The history of antique & early American weathervanes (1939)

Article by Rita Wellman – House Beautiful magazine (February 1939)

HANDICRAFTSMEN are the only group in civilization who are really happy, William Morris once said, because in their daily work they experience their greatest pleasure.

The men who in the earlier days of this country carved figureheads and other ornaments for ships, shop signs and figures, and the models from which weathervanes were hammered up or cast in metal, were the type of craftsmen admired by Morris — men who worked well at what they liked to do.

Although they were the inheritors of an age-old tradition, they designed almost as innocently as the aborigine, and yet they had the stimulus of having to meet certain practical requirements which called upon them for precision and technical skill.

They learned from one another and were thoroughly trained in the shop practice of their craft. The conflicting theories of formal art bothered them very little.

They considered themselves artisans and craftsmen, and didn’t dream of calling themselves sculptors. Few of them thought it of enough importance to sign their names to their work, and what local fame any of them may have had in their time has not, except in a few instances, survived them.

The names of William Rush, of Philadelphia, and Samuel McIntire, the architect of many Salem houses, are identified with fine carvings, though neither is known to have designed weathervanes.

The coppersmith Deacon Shem Drowne, a typical Yankee craftsman who made a number of weathervanes in the mid-1700s, was famous in his day as the carver of the glass-eyed grasshopper vane on the cupola of Faneuil Hall in Boston.

In the making of weathervanes for church steeple tops, county courthouse cupolas, barn gables and the roofs of private houses, American craftsmen from the seventeenth century to the latter part of the nineteenth had a particularly happy task which they carried out in high spirit.

They worked in the satisfying materials of wood and metal, and they were conscious of the fact an element in their design, and an important one, was the sky itself.

Among pre-Revolutionary vanes of iron, wrought at white heat over charcoal fires in village smithies, are examples which show the strong traditional feeling of men who were not yet detached in spirit from the Old World.

ALSO SEE: Early American portrait miniatures: See 38 tiny pieces of antique art history

(Yet the American desire independence must have been born in the smithies, for of all the early Colonial industries, the iron industry had the most difficult times, and its struggle to get established was “a task fitting for heroes.”)

It is in the latter part of the eighteenth century at up to the last quarter of the nineteenth that the originality, vitality and humor of the American vane makers is asserted —

the numbers of animals that form a new and ingratiating heraldry, a heraldry of democracy.

Associated with medieval heraldry is one of the earlies weathervane forms, the banneret, derived from the knight’s pennant with his bearings or crest.

From the knight’s privilege hoisting his banner to his turret top after he had won a victory, the idea of the weathervane, as a gallant decoration for a building — apart from its utilitarian purpose — originated.

The are many well-known banneret forms among seventeenth- and eighteenth-century weathervanes made in the United States.

The bodies of these vanes are often quite simple, mere hinged metal, often with pierced monograms, sometimes with more than one on a single piece, and nearly always with the date.

But their standards were usually elaborate, with fine scrollwork or signs and with a cross-piece, also decorated, bearing comp pointers.

A stylized form grew out of the solid pennant design; this had openwork patterns which, combined with a support of scrollwork and spirals, made the vane a fine architectural accessory.

The stylized form appears often in vanes made by Pennsylvania German craftsmen, skillfully designed and wrought pieces decorated with conventionalized variations of the Palatinate tulip and with star finials.

Many of these vanes are wrought in such elaborate designs, spread in branching and lacy silhouette against the sky, that only the most expert balancing and skillful use of bracing units has enabled them to stand up for centuries.

All over Pennsylvania, important buildings, homesteads and the big red Pennsylvania barns were graced by these handsome Revolutionary vanes.

ALSO SEE: The beauty of antique kerosene lamps – and how one invention changed the way people lived

Antique American weathervanes

1. A weathervane inspired by a Currier & Ives print of Ethan Allen and Sulky, is late nineteenth century. Of sheet copper in the round.

2. From Bortholdi’s Statue of Liberty comes this of the same period.

3. Indian with bow is early nineteenth century, pointed sheet iron, Nadelman Collection, New York Historical Society.

4. Mid-nineteenth century pig of sheet copper, painted buff.

5. The eagle weathervane was found on Long Island, is late nineteenth century. It is made of sheet copper stamped in the round.

6. A racing, Kentucky type of horse from 1880, in gilded zinc. At the Edison Institute.

7. The Angel Gabriel from the nineteenth century.

8. An iron and sheet metal rooster, late 1800s, atop a Providence fire station.

9. An American bowling idyll weathervane.

10. An Indian chief, circa 1860, stands on the an art studio.

11. The fish form comes from Europe, where it was a protest against the papal decree for cocks on church steeples.

12. Late eighteenth or early nineteenth-century cock weathervane, from Helena Penrose.

13. An early nineteenth-century deer, courtesy the American Folk Art Gallery.

14. A Joseph Rothenberg sketch of a horse belonging to Carolyn Scoon. The drawings are courtesy of the Index of American Design, WPA Federal Project.

MORE: Two dozen fashionable Victorian fireplaces from the 1880s

Antique weathervanes, and their windy place in history

Carved wooden vanes went out with the figureheads in ships

When a Phoenician sailor stuck a needle through the stem of a feather and held it out in the wind, he invented the first weathervane, or feather vane.

He was nearly equaled by the Indian boy who was taught to moisten his finger in his mouth, and to hold that finger aloft in the air. When that finger grew cold on a certain side, the Indian child knew that the wind came from that particular direction.

The Phoenicians, however, were probably the first of all civilized peoples to put the vane of feather into practical use.

Since those early days, weathervanes have been used in every form and by all races, says the N.Y. Recorder. Modern vanes in their resent shapes were first made in wood, by traveling carvers and later in copper by tinkers and smiths.

They were used on poles, churches, public buildings, ships and were placed on rocky points of land along the seashore.

They are now made in every conceivable design and pattern. Horses, cows, deer, eagles, ships, roosters and even pigs are hammered out in copper and used to register the direction of the wind.

The newer vanes have rain-cups, attached for catching water during a storm. The amount of water that falls is measured by the square inch in a tube under the vane.

Wind gauges also are attached. These indicate the speed of the wind. The gauges are small cups hung sideways to the vane.

The wind blows them around in a circle and the revolutions are registered by electricity. Nearly all the large weathervanes in town are connected with dials in the buildings below.

The dial is round like the face of a clock, lettered like a compass, and a revolving hand shows the action of the wind on the vane overhead.

ALSO SEE: 9 ornate Southern-style wrought-iron balconies

Vanes are no longer set in sockets, as it is nearly impossible to keep them properly oiled. They are hung loosely, like a cap on a pivot, and the hollow stem of the vane hangs over the head of the pivot, covering it from rain and rust.

One of the largest vanes ever seen in New York was placed on the post office about fifteen years ago. It was so large that it was considered unsafe and was taken down. A good drawing of it is still in existence.

The arrow, scroll and banneret seem to be favorite shapes in vanes at present. The fence-jumping horse and the plow are yet found on the grounds where country fairs are held. but they are not in great demand.

The tobacco leaf vane is found largely in the South and in Connecticut. The spread eagle and running deer are wind signs in the western states, the deer more particularly in Canada. Malt barrels in copper are placed on breweries throughout the country. – From the Arkansas City Daily Traveler (Arkansas City, Kansas) – January 30, 1892

On one farm in Kansas: “The weathervanes on the roof indicate the particular breed of stock; thus, one vane is a rooster, another is a horse, while a third represents a cow.” – Nemaha County Republican (Sabetha, Kansas) from December 24, 1887

MORE TO SEE: Vintage Pennsylvania Dutch and other Colonial-style barn signs for good luck (1959)

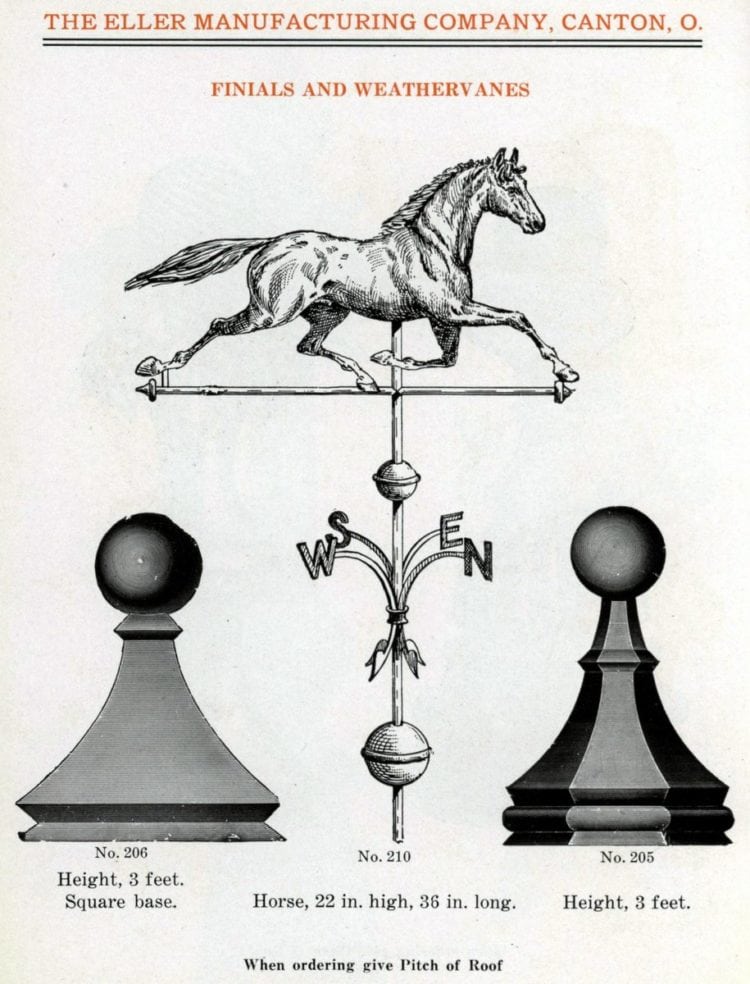

Antique weathervanes and finials from the 1910s & 1920s

ALSO SEE: Americana quilts you can make of pieced patchwork

ALSO SEE: How people used vintage washboards, wringers & other old-fashioned laundry equipment years ago

Antique 1920s weather vanes from J.W. Fiske Iron Works, New York (1921)

We are generally recognized as the oldest and most extensive manufacturers of weather vanes in the United States.

In our business career of sixty-three years, we have accumulated not only a great variety of stock designs, some of which are illustrated in the following pages, but also experience that enables us to prescribe the Fiske standards as those that should be demanded by all purchasers of weather vanes:

1. The basic metal should be sheet copper or brass (not a combination of zinc and copper) and mounted on brass tubing.

2. Vanes should be gilded with the finest gold leaf so that they will remain bright and not corrode.

3. The letters and balls should be well gilded.

4. The spire (which is included in the price of each Fiske vane) should be of wrought iron with a hardened steel spindle for the vane to turn upon.

5. Eagles should be full-bodied with double-thick wings.

6. Each vane should be a perfect indicator of the wind.

The Fiske line of weather vanes has been unparalleled for a long time and yet new and original designs are being added constantly.

ALSO SEE: Need vintage home restoration inspiration? See 60 authentic tile patterns from the ’20s

MORE: Old Edwardian wallpaper styles & home decor, plus 40 real paper samples from the early 1900s

ALSO SEE: 62 beautiful vintage home designs & floor plans from the 1920s