austin American Sun (Austin, Texas) June 6, 1965

Lately I’m often asked, “what does it feel like now that you’re a big star?”

That question always stops me dead. My first impulse is to say, “why don’t you ask a big star?” Then I realize they really mean me. Well, I don’t know how it feels to be a big star. Just how it feels to be happy, to be hungry, to be cold… to be sleepy.

What seems to have changed primarily is the way people treat me now. One day I was hailing a cab on a street that was filled with puddles from a recent rain. As the taxi stopped for me, a teenage boy ran over and threw his jacket over a puddle. I was completely stunned and then embarrassed, for both of us.

I stammered, “Please, please, pick up your coat. You shouldn’t do that for me. Don’t do that for anyone.’’

This kind of ‘‘adulation’’ — or whatever it can be called — is wrong! It’s unhealthy for both the giver and the receiver. How can I repay or even acknowledge that kind of attention?

What I want is to be respected for my talent, to be appreciated for whatever enjoyment people experience listening to a record or watching “Funny Girl’ or a TV show.

After all, why else should a performer be revered? Am I a doctor who went to school for eight years? Am I a scientist who has discovered some important principle in nature? These are people I admire because of the training and discipline involved in their accomplishments. Since years of struggling were relatively short, success happened so quickly that I didn’t have time to change as a person does who goes through many disappointments.

I’m neither blase nor jaded. Essentially, I’m the same girl who was never in a night club until I was booked as a singer.

On the other hand, success brings responsibility and responsibility brings maturity. I was late 36 times for my first show, “I Can Get It For You Wholesale,” during its nine- month run. I’m hardly ever late for ‘‘Funny Girl”? because being the star of a Broadway show is an enormous responsibility and I feel it.

Success has another effect I’ve noticed. Not so long ago, I remember when I wasn’t treated with normal respect. When casting agents shut the door on me. When, if I wasn’t wearing a $200 suit, I couldn’t get the attention of a salesgirl in an exclusive department store. This side of the spectrum was not so pretty.

Fame is also having almost no time to read a book or go window shopping; being asked for an autograph in a restaurant when your fingers and face are greasy from spareribs; getting threatened with a lawsuit at the slightest problem — all the pockets of reality that I couldn’t know about when as a child I dreamed of stardom.

Without sounding contradictory, I do enjoy my success and I’m immensely pleased and flattered. I love the fan letters that begin, “I’ve never written*a fan letter before…” or, when someone comes back- stage after a performance unable to speak because he was moved… that’s great! Then I feel I’ve really gotten through. That something special happened to this person in the theater.

Quite honestly, a “warm” response is rather a letdown. But when they applaud loudly and shout, I work all the harder because I know what’s true and untrue in the theater,

Matinee audiences are my favorites. Especially Saturday. I think because they pay half the price, they’re twice as willing tc laugh with half as much to lose. They’re already pleased because they’ve saved some money, so they’re in great spirits the minute they hear the overture,

It amazes me that people wait at the stagedoor, but I love it that they do. My fans, as a matter of fact, are an active crowd. They actually participate in my career. For example, I mentioned in my program biography that I collected antique fans — not people. I’ve received dozens of fans in the past year. All kinds: Japanese, ostrich feather; hand-painted, lace, Spanish. I use them to decorate my dressing room. I also receive poems and beautiful paintings.

It’s also very thrilling to receive mail from overseas — from an Army station in Antarctica, a boy in Japan, a Peace Corps worker in Sierra Leone, a government official in Thailand — who also sent a lovely piece of handwoven silk. I’ve even gotten mail from a convict in a Michigan prison.

But, fame is funny, It’s more fun trying to get it than it is to have it.

Recently I watched a rehearsal of the Royal Ballet. Sitting in the audience, I envied — not the exquisite grace of Dame Margot Fonteyn — but any one of the girls in the corps de ballet who dream at night of someday becoming the prima ballerina.

- Audio CD – Audiobook

- English (Publication Language)

- 06/27/2025 (Publication Date) - Columbia Records Group (Publisher)

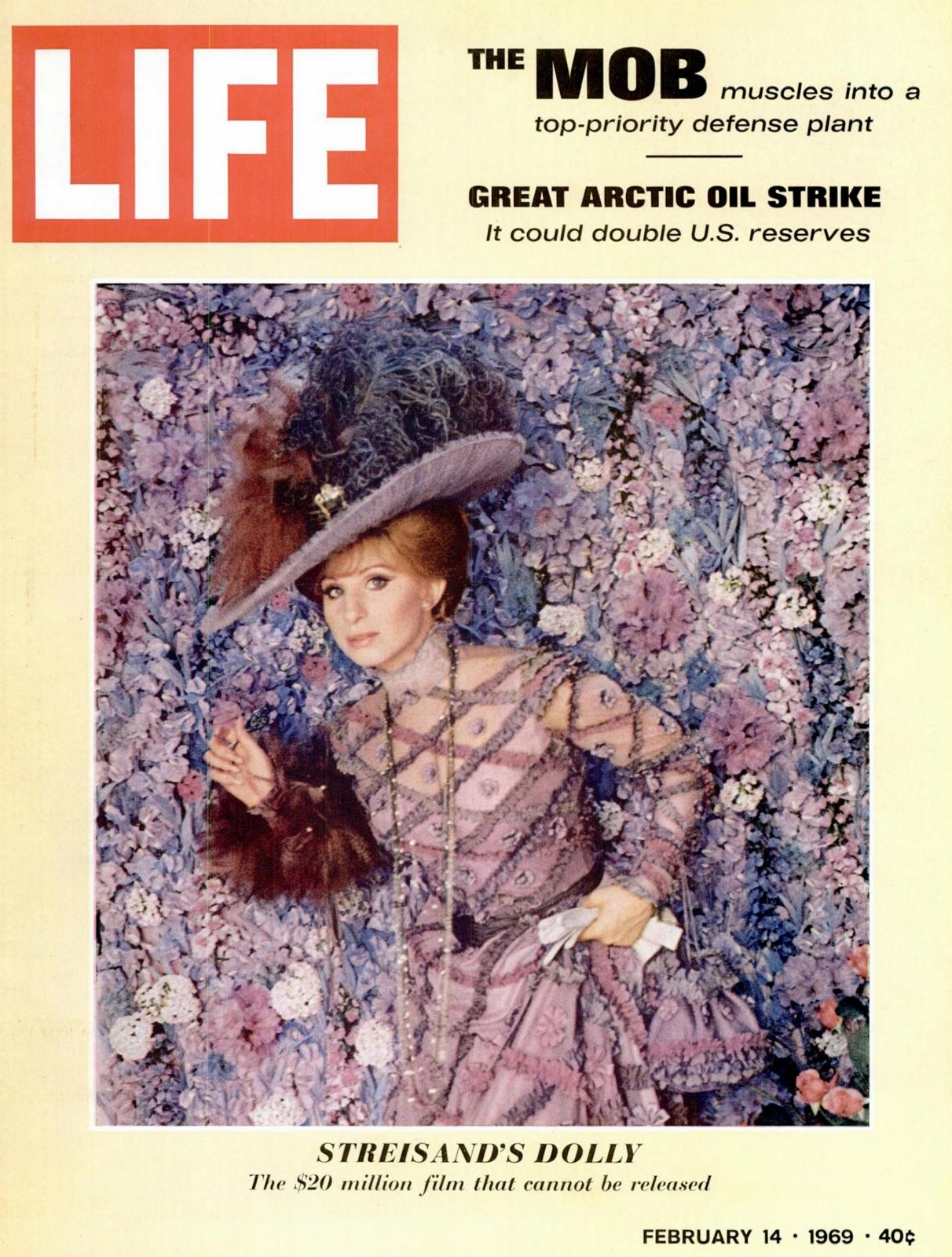

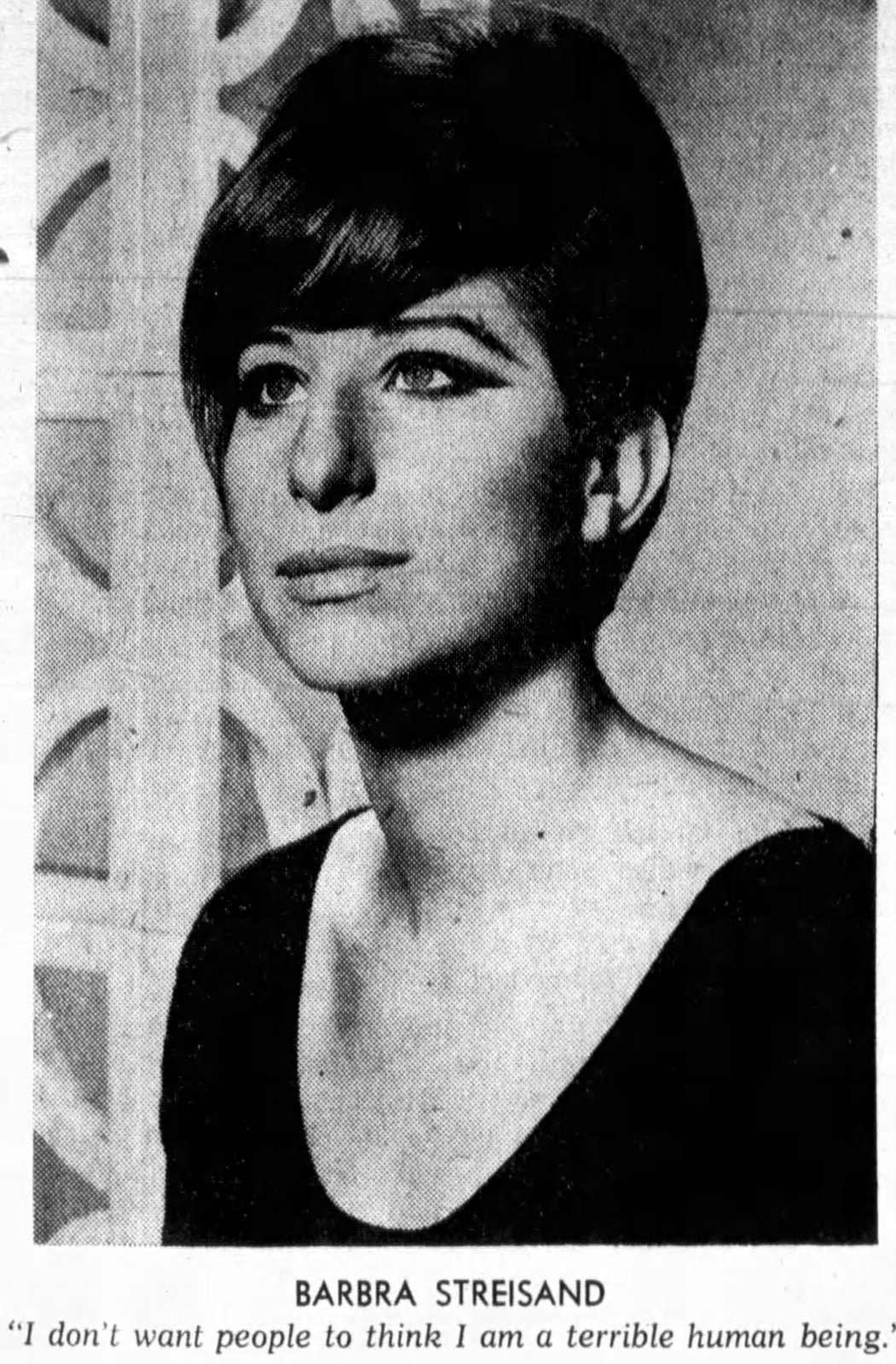

The real Barbra Streisand (1968)

from The Courier News (New Jersey) July 12, 1968

Success is a bittersweet lollipop. It has brought fame, fortune and acclaim to Barbra Streisand in every major branch of show business. But Brooklyn’s onetime homely duckling is annoyed by reports that she is imperious, temperamental and sometime difficult to work with.

“It annoys me to be judged by people who don’t even know me,” she remarked during a midday break in location shooting here of scenes from her forthcoming $20-million dollar costume film, ‘‘Hello, Dolly!”’

“They go by hearsay. It confuses me.”

But she is disturbed at the thought the public may get a distorted idea of the kind of person she is.

“I’m afraid they may think I’m some kind of monster,’’ she said, cutting off a small piece of steak to feed her 18-month-old son, Jason Emanuel.

“I don’t want people to think I am a terrible human being. I’m not. If I were, it would show through on the screen. You can’t really fool anybody on the screen.

“But when you are a star, you are an open target — and the bigger the star the bigger the target.

“You can’t win. If you’re bitchy and pompous, they don’t like you. If you’re normal and unassuming, they say you’re uninteresting.

“If you ride in a chauffeur-driven limousine, they think you’re acting hotsy-totsy — showing off. But if you drive the limousine yourself, they don’t like that either, so” — she laughed and made a grimace — “maybe you’d better just walk to work.”

Analyzing her own personality, Barbra said: “You have to be yourself, no matter what. I have always wanted to excel in anything I tried — to be the very best.

“I feel that self-doubt is both my biggest virtue and my worst fault. Self-doubt is a virtue because it never lets me assume anything. I feel it’s better to be open and vulnerable to hurt in doing one’s work. But self-doubt can be a fault also. In everyday life people can take advantage of it — and wound you.’’

People at the top of the success ladder sometimes have inner torments unknown to those at the bottom. What is Barbra afraid of:

“I’m afraid of myself on a personal basis,’’ she replied, “but not about my career or work. That’s where I have courage.”

A person’s likes and dislikes are usually keys to their character. Here are some of the things Barbra likes:

“Gardenias, Victorian furniture, small, fluffy white dogs, sea smells and country sounds, Oriental philosophy and Chinese food, being in the middle of reading 10 books at a time, soft drinks, all kinds of hats, art nouveau, antiques….

“Indian music, because it has the sound of the soul, early morning, big, soft, floppy beds, working hard and being sometimes lazy, too, muted subtle colors, people who really care about what they do, and tall, dark, handsome men who have a sense of themselves and feel their own worth.”

Barbra a shorter list of dislikes:

“Eggs, hospitals, bright red colors, liquor, the smell of ammonia, vulgarity, flat notes, and people who assume too much familiarity too quickly.’’

Summing herself up, Barbra smiled and said: “I’m really a conglomerate of contradictions. But how can you appreciate the summer if you never have the winter?”