Walt Disney opens new road to screenland: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938)

By Cyrus Le Roy Baldridge – Sandusky Register (Ohio) February 13, 1938

Four weeks ago, Manhattan’s adult population — including its sophisticates — went starry-eyed. Revealing a touchingly childlike — and unsettled — capacity for enchantment, it succumbed to a Princess in a land that never was.

Broadway has, this season, more than its usual quota of successful plays, dealing with a wide range of subjects and including such novelties as a “Julius Caesar” without scenery, soon to be exported to London, as well as a class-conscious musical satire enacted by union workers from the needle trades.

But the dramatic entertainment most widely discussed for the past four weeks has been Walt Disney’s first full-length film, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Its opening was marked by a thunder of ecstasy from the motion picture critics, those tired-eyed indefatigables whose columns were filled, next day, with glittering adjectives.

The Disney movie’s success in New York City

The giant theater, The Music Hall of Radio City, seats 6,720 people. Five times a day a film is shown. (You can do the arithmetic for yourself.)

Meanwhile, the thunder of ecstasy has not abated. It has been increased to deafening proportions by the thousands of adults who have elbowed their way into the theater, standing rain or shine, during the first 10 days in box office queues whose length created a traffic problem for Manhattan’s police.

But now, high above the thunder, shrill noises are audible. They are being emitted by members of Walt Disney’s own profession, by artists whose opinions it is gleaned that the motion picture critics and the thousands of enchanted moviegoers have been strangely misled.

For it has been discovered by artists, who have begun writing to the press, that the neck of Snow White is “uninventive!”

So great is the achievement of Walt Disney and his staff that they obviously require no champion.

However, by weighing the protests against “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” it is possible to appreciate more fully the significance of that achievement not only in the entertainment field but in a field where the motion picture industry’s repeated failures have evoked no comment, the field of art.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

It has been charged that Snow White, her lover and his white charger are “badly drawn attempts at realism,” at factual representation, and that their attempted realism besmirches the whole picture’s fantasy.

I have never met a dwarf, hence I am unable to say whether the seven dwarfs are ill or well-drawn. I can only say that, to Disney’s everlasting credit, they are consistently lovable and never monstrous.

I propose, however, to champion Snow White.

The Princess — a lineal descendant of Disney’s Spring — is represented as possessing a full complement of human physical attributes, although her eyes are too large, too round, and too far apart, while her neck is “uninventive” (it does not articulate in a precisely normal fashion) and her body lacks substance, as a consequence of which she moves with a liquid grace to which well-muscled and well-articulated contortionists sometimes achieve.

But this does not constitute an unsuccessful attempt at realism, at naturalism. For how else could Snow White be portrayed?

Were she either more or less naturalistically conceived, she would fall to be what I assume her to be, neither realistically human nor yet an unrealistic elf, but a fairytale Princess who, having nothing to recommend her but an innocuous prettiness and a sweet perfection of conduct — which would incite any but a fairy tale prince to murder — is a symbol.

Chaste and harmless as a snowflake, she is a symbol of all the good and pretty fairytale Princess who live happily ever after.

Her Prince condemned as a “cardboard lover,” a symbol of all the fairy tale Princes who had fairy tale Princesses; while his white charger, cited as an example of bad realism and, therefore, a “carousel horse,” is a symbol of all the fairy tale horses upon which Princesses ride off; and the Queen is a symbol of all the Wicked Stepmothers by whom the Princesses are traditionally ill-treated.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs movie trailer (video)

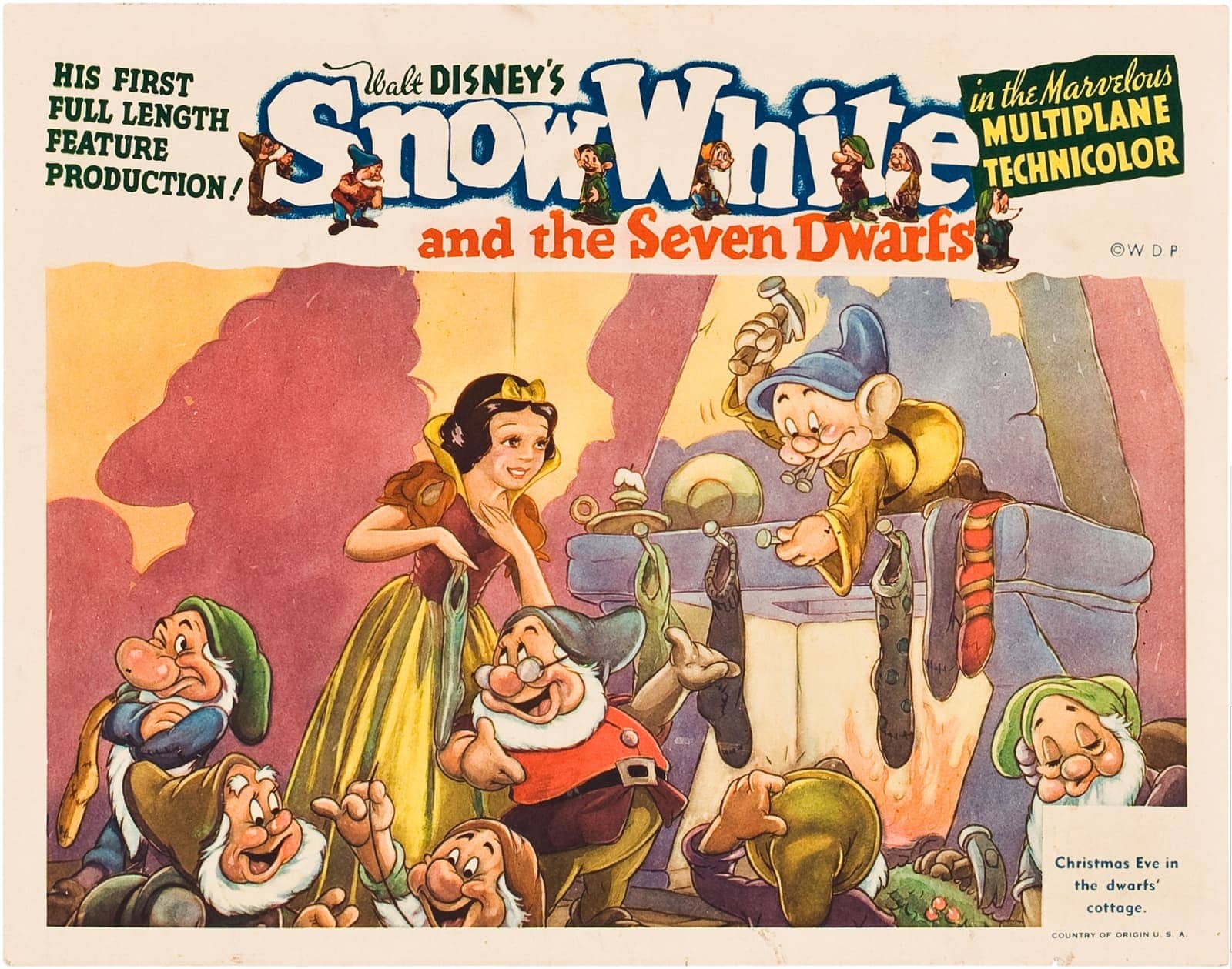

Vintage Disney movie poster for Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

His first full-length feature production

The Seven Dwarfs sing “Heigh-Ho”

Looking back from 1976: What time wrought on Disney lot 39 years after the birth of ‘Snow White’

Sunday News (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) January 11, 1976

The building where “Snow White” was born 39 years ago serves little purpose now except as a testament to change — and a place to store studio props.

Frank Thomas remembers the way it used to be. . . before animators moved to more modern quarters. . . and while Walt Disney was there to father the incomparable cartoon characters the world would adopt as its own.

Thomas, one of five “old-time” artists still employed by the firm, is a vital gentleman in his 60s whose appearance belies his age. . . who speaks with gusto about current cartooning trends. . . but who recalls the old days with a sense of wistful longing.

WALT’S TOUCH MISSED

“Today we have a pretty free hand, because nobody around here really understands what we’re doing,” he smiles.

“When Walt was alive it was different. He was always pushing us beyond our capabilities, asking us to do things one had never done before. And somehow we always managed to deliver.”

The industry predicted Disney was pushing his workers into a disaster when he dreamed up “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.”

Instead, the first seven-reel, feature-length cartoon that was three years in the making turned out to be a true milestone in Hollywood history — drawing an audience of over 20 million people in its first three months of release.

And — currently in its fifth theatrical reissuance since its 1938 premiere — it has racked up international rentals far in excess of $40 million.

“We started out with a budget of $150,000,” recalls Thomas. “And before we were done had spent $1,500,000 — and had run out of money.

“Toward the end, we weren’t drawing paychecks, but we didn’t mind. Walt had everyone so fired up, so involved and caring about ‘Snow White’ — we all stayed with it until the end.”

He grows silent for a moment, staring out a commissary win-dow to the tree-lined walkways and rows of beige stucco cottages that make the Disney studio appear more like a small-town college campus than a big-time Hollywood film factory.

MICKEY’S HOUSE

It’s the “house” that Mickey Mouse built — long before Snow White was even a gleam in Walt Disney’s eye — its foundation built during the period of 1923 to 1937, when he created 168 short cartoons.

Thomas recalls that by the 30s, Disney could see the double-feature movies squeezing his “extra added attraction fillers” off the screen. He could also see that for feature-length animation, detailed development of character would have to be planned.

“He made us realize we would have to come up with different personalities for each dwarf in the ‘Snow White’ story. Once that sunk in, we were going around the halls shaking our heads and muttering, ‘Seven of ’em. . . seven!’ ”

Seven plus those who never made it to the finals, “Like one little fellow we dreamed up named ‘Deafy’ — who went around saying ‘Eh?’ and ‘What?'”

ALSO SEE: Classic Walt Disney Home Video VHS movies & short collections from the ’80s & ’90s

Thomas learned from the cartoon master that, “An animator must really know and like his characters if they’re to come effectively to life on screen.”

Development of the personality is of prime importance. And when the character seems unreal, without dimension, it’s because the artist didn’t take the time — or didn’t have the time — to get to know his “child.”

Disney, he recalls, cared so much about the conception of his “children” that, “When one of us figured out a fresh aspect to a character, or solved a ‘personality problem,’ he’d react with tears of emotion. Do you realize what that means to an artist?”

It also meant a lot when Disney threw himself into development of scenes, “Like he did the time he came back from a camping trip with imitations of how his companions looked and sounded when they were asleep. He was sure we could use the information for a ‘Snow White’ scene.

“We did, even though his imitations were pretty poor as he showed us the open-mouth-to-the-side snorer who went ‘HNAUGHH’ and the pushed-out-lip snorer who made a ‘PHUMP’ noise.”

Such business kept the “Snow White” army of artisans whistling as they worked, Thomas would tell you. But he’d also tell you he resents people who give the impression that landmark production was the only classic production his firm ever turned out.

“When someone asks why another ‘classic’ like ‘Snow White’ wasn’t made, I respond, ‘What about ‘Cinderella‘ or ‘Bambi‘ or ‘Pinocchio’ or ‘101 Dalmations’ or ‘Fantasia.’ Weren’t they also classics?’

“And what about ‘Sword in the Stone?’ Some of the best animation that’s ever been done was in that 1963 cartoon feature.”

But what about the more current Disney cartoons — and the animated productions being made by other firms today?

Thomas concedes that “Robin Hood,” the last full-animated production of the Disney stable, was not in the same league as some of the vintage classics. And from the way he talks, one gets the impression it might be hard for “The Rescuers” — the cartoon story of two brave mice which is currently in preparation — to match old-time standards.

Though a budget of $6 million is being allocated for “The Rescuers,” only 135 animators are employed on the project — as opposed to a team of 750 artists who lent their talents to “Snow White.”

“When Walt was with us,” says his long-time employee, “he was always telling us not to cut corners.” Sometimes, it would appear, the firm would have been better off if corners had been trimmed.

“There was a time,” recalls Thomas, “When Walt was hiring so many extra people we spent more time supervising their work than doing our own. When he finally discharged 500 employees — production went up 25 percent.”

Today, he relates, conserving costs is the name of the animation game, and he predicts, “With the way prices are spiraling, some drastic changes will have to be made, new techniques will have to be developed.”

Already in use as a substitute for hand-etched artisan creativity is the process called “Xerography” in which individual backgrounds need not be drawn for each frame, and character sketches can be overlaid over the Xerography background.