The world wondered what the astronauts would say when they landed on the moon (1969)

First up here is a little pre-landing speculation from a reporter at a Florida newspaper, near the Kennedy Space Center launch site.

The Orlando Sentinel (Florida) July 18, 1969

SPACE CENTER, Houston — The first words Neil Armstrong utters from the moon’s surface this weekend will go down in history one way or another.

It’s the “another” that has phrase-conscious historians worried.

The problem is Armstrong himself. His tremendous scientific abilities don’t extend to turning colorful phrases, and he is not likely to bring tears to earthlings’ eyes with anything that would threaten the Gettysburg Address.

Armstrong not told what to say

The astronaut has said repeatedly no one has told him what to say on the moon. And although there have been thousands of suggestions from the general public he says NASA’s flock of flacks haven’t prepared a speech for him.

“It will all depend on my emotions once I get there,” he told a recent press conference. “I don’t know what my emotions will be.” (Incidentally, that was his most memorable quote of the conference.)

MORE: Apollo 11: The speech Nixon would have given ‘in event of moon disaster’ (1969)

Some wags put tongue in cheek and say he has no emotions. They recall the Gemini 8 flight when an electrical short circuit in a thruster forced him to manually bring the craft to a safe emergency splashdown.

The world was on edge there for awhile, but Armstrong didn’t seem to have any emotions.

Words from the man on the moon

So, when Neil Armstrong slips down from the lunar module, countless millions of people around the world will be watching and listening.

And the first words they hear might be something like:

“Well, here I am on the moon . . .”

BEFORE: Today, July 20, 1969: A date with history – Man will try moon landing

By Gary Blonston

HOUSTON — This is the day men land on the moon.

If all goes well — and everything has so far — the gentle landing in the Sea of Tranquility will occur at 3:15 p.m. Detroit time — four days, six hours, 42 minutes and 32 seconds after Apollo 11 blasted from the pad at Cape Kennedy.

Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin and Michael Collins, have spent most of that time in a competent, almost leisurely calm, but they knew as they went to bed Saturday night that the easy part is over.

Riding a lunar orbit that swells from 62 miles to 75 miles above the moon, the Apol!o crew will get up Sunday morning to the most demanding list of duties they have ever faced. Their lives and a dream as old as man depend on their doing all those things right.

But the burden for preserving those lives and that hope rests just as much with machinery — rocket engines, radar, computers — the accouterments of ultra-technology in pursuit of a primeval goal.

They all must work, and most of all a grotesque bug-legged silver craft named Eagle must work — down and back.

The lunar module has hitchhiked all the way from earth, visited only twice by the crew for general inspection, preflight preparation and communications testing.

ONE OF THOSE visits came Saturday night, as LM pilot Buzz Aldrin entered the LM for radio tests. It was the first time Mission Control was receiving voice and telemetry signals from both lunar and command modules and the first time the identification code names Eagle and Columbia have been used between earth and moonships since Apollo 11 left.

The tests went very well,

“You’re beautiful, Eagle,” Houston communicator Charley Duke said in response to a crystal-clear voice from the LM 8-band radio.

“(This is) Eagle, Houston, you’re gorgeous also,” Aldrin answered.

It was the LM’s first active involvement in Apollo activities since the flight began.

Sunday it will become totally involved.

THE ASTRONAUTS have been in circular mode orbit ranging from 61.8 to 75.4 miles above the moon ever since a pair of rocket firings Saturday afternoon that slowed their speed.

Without the braking blasts, they would have come speeding back to earth in a free-flying return.

The two engine burns, one 21 minutes long, the other a more precise adjustment 16.4 seconds long, occurred four hours apart, interrupted by the astronauts’ first color television broadcast of the lunar surface.

Both firings of the big service module engine were made on the radio-dead back side of the moon, and Mission Control twice waited in suspense through 25-minute silences before they learned the orbital-insertion burns were successful.

THE FIRST, longer firing was most critical, slowing the Apollo craft from 5,500 miles an hour to 3,500 miles an hour and dropping it toward the moon.

Mission Control was hushed as the time approached for Apollo to emerge from the back of the moon.

Finally, at almost the predicted second, the radio crackled: “Madrid AOS” — the Madrid receiving station had ‘acquisition of a signal from the moonship as it turned the big corner from moon back to moon face on the way through its first lunar orbit.

Both burns were almost precisely what the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had in mind when it drew up plans months ago.

Asked by Houston after the first burn for data on various technical elements of the critical firing. Armstrong radioed back: “They were like perfect.”

The dimensions of the second orbit, from which Armstrong and Aldrin will depart for their fall to the lunar surface, were only one-tenth of a mile off what NASA had anticipated.

After that second firing, the Apollo crew had 10 lunar orbits ahead of them before Armstrong and Aldrin would leave the command module for their trip down.

They visited the lunar module tor the second time Saturday night, continuing pre-flight preparations in the little craft.

Aldrin will enter the LM Sunday morning at about 8:30, followed about an hour later by Armstrong but they will have almost 3-1/2 hours of work to do inside the lunar lander — activating and checking the systems that will keep them alive and on course before they undock from Mike Collins’ command ship.

THEY WILL break free at about 12:43 p.m.

They will drop almost 60 miles in the next hour, down to the 50,000-foot altitude that was the end of the line for the Apollo 10 moon approach rehearsal in May.

From that point on, Arm- strong and Aldrin will be pioneering space techniques and experiences no men have ever been through before.

At 3:03 p.m. they will fire Eagle’s single descent engine, capable of 9,870 pounds of thrust on an exotic fuel mixture of helium-pressurized aerozine 50 and nitrogen tetroxide.

There is no spark plug in the engine, merely two spigots. The two fuels ignite on contact with each other, making the descent engine as simple and foolproof a machine as it can be.

It will burn constantly for 12 minutes — the longest engine firing in space history.

FLYING ENGINE-first, Armstrong and Aldrin will be essentially lying on their backs until they are within seven miles of the landing site on the western edge of the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

They will not see their target until less than four minutes before they hit it.

It will be an automatic approach until the LM is about 500 feet above the moon, Then Armstrong and Aldrin will take over the steering.

Then, about 3:15 p.m., slowed from thousands of miles an hour to three feet a second, a manned spacecraft will settle onto the moon.

The two moon men are scheduled to spend almost 10 hours in the LM before emerging, but they are an independent pair, and they conceivably could leave early. It is entirely up to Armstrong.

If they stick to their timetable, they will check out the LM to see that the landing has created no mechanical problems, eat and rest for four hours.

WHILE ARMSTRONG and Aldrin are preparing for their exit, Collins will aim his color TV camera down toward the landing site of his comrades and send pictures to earth from 69 miles above the moon.

Armstrong will be first out of the LM, opening the hatch at 1:08 a.m. Monday.

Almost his first act will be to pull down the black-and-white TV camera that will watch the pair of astronauts for the next two hours and 40 minutes.

Then he will climb down a nine-rung ladder, and at 1:17 a.m. become the first human being to set foot on another world.

Armstrong will be the first to have walked on the moon

He and Aldrin will spend most of their time outside the LM painstakingly setting out three scientific information-gathering devices and collect- ing about 80 to 120 pounds of lunar soil and rock for analysis back on earth, Aldrin will go back into the LM at 3:08 a.m., Armstrong at 3:28. Ten minutes after they step back inside, they will modify their electrical system, knocking out power in the TV camera.

It will not be able to photograph their departure from the moon a little more than nine hours later.

Armstrong and Aldrin will spend 21 hours and 27 minutes on the moon if all goes well, most of their time inside their craft.

But for all the precision of the planning, there is nothing automatic about any of what the astronauts will do. There are a lot of ways the moon mission couldn’t work.

Expressed solely in times and numbers, it seems easy.

But there are mortal men and vulnerable machines up there. The next day of the Apollo 11 mission is a test of NASA’s last eight years, a test of the ingenuity of private and public men in unique cooperation, and a test of those three close-mouthed men up there who have done everything so far so well.

The moon landing transcript from July 20, 1969: One Giant Leap For Mankind

When it comes time to set Eagle down in the [Moon’s] Sea of Tranquility, Neil Armstrong improvises, manually piloting the ship past an area littered with boulders. During the final seconds of descent, Eagle’s computer is sounding alarms.

It turns out to be a simple case of the computer trying to do too many things at once, but as Aldrin will later point out, “unfortunately it came up when we did not want to be trying to solve these particular problems.”

When the lunar module lands at 4:18 p.m EDT, only 30 seconds of fuel remain. Armstrong radios “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” Mission control erupts in celebration as the tension breaks, and a controller tells the crew, “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue, we’re breathing again.”

Armstrong will later confirm that landing was his biggest concern, saying, “the unknowns were rampant,” and “there were just a thousand things to worry about.”

At 10:56pm, EDT Neil Armstrong is ready to plant the first human foot on another world. With more than half a billion people watching on television, he climbs down the ladder and proclaims: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Aldrin joins him shortly, and offers a simple but powerful description of the lunar surface: “magnificent desolation.” They explore the surface for two and a half hours, collecting samples and taking photographs.

They leave behind an American flag, a patch honoring the fallen Apollo 1 crew, and a plaque on one of Eagle’s legs. It reads, “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” – NASA

More of the moon landing transcript from NASA

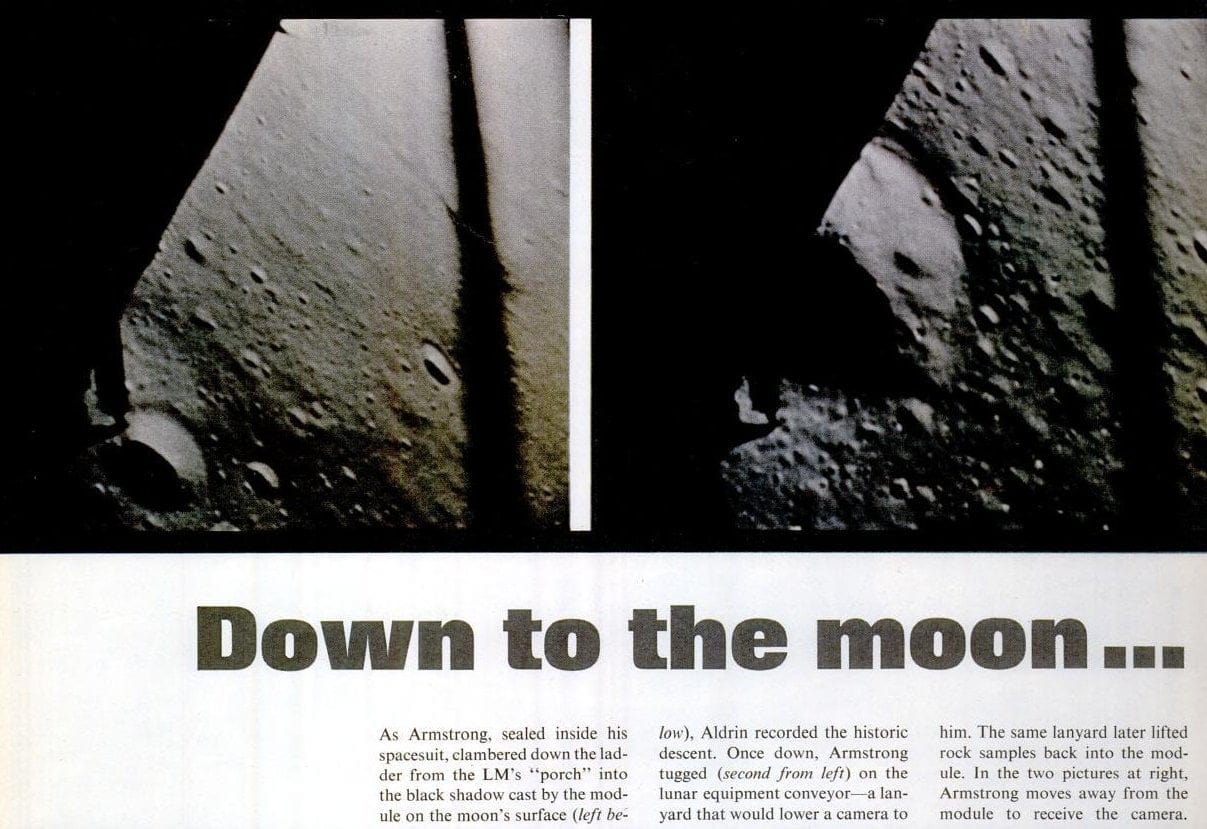

109:22:48 McCandless: Okay. Neil, we can see you (on the TV) coming down the ladder now. (Pause)

109:22:59 Armstrong: Okay. I just checked getting back up to that first step, Buzz. It’s… The strut isn’t collapsed too far, but it’s adequate to get back up.

109:23:10 McCandless: Roger. We copy.

109:23:11 Armstrong: Takes a pretty good little jump (to get back up to the first rung). (Pause)

109:23:25 McCandless: Buzz, this is Houston. F/2 (and)…

109:23:28 Armstrong: Okay, I’m at the…(Listens)

109:23:29 McCandless: …1/160th second for shadow photography on the sequence camera.

109:23:35 Aldrin: Okay.

[The ladder is mounted on the west strut and is, therefore, in the LM’s shadow. The recorded image is fairly dark. Journal Contributor Markus Mehring notes that, as a result of the information from Bruce, Buzz changes settings on the DAC and the recorded scene brightens, “just in time to catch Neil and his historic step off the footpad.”]

109:23:38 Armstrong: I’m at the foot of the ladder. The LM footpads are only depressed in the surface about 1 or 2 inches, although the surface appears to be very, very fine grained, as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder. (The) ground mass is very fine. (Pause)

109:24:12 Armstrong: Okay. I’m going to step off the LM now. (Long Pause)

[Neil has his right hand on the ladder and will step down with his left foot, leaving his right foot on the footpad.]

109:24:23 Armstrong: That’s one small step for (a) man; one giant leap for mankind. (Long Pause)

[After examining the soil disturbance around his left boot, Neil moves his right hand lower on the ladder and steps down with his right foot.]

109:24:48 Armstrong: Yes, the surface is fine and powdery. I can kick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers, like powdered charcoal, to the sole and sides of my boots. I only go in a small fraction of an inch, maybe an eighth of an inch, but I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine, sandy particles.

109:25:30 McCandless: Neil, this is Houston. We’re copying. (Long Pause)

109:26:16 Armstrong: Okay. The descent engine did not leave a crater of any size. It has about 1 foot clearance on the ground. We’re essentially on a very level place here. I can see some evidence of rays emanating from the descent engine, but a very insignificant amount. (Pause)

109:26:54 Armstrong: Okay, Buzz, we ready to bring down the camera?

109:27:03 Armstrong: Okay.

109:27:05 Aldrin: Okay. You’ll have to pay out all the LEC. It looks like it’s coming out nice and evenly.

109:27:13 Armstrong: Okay. It’s quite dark here in the shadow and a little hard for me to see that I have good footing. I’ll work my way over into the sunlight here without looking directly into the Sun.

109:27:28 Aldrin: Okay. It’s taut now. (Long Pause)

109:27:51 Aldrin: Okay. I think you’re pulling the wrong one.

109:27:55 Armstrong: I’m just…Okay. I’m ready to pull it down now. There was still a little bit left in the (LEC bag)…

109:28:01 Aldrin: Okay. Don’t hold it quite so tight. Okay? (Garbled) (Pause)

109:28:17 Armstrong: Looking up at the LM…I’m standing directly in the shadow now, looking up at Buzz in the window. And I can see everything quite clearly. The light is sufficiently bright, backlighted into the front of the LM, that everything is very clearly visible. (Long Pause)

109:28:55 Aldrin: Okay. I’m going to be changing the (garbled, probably the sequence camera film magazine).

109:28:58 Armstrong: Okay.

109:30:23 Armstrong: The (Hasselblad) camera is installed on the RCU bracket. (Pause) And I’m storing the LEC on the secondary strut. (Long Pause)

109:30:53 Armstrong: I’ll step out and take some of my first pictures here.

109:31:05 McCandless: Roger. Neil, we’re reading you loud and clear. We see you getting some pictures and the contingency sample.

109:32:19 McCandless: Neil, this is Houston. Did you copy about the contingency sample? Over.

109:32:26 Armstrong: Roger. I’m going to get to that just as soon as I finish these…(this) picture series. (Long Pause)

109:33:25 Aldrin: (Commenting for Houston’s benefit) Okay. Going to get the contingency sample there, Neil?

109:33:27 Armstrong: Right.

109:33:30 Aldrin: Okay. That’s good. (Long Pause) (Providing some commentary as he watches Neil out the window) Okay. The contingency sample is down (that is, Neil has the sampler assembled) and it’s (garbled).

109:34:09 Aldrin: Looks like it’s a little difficult to dig through the initial crust…

109:34:12 Armstrong: This is very interesting. It’s a very soft surface, but here and there where I plug with the contingency sample collector, I run into a very hard surface. But it appears to be a very cohesive material of the same sort. I’ll try to get a rock in here. Just a couple. (Pause)

[Because the Moon has no atmosphere, the surface is continually bombarded by large and small meteorites – mostly small. Each impact digs a crater and sprays ejecta around the immediate area. The net effect is that the very top layer of the soil is very soft. However, each of the impacts shakes the subsurface layers in the area around the crater, and that shaking tends to settle the subsurface layer and make it denser. Indeed, as Buzz will discover when he tries to drive a couple of core tubes into the surface at the end of the EVA, below about 4 inches, the soil is very densely packed, rather like beach sand becomes after a wave has withdrawn.][Neil collected a total contingency sample of 1015.29 grams, including four rocks, each weighing more than 50 grams (terrestrial).]

109:34:54 Aldrin: That looks beautiful from here, Neil.

109:34:56 Armstrong: It has a stark beauty all its own. It’s like much of the high desert of the United States. It’s different, but it’s very pretty out here.

Moon landing video: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

NASA’s entire annotated transcript can be found here.

AFTER: Space Center, Houston — Man landed and walked on the moon yesterday

More than just the man who made the first “giant leap for mankind,” Armstrong also performed the first manned docking of spacecraft on Gemini 8, and served as a test pilot for planes ranging from the giant KC-135 Stratotanker to the Mach 6+ X-15 spaceplane.

After his history-making flight with fellow moonwalker Buzz Aldrin and command module pilot Michael Collins, the former naval aviator and Purdue University graduate would retire from the astronaut corps and go on to teach aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati.

Though Armstrong had left NASA, in time, he would serve on the panel that investigated the Apollo 13 failure. He was later appointed by President Reagan to the Rogers Commission, which investigated the space shuttle Challenger disaster.

Neil Alden Armstrong was born on August 5, 1930 in Wapakoneta, Ohio, and died in Columbus on August 25, 2012, following complications from heart surgery earlier in the month.

While the man himself is gone, the footprints he left on the moon — and his place in history — will live on forever. – AJW

Nearly seven hours after the lunar module Eagle narrowly escaped disaster in touching down in the boulder-strewn Sea of Tranquillity, 38-year-old Apollo-11 Commander Neil A. Armstrong stepped into history by placing his foot on the moon’s alien soil.

After climbing slowly down the nine rungs of the ladder from the Eagle capsule and stepping out into the bleak lunar dawn, Armstrong radioed his home planet of Earth, nearly 250,000 miles away: “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind!”

It was at 10:56:31 p.m. (EST) when Armstrong first stepped onto the powdery moon soil. Minutes later, at approximately 11:16 p.m., his companion explorer, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., climbed cautiously down the steep ladder to join Armstrong on their moonwalk.

TWO HOURS AND 14 MINUTES after Armstrong first stepped on the moon, the two astronauts returned to their Eagle capsule. At 1:11 a.m. — after unfurling the American Flag on the moon, talking with President Nixon by special radio hookup, collecting lunar soil samples for study back on Earth and installing equipment for scientific research — Arm- Strong and Aldrin reported they were back in their spacecraft.

“The hatch is closed and locked,” Armstrong reported to ground communicator Charles Duke at the Houston Space Center.

The astronauts will remain on the moon, resting and eating in their Eagle capsule, until 1:53 p.m. (EDT) today. At that time they will fire the big ascent engine on the Eagle in a critical burn to blast them off the moon’s surface for rendezvous with the third Apollo-11 astronaut, Michael Collins, in the circling mother- ship Columbia 69 miles above the lunar surface.

The real drama of the historic moonwalk — rescheduled some three hours ahead of time at the astronauts’ request — came when Armstrong emerged from the capsule of the Eagle.

In a bulky space suit that gave him the life-sustaining environment of his own planet, Armstrong climbed laboriously down the ladder to culminate a millennium of human dreams and a $24-billion American space project that opened the doors of the universe to mankind.

When first he emerged from the spacecraft, slowly, cautiously, backing out, the world waited, and waited. He took repeated instructions from Aldrin, “Plenty of room to your left.”

“How am I doing?” he asked. “You’re doing fine,” Aldrin answered. Then he told mission control, “Okay, I’m on the porch.” It was 10:51 p.m.

Armstrong stepped first onto one of the saucerlike foot-pads of his spacecraft, Then the moon. He was in the bitter cold of lunar shadows as the Eagle’s television camera caught the sight of his left foot, Size 9-1/2, pressing into the moon’s crust.

“THE SURFACE is fine and powdered, like powdered charcoal to the soles of my boot — I can see the footprints of my boot in the fine particles,” Armstrong said.

Armstrong said the spacecraft’s four footpads had pressed only an inch or two into the dusty soil. His foot sank only “a small fraction — about an eighth of an inch” — into it, he said.

Armstrong’s first steps were cautious in the one-sixth gravity of the moon. But he quickly reported, “There is no trouble to walk around.”

“It has a stark beauty all its own,” Armstrong said. “It’s different. But it’s very pretty out here.”

THE TELEVISION camera on the side of the Eagle was on him constantly.

A worldwide television audience watched man’s first footfall in a world other than his own.

It was Armstrong’s left foot — shed in a space boot 6 inches wide, 13 inches long, and with a zig-zag sole tread– that impacted first.

That step by Armstrong, an Ohio-born civilian, was a dramatic peak in a day jammed with such moments–the landing itself at 4:18 p.m., and Armstrong’s superb calm when he overrode the automatic pilot of the lunar lander which was taking the spaceship toward a boulder-strewn landing, and manually steered himself and Aldrin, an Air Force colonel, free of almost certain disaster.

Minutes after that historic first step, Armstrong and Aldrin set out on foot to explore the new world of the moon near their spaceship.

After joining Armstrong on the surface, Aldrin said, “Magnificent desolation.”

“Hey, Neil, didn’t I say we would see some purple rocks?” Aldrin shouted a few minutes later.

“Find a purple rock?” Armstrong asked.

“Yep,” Aldrin replied.

He said some rocks were sparkly. Aldrin said he thought one rock was biotite, which is a silicate made of magnesium, iron, aluminum and potassium. It is usually brown on earth.

ALDRIN WALKED ABOUT the surface ape-like, because of the stiffness of his pressurized suit.

“Hey. you’re standing on a big rock now,” Armstrong told Aldrin.

Armstrong removed the television camera from the lunar module storage area and carried it over the surface, clearly showing small craters pitting the surface near Eagle.

Armstrong moved about 40 to 50 feet from Eagle, turned and showed television viewers the ship that carried them to the surface.

The terrain around the spacecraft appeared very flat, littered with what appeared to be small loose rocks and pocked with little craters a foot or two in diameter,

ARMSTRONG SAID the lunar surface was “very, very fine grain.” At another point, he referred to the “sandy surface.”

The astronauts took spectacular television shots of the craggy moonscape, some of them showing the ungainly lunar lander perched on the lunar surface.

The men moved around with a shuffling gait, almost as though they were in a water ballet.

Armstrong placed the American flag on the moon at 11:43 p.m. (EDT), experiencing a little difficulty driving the staff into the lunar soil.

President Nixon phoned the astronauts after their landing from the Oval Room of the White House.

“Because of what you have done the heavens have become part of man’s world,” Mr. Nixon said through 250,000 miles of space. His call lasted about two minutes.

The astronauts saluted twice as Mr. Nixon said his final words.

The first television view millions on earth saw was Armstrong’s foot descending slowly.

Then there was his full figure, shadowy, mostly a silhouette, but it was remarkably clear.

“LOOKING UP at the LEM, I’m standing directly in the shadow now looking up at Buzz in the windows. I can see everything quite clearly,” Armstrong said at 11:01 p.m.

Armstrong picked up a piece of the moon and put it in his pocket.

Armstrong moved slowly in the strange world of gravity only one-sixth as strong as earth’s. But he appeared to have no difficulty.

The dark outline of one of the lander’s four legs was clearly visible on television against the bright background of the sun.

ARMSTRONG appeared as a dark shadow.

At 11:06 p.m. (EDT), he reached down with a sample collector that looked like a butterfly net. He said as he tried to scoop up two pounds of soil, the surface appeared hard and very cohesive.

“It has a stark beauty all of its own. It’s much like the desert of the United States. It’s different but it’s very pretty out here,” Armstrong said.

He said some rocks had vesicles in the surface. That might indicate bubbles from volcanic action.

Television showed Armstrong’s arms working at something on the front of his spacesuit. He evidently was unpacking a camera. He turned, taking pictures.

“Ready for me to come out,” Aldrin asked at 11:10 p.m.

“Stand by just a second,” Armstrong replied.

“OK, you saw what difficulties I was having,” Armstrong told Aldrin as he guided him out of the ship’s hatchway.

Armstrong stood at the foot of the ship’s ladder as Aldrin began his climb down.

“You’re right at the edge of the porch,” Armstrong told Aldrin.

When we first walked on the moon

ALTHOUGH ARMSTRONG’S foot appeared to hit the surface at 10:56:31, the space agency gave 10:56:20 as the unofficial time of his first footstep on the moon.

After he was joined by 39-year-old Aldrin of Montclair, N.J. Armstrong read from the plaque on the side of the Eagle. In a steady voice, he said:

“Here man first set foot on the moon, July, 1969. We came in peace for all mankind.”

During the moments he walked alone, Armstrong’s voice was all that was heard from the lunar surface.

He appeared phosphorescent in the blinding sunlight. He walked carefully at first in the gravity of the moon. Then he tried wide gazelle-like leaps.

Aldrin tried a kind of kangaroo hop, but found it unsatisfactory. ‘The so-called kangaroo hop doesn’t seem to work as well as the more conventional pace,” he said. “It would get rather tiring after several hundred.”

In the lesser gravity of the moon, each of the men, 165- pounders on earth, weighed something over 25 pounds on the moon.

ARMSTRONG BEGAN the rock picking on the lunar surface. Aldrin joined him using a small scoop to put lunar soil in a plastic bag.

Above them, invisible and nearly ignored, was Air Force Lt. Col. Collins, 38, keeping his lonely patrol around the moon for the moment when his companions blast off and return to him for the trip back home. Collins said he saw a small white object on the moon, but didn’t think it was the spacecraft. It was in the wrong place.

Back at Houston, where the nearly half-moon rode the sky in its zenith, Mrs. Jan Armstrong watched her husband on television. “I can’t believe it is really happening,” she said.

Armstrong surveyed the rocky, rugged scene around him. “It has a stark beauty all its own,” he said. “It’s different. But it’s very pretty out here.”

THEY TOOK pictures of each other, and Aldrin shot views of the spacecraft against the lunar background.

In a world where temperatures vary some 500 degrees, from 243 degrees above zero in sunlight, to 279 below in shadow, the men in the spacesuits felt comfortable.

Aldrin reported, ‘In general, time spent in the shadow doesn’t seem to have any thermal effects inside the suit. There is a tendency to feel cooler in the shadow than out of the sun.”

The sun was a problem for vision. “I have so much glare from the sun off the visor that when I go into shadow, it takes a while for my eyes to adjust,” Aldrin said.

The dust, too, was unusual. “The color of my boot has completely disappeared into… I don’t know how to describe it — a kind of cocoa has covered my boot.”

In spite of the dust, they raised as their rocket flame churned the surface from as high as 40 feet, there was no discernible crater below the descent engine, they reported.

Nearly seven hours before Armstrong stepped onto the moon’s surface, he had voiced man’s first words from the moon: “Tranquillity base here. The Eagle has landed.”

“Fantastic,” exclaimed Astronaut Collins, piloting the Columbia mother ship on its lonely orbit 69 miles above the moon.

It was quick action by Armstrong that–a few minutes earlier–had averted a tragic ending to the moon landing. As Eagle neared the lunar surface, its computerized automatic pilot sent the fragile ship toward a field of rocks and boulders in the projected landing site in the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

ARMSTRONG grabbed control of his ship, steered it clear of certain disaster and put it down 4 miles beyond the original standing point.

It was a costly maneuver. It cut the available fuel short. When it landed, Eagle had barely 49 seconds worth of hovering rocket fuel left, less than half of the 114 seconds worth it was supposed to have.

“The auto-targeting way taking us right into a football field-sized crater with a large number of big boulders and rocks,” Armstrong said. “And it required us to fly manually over the rock field to find a reasonably good area.”

THEY LANDED JUST NORTH of the moon’s equator. In the original landing site, Armstrong said there were “extremely rough craters and a large number of rocks. Many of them were larger than 10 feet.”

The world thrilled to the moment. London’s Trafa!gar Square rang with cheers and screams of delight. Men and women, some carrying babies, jammed through the fountains and saw the news of the touchdown flashed on a giant screen. “Thank God they’ve made it,” said one woman.

At New York City’s Kennedy Airport, 2,500 clustered around television screens at the International Arrivals Building. And at Yankee Stadium, 35,000 fans watching the Yankees and Senators saw the news on the scoreboard: “They’re on the moon.” Everything stopped as the stadium filled with cheers. Then they fell silent for a moment of prayer, then sang “America the Beautiful.”

OUTSIDE HER flag-draped brick Colonial home at Wapakoneta, Ohio, where Armstrong was born and learned to fly, his mother, Mrs. Stephen Armstrong said, “I hope it will be for the good of all mankind.”

President Nixon, who watched the news of the landing from his working office in the Executive Office Building next door to the White House, sent his personal congratulations.

It was after the landing that Aldrin radioed from the Eagle on the moon a message to the people of Earth:

“This is the LM (lunar module) pilot. I’d like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening, wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events oi the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.”

It was just seconds before 4:18 p.m. (EDT) that Armstrong and Aldrin touched down safely in a swirl of dust on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

ARMSTRONG, A CIVILIAN, radioed the first words from the surface:

“Contact light. Okay, engine stopped. ACA at a descent. MODE control both auto. Descent engine command override off. Engine arm off. 413 is in.

“Houston. We uh . . . Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

The Houston Centro] Center referred to the Eagle on the moon as “Tranquillity Base.”

The space agency said the estimated landing time was 4:17:42.

ARMSTRONG REPORTED that the automatic guidance system was taking “us right into a football field size (area) of craters.” Armstrong ‘said he took over control manually over the rock field “to find a reasonably smooth area.”

“It looks like a collection of just about every variety — shapes, angularities, granularities, just about every variety of rocks you can find,” Aldrin reported.

Aldrin said there didn’t seem to be much color, but he said some rocks in view “looks as though they will have some interesting color to them.”

“This one-sixth G (gravity) is just like an airplane,” Arm-strong said.

When told by ground control there were lots of smiling faces around the world, Armstrong replied, “There are two of them up here.”

Armstrong’s heart rate was 110 at the time the descent started and it shot to 156 beats per minute at touchdown. The rate quickly settled down to the 90s.

There was no medical data on Aldrin.

Collins talked to “Tranquillity Base” and said, “It sure sounded great. You guys did a fantastic job.”

“Thank you,” replied Armstrong. “Just keep that orbiting base ready for us.”

“WILL DO,” replied Collins in Columbia.

“You’re looking good there,” said Ground Control.

“We’re going to be busy for a minute,” Armstrong said moments after touchdown.

“Very smooth touchdown,” said Aldrin.

Ground control reported at 4:32 p.m. (EDT) that Eagle’s systems looked good after the landing. This was important, because the ship must carry the astronauts back into orbit today.

After giving their landing craft’s systems a quick check, Armstrong and Aldrin simulated a countdown to make sure everything was set for their blastoff today.

Armstrong reported there were several alarm signals during the final minutes of the descent and this took his attention from looking for landmarks that would identify Eagle’s precise touchdown point.

“You might be interested to know that I don’t think we noticed any difficulty to adapt to one-sixth G,” Armstrong reported. He said it seemed natural to move about in the gravity one-sixth as strong as earth’s.

Armstrong reported he could see “literally thousands of little 1 and 2-foot craters around the area.

“We see some angular blocks in front of us.”

He said there was a hill that appeared to be a half mile or a mile away. ;

At 4:38 p.m. (EDT) Earth Control radioed up landmark information in an attempt to help the pilots precisely locate their touchdown site.

Ground control told Collins that Eagle bird landed “just a little bit long.”

THE LANDING SITE was an oval, 8 miles long and three miles wide.

Computer calculations before launch gave them a 99.9 percent chance of landing in it.

“I’d say the color of the local surface is very comparable to that we observed from orbit at this sun angle, about 10 degrees of the sun.”

SHORTLY AFTER 4 p.m., Armstrong and Aldrin shoved themselves out of a low-sweeping orbit and into their final descent toward the moon, aiming for the southwest edge of the lunar Sea of Tranquillity.

At 4:05 p.m., just seconds before the landing engine was fired, the Eagle was 46,000 feet above the moon.

Armstrong then fired the big engine, throttling it to 10 percent of its total thrust.

Seconds after Armstrong reported 10 percent thrust, communications were interrupted briefly by the thrust.

Then the astronauts reported again to earth. There were no problems.

“Eagle, we’ve got you now. It’s looking good,” said ground control.

Armstrong and Aldrin started their final approach about 300 miles east of the landing site, dropping toward it from the 9.8-mile low point of an orbit that had carried them away from Collins in the command ship Columbia.

They fired their descent engine behind the moon to enter this low-sweeping orbit, designed to place them in position to drop on down to the surface. They had separated from “on and the command ship Columbia at 1:47 p.m. (EDT). ,

At 3:48 p.m., (EDT) Armstrong and Aldrin emerged from behind the moon in an orbit that would take them to within 9.8 miles of the moon’s surface.

“Listen, babe, everything’s going just swimmingly, beautiful,” Collins reported as the command ship first appeared around the near side of the moon. He said the landing craft was “coming along” behind.

RADIO SIGNALS were received from Columbia at 3:47 p.m. (EDT) or the 14th orbit. Two minutes later, Eagle’s signals were received by ground stations. Columbia was flying ahead of Eagle, which was slowing down.

At 3:55 p.m. (EDT), Eagle was 14 miles above the moon. and descending.

“Columbia, Houston, we’ve lost all data with Eagle.” Ground Control said during a momentary loss of communications while antennas were being switched.

Then Armstrong radioed earth without any sign of the static that interrupted radio communications a few seconds earlier.

Armstrong reported that the firing had dropped Eagle into the proper orbit.

“Looks great,” Ground Control said. ;

“We’re off to a good start.” Flight Director Kranz told controllers. “Play it cool.”

Aldrin reported at 3:56 p.m. (EDT) that Eagle’s vital Steerable antenna was “picking up oscillations.”

At 3:58 p.m., controllers reported Eagle’s emergency guidance system was operating normally. This would be used to abort the final descent and steer the astronauts back into a safe lunar orbit if trouble developed.

AT 4 P.M., EAGLE was advised to rotate the spacecraft 10 degrees to improve communications with earth.

“Eagle, Houston, if you read, you are go for a powered descent,” Ground Control radioed the landing pilots at 4 p.m. (EDT).

“Roger, understand,” replied Armstrong.

“Mark, 3:30 to ignition,” Ground Control radioed the astronauts prior to the start of their descent.

The astronauts coolly read off switch positions gauge readings to each other in the final minutes before firing their landing engine the final time.

AT 4:07. P.M. (EDT), the ship’s altitude was 47,000 feet above the moon.

Armstrong then reported that he was reading “a little fluctuation” in a voltage indicator. But Ground Control said the Eagle continued to look good.

“You are go to continue powered descent,’ Ground Control radioed the landing astronauts, 40,000 feet above the moon at 4:09 p.m.

At 33,500 feet, Ground Control reported the ship was receiving good data from its vital landing radar.

“At 27,000 feet, “We’re still go,” Mission Control reported at 4:11 p.m.

“It looks good now,” Armstrong reported.

The ship was at 16,300 feet at 4:12 p.m. (EDT).

“You are go for landing,” the pilots were told two minutes before landing.

“2,000 feet,” said Armstrong.

As the tension-packed seconds ticked off the countdown clock, the Eagle’s retro-rockets continued to slow the descent of the lunar lander. By the time the craft was hovering close to the landing target in the Sea of Tranquillity, its descent had been slowed to less than 3 feet per second — for an impact equivalent to a man jumping off a desk.

Space Center recording of the radio contact with Armstrong and Aldrin dramatically reflects the mathematical precision of the last moments before touchdown:

ALDRIN — 35 degrees, 5 degrees, 700 fect. . . 30 degrees -.. 540 feet… 400 feet down at nine . . . 250 feet down at 4… velocity … 47 forward… 70… 50 down at 24. 19 Forward. Altitude velocity light 214 down. 13 Forward … 200 feet 4144 down.

514 Down. 150 Feet. 544 Down. 9 Forward. 120 Feet. 100 Feet. 3144 Down, 9 forward. 75 Feet and looking good down . 6 Forward. 60 Seconds. Down 214 … Forward… forward … 40 feet down 214. Kicking up some dust. 4 Forward, 4 forward drifting right a little…

ARMSTRONG — Tranquillity Base here. Eagle has landed!

DUKE — Roger. Copy you down. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue here.

DUKE — You’re go for stay one, go for stay one.

ALDRIN — Looks like we’re…

DUKE — Eagle, you’re stay for one and we see you venting the ox (oxygen).

COLLINS — Houston, do you read Columbia high gain?

DUKE — Roger, we read you, Columbia. He has landed at Tranquillity Base. Eagle has landed.

COLLINS — Yeah, I heard the whole thing. Good show. Fantastic.

While Armstrong and Aldrin methodically moved Eagle closer and closer to its historic lunar landing, Collins –the only Apollo-11 crewman not headed for a moon touch-down–piloted his Columbia command ship on a lonely orbit around the moon.

It was at 1:47 p.m., on the dark side of the moon with no earth radio contact, that Armstrong pushed the starter button on Eagle’s dashboard, breaking the lunar lander away from the mother ship.

Collins at that point pulled his Columbia command ship 2 miles away from the Eagle, getting out of the way so his comrades could start down toward the moon’s surface.

Once the separation was completed, Armstrong turned on the Eagle’s descent engine in a blast to slow it from its 3,651.6- miles-per-hour orbital speed. It was at 2:12 pm. that the peri- lous descent began.

“See you later,” Aldrin told Collins in the command ship just before he fired a short burst from his control rockets and widened the gap between the two craft.

“That separation maneuver was performed as scheduled,” reported a control center spokesman at 2:14 p.m. (EDT).

“You’re going right down U.S. 1, Mike,” Armstrong radioed Collins as he gradually moved away in Columbia.

Apollo 11’s mission plan

Every hour of the Apollo 11 mission had a different page with the flight plan for that specific 60-minute period. Here you can take a look at what the astronauts were reviewing as they prepared for the actual landing on the moon — 102 hours and 47 minutes after they were launched from Earth. (There were a total of 185 pages in the plan.)

NASA via the National Archives and Records Administration – July 20, 1969

The abbreviations seen on the plan are as follows:

- CSM = Command Service Module

- LM = Lunar Module

- MCC-H = Mission Control Center-Houston

- CMP = Command Module Pilot (Mike Collins)

- CDR = Commander of the Mission (Neil Armstrong)

- LMP = Lunar Module Pilot (Buzz Aldrin)

Apollo 11: The speech Nixon would have given ‘in event of moon disaster’ (1969)

As a contingency, White House speechwriter William Safire was asked to craft a statement that then-President Nixon could read in the event of a disaster.

Thankfully, of course, the men returned safely (see the story here: The first walk on the moon) and the speech was never needed. Instead, it was safely tucked away in the National Archives and preserved as a bit of history that never happened.

For President Nixon, in case of Apollo 11 disaster

To: H.R. Haldeman

From: Bill Safire

July 18, 1969

IN EVENT OF MOON DISASTER:

Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.

These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.

These two men are laying down their lives in mankind’s most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.

They will be mourned by their families and friends; they will be mourned by their nation; the will be mourned by the people of the world; they will be mourned by a Mother Earth that dared send two of her sons into the unknown.

In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.

In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.

Others will follow, and surely find their way home. Man’s search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts.

For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.

PRIOR TO THE PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT:

The President should telephone each of the widows-to-be.

AFTER THE PRESIDENT’S STATEMENT, AT THE POINT WHEN NASA ENDS COMMUNICATIONS WITH THE MEN:

A clergyman should adopt the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to “the deepest of the deep,” concluding with the Lord’s Prayer.

One Response

The moon landing was one of my very earliest memories. I remember not only the landing itself and the wall-to-wall TV coverage, but all the hype surrounding it and the grown-ups around me obsessed with it. Gulf gas stations were giving away paper models of the lunar module as well as books about space for kids.