But the path from a small feast in Plymouth to a federally recognized tradition was anything but straightforward.

The 1621 gathering that inspired it all has long been mythologized into something cleaner and more harmonious than it really was. The Pilgrims, after a devastating first year in New England, marked their survival with a three-day event that included the Wampanoag tribe.

It was part celebration, part diplomacy. The food was local and practical — venison, corn, shellfish, and wild fowl — nothing like the standardized menu we know today. There was no expectation of tradition, because this feast was really about staying alive and keeping the peace.

The version of events that stuck, though, looks a lot more like the painting featured at the top of this article. Created in 1912 by artist J.L.G. Ferris, the image has all the makings of a tidy American origin story. The Pilgrims are clean and composed, the Native people are calmly seated, and the mood is harmonious. It’s an image built for textbooks, television, and holiday cards… not historical accuracy.

But the rebranding worked. Paintings like this one by Ferris helped shape the public’s idea of Thanksgiving — framing it as a peaceful meal that kicked off a long tradition, instead of a single, complicated moment in early colonial history. Pilgrim hats and turkeys became icons.

Over the next couple of centuries, Thanksgiving celebrations popped up mostly in New England, declared sporadically by governors and occasionally by Presidents. George Washington supported the holiday, but Thomas Jefferson openly opposed it, citing the importance of separating church and state. Despite early momentum, the idea of a national Thanksgiving languished for decades, with regional observances that looked very different from what most Americans now expect.

That changed thanks to the efforts of writer and editor Sarah Josepha Hale. She spent years campaigning for a unified national holiday, and finally got President Abraham Lincoln on board in 1863. In the middle of the Civil War, Lincoln saw value in a day of reflection and declared the last Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day.

Even after that, the date wobbled a bit — including a brief shift during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration that caused enough confusion for Congress to step in and fix it on the fourth Thursday of November in 1942.

As the country modernized, Thanksgiving kept changing. The meal became more standardized, turkey took center stage, and newer traditions like parades and football were added. But the core idea has stayed the same: Taking a moment to appreciate what we have.

Below, we’ve pulled together a collection of vintage photos, prints and original articles that show how Thanksgiving has been explained, celebrated, and remembered through the decades.

Tracing America’s Thanksgiving history for three centuries (1955)

From The Curious Story of Thanksgiving (Aramco World, Vol 6, No 10) November 1955

The most typically American holiday — Thanksgiving Day — a time for family reunions, feasting, dancing, football games, turkey raffles and solemn religious observance has been America’s most controversial holiday. Its 334-year history is filled with argument, confusion, and impassioned oratory.

Celebrations continued for 320 years on a helter-skelter basis before it achieved national recognition and became a legal national holiday.

Harvest time has been a season of festivals and thanksgiving over the world from the day man reaped his first bountiful crop from a yielding earth. Every country has its own version of harvest celebration, and all of them are joyous, and, in a manner, religious.

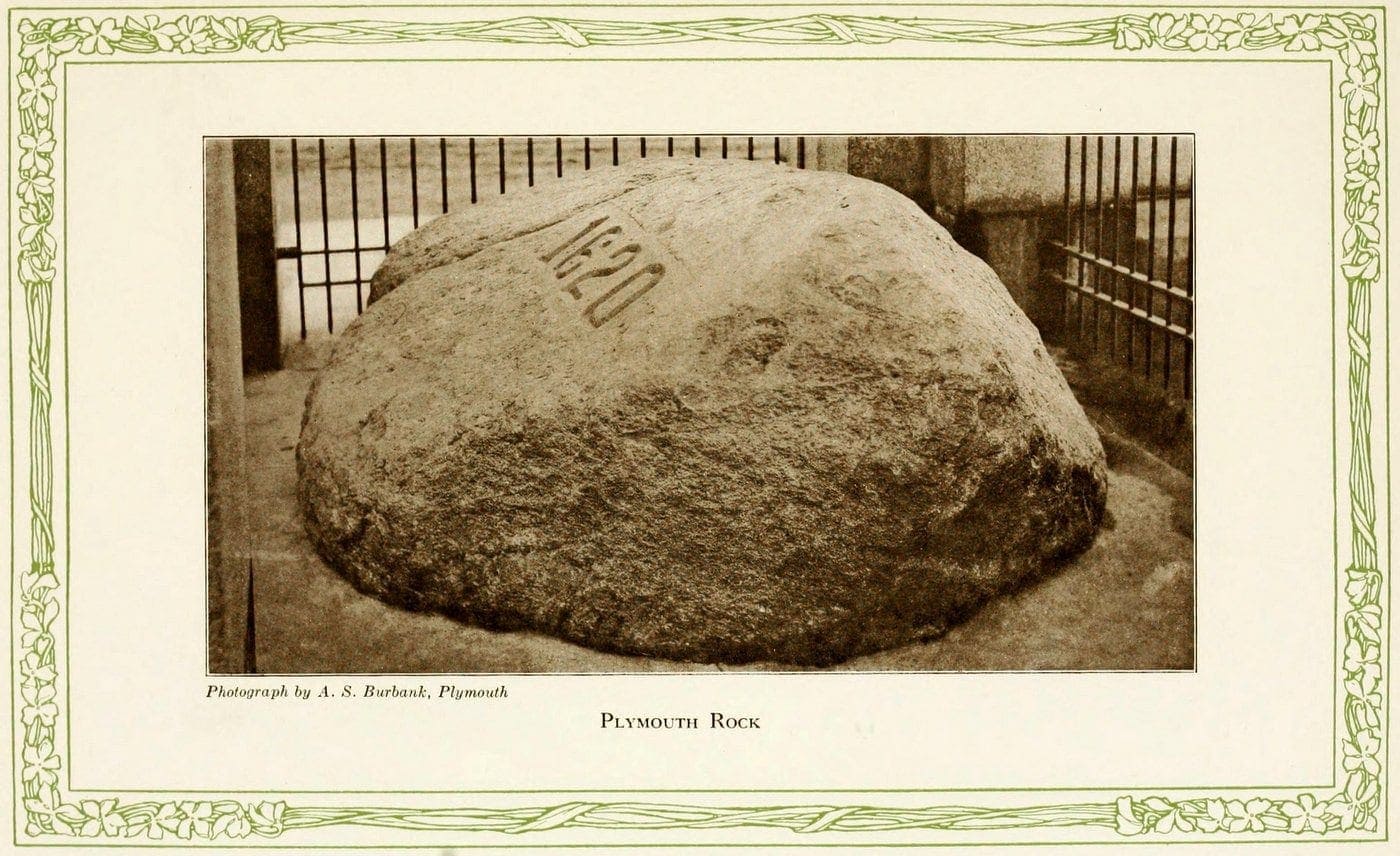

America’s Thanksgiving history started with the Pilgrims

When the 102 Pilgrims stepped on the Mayflower to settle in Plymouth, they didn’t expect that a year later, their number would be diminished by half. After a harrowing winter and a fairly good summer, the fifty-one remaining Pilgrims reaped a big harvest — their first in the New World.

To celebrate this event, Governor William Bradford proclaimed a three-day feasting and sporting holiday. Ninety friendly Indians were invited, and the emphasis was placed on friendship, food, fun and the “exercise of arms.”

Though it may cause some consternation among modern-day celebrants who have lived with the idea that the first Thanksgiving Day was a turkey, cranberry sauce and mince pie affair, the truth is that the feast menu was made up of boiled eels, venison, wild duck, clams, mussels, cornbread and plums — all washed down with sweet wine.

The Pilgrims knew about mince pie, but objected to it because it was a favorite dish of the Stuart kings, and symbolized English Christmas, an unhappy memory.

The three-day festival was a great success. Friendship between the Indians and the Pilgrims was solidified, and everyone seemed happy. Yet it was fifty years before the Plymouth Pilgrims held another Thanksgiving Day feast. No one seems to know why, although some historians assume that the presence of so many Indians discouraged a repetition.

The idea caught on with the Massachusetts Bay Puritans and the Dutch in New Amsterdam, and they decided on such a holiday nine years later. It had nothing to do with feasting, dancing, sports, or harvests — for it was held on July 8, 1630. Two years later, however, they switched to October to celebrate a fine crop. Thereafter, they held a feast every two years.

It was the Puritans who brought religious significance to the holiday. They frowned on games and drinking on a day devoted to Thanksgiving. Unlike the Plymouth Pilgrims, who were friendly with the Indians, the Puritans included in their celebrating the destruction of a large band of marauding braves a few days earlier.

For 200 years, Thanksgiving Day was strictly a New England holiday, proclaimed each year by governors and, occasionally, by Presidents. The rest of the country looked askance at this Yankee holiday, and suspiciously refused to recognize its existence.

How past presidents helped create the national Thanksgiving history

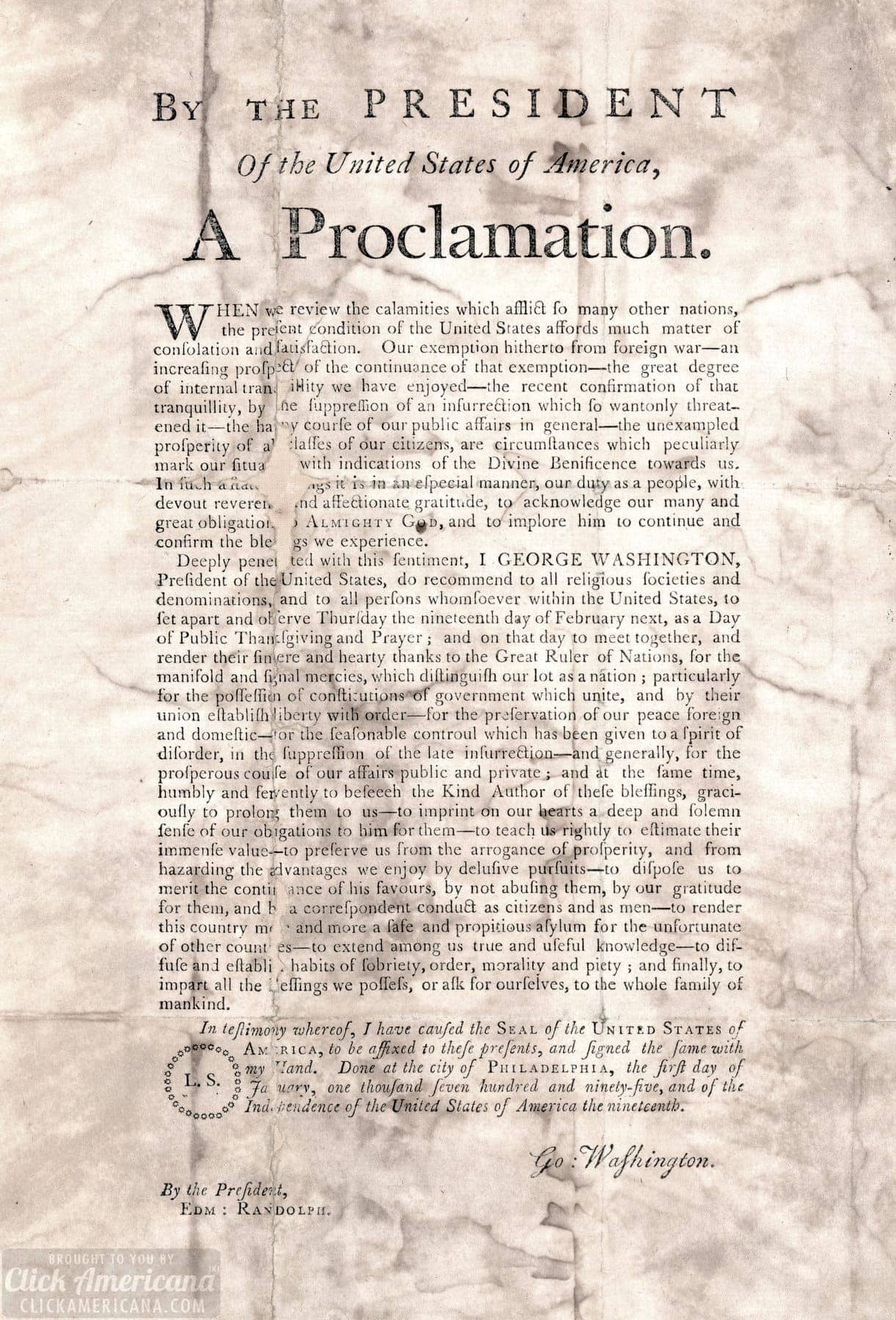

George Washington proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving for his army in 1782, granting each soldier an extra food ration and two new shirts. This helped to popularize the holiday, and many soldiers from southern states later returned to New England to celebrate Thanksgiving Day.

As President, Washington proposed the first national Thanksgiving Day in 1789, with the suggestion that the young nation give thanks for its new constitution and the end of the war.

A hostile Congress almost nullified the idea. Southern congressmen vigorously opposed it, arguing that it smacked of Yankee propaganda. A South Carolina representative claimed he didn’t enjoy copying European customs and assailed the project with a long harangue.

Despite these objections, Washington proclaimed November 26, 1789, as the first national Thanksgiving Day.

But not again for six years did he name such a day.

President John Adams, however, liked the idea and, despite a still protesting Congress, called a holiday in May 1789, and another in April 1799 — neither having anything to do with the original intent of celebrating harvests. Somewhere along the line, the joy over good crops expressed by feasting, sporting games, and dancing was almost completely lost.

When we almost lost Thanksgiving

It was President Thomas Jefferson who really dealt the holiday an almost mortal blow. He maintained that it was becoming too religious an observance, and as President, he would adhere to the proposition that the Church and State should be separated. He, therefore, refused to proclaim Thanksgiving Day during his entire administration.

New Englanders, in angry retort, continued with state-proclaimed celebrations, and one clerical critic went so far as to say in a sermon: “O Lord, endow the President with a goodly portion of Thy grace, for Thou, O Lord, knowest he needs it.”

Pressure for the holiday observance was very strong in Massachusetts, but Gov. Elbridge Gerry, a rabid Jeffersonian, found a way to circumvent it. He issued a proclamation — but it took two hours to read it before the usual church services began. By the time the order was read, most of the parishioners had scattered to their homes to cook the big dinners, and the ministers faced empty pews.

Jefferson’s attitude was not a solitary protest — actually, it lasted sixty years, as President after President followed suit. It appeared that Thanksgiving Day as a national holiday was doomed. But in 1855, three states in the South made a dramatic about-face: Georgia, Texas, and Virginia decided to mark the holiday.

Thanksgiving history: When the celebration became a national holiday

Sara Josepha Hale, who wrote “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” was the greatest single influence in establishing the day as a national legal holiday. As editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most famous women’s magazine of the time, she wrote impassioned articles, editorials, letters and appeals, imploring every President to act on behalf of a national Thanksgiving Day.

In 1863, her appeal finally caught the fancy of President Lincoln. In a year that saw the bloody battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Lincoln responded by issuing his first Thanksgiving Day proclamation — marking the actual start of our modern observance of the holiday on the last Thursday in November.

Curious reasons for celebrating the day were given throughout its history. President Madison cited the victory in the Battle of New Orleans; Lincoln was thankful that no foreign power had attacked the Union during the Civil War; Grant blessed the huge influx of immigrants in 1876; and Hayes rejoiced because there were no shipwrecks or major disasters. Grover Cleveland was the first President to refer to the “reunion of families” in his proclamation.

President Theodore Roosevelt signing his 1902 Thanksgiving Proclamation

Finding the Thanksgiving holiday as home on the fourth Thursday of November

But Thanksgiving Day’s rough voyage toward national acceptance was still to face the rapids of national discontent.

In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the request of businessmen all over the country, who wanted more shopping time between Thanksgiving and Christmas, suggested that the day be proclaimed on the third Thursday in November. This change, actually, was not such an innovation, since the date had shifted continuously through eight months in a period of 300 years.

The nation, however, broke into loud protest, and twenty-three states refused to abide by the new date. In fact, to appease all sides, Texas and Colorado held two Thanksgiving Days.

After three years of confusion and protest, President [Franklin Delano] Roosevelt, in 1942, agreed to return to the old date. Congress then passed a resolution legalizing the fourth Thursday in November as national Thanksgiving Day.

The fall harvest at the center of the Thanksgiving history

Some of the traditions of this eventful day have strange origins. While retaining its religious significance, Thanksgiving Day is still, primarily, a harvest celebration. The traditional football games, the raffles, turkey shoots, and the feasting are all reminders of the original joyous celebration of a bountiful crop, the testing of skills and swordplay of the early celebrants.

This is true of harvest festivals all over the world. Through hundreds of years, European countries had developed special rituals to celebrate this season.

In Austria, November 15 is known as St. Leopold’s or Goose Day. Traditionally, huge goose dinners mark the beginning of the new wine season, and people travel to the Klosterneuburg Abbey (built in the 12th Century) to slide down the great 12,000-gallon wine cask in the festive ritual of good luck.

Feasting and drinking are the marks of the great October Festival held each year at Munich, Germany. Many countries, such as Czechoslovakia, use the corn maiden as the traditional harvest symbol. Field workers fashion a great wreath of corn and flowers, and the woman who binds the last sheaf is called “baba.”

The wreaths and babas become the center of celebrations in all villages, and there is widespread merrymaking.

In China, the 15th day of the Eighth Moon is called the Moon Festival, marking the end of the harvest season, and one of the most joyous events in the Chinese year. All activity centers upon the moon, which influences the crops. Candies and cakes are baked in the shape of the moon, while music, feasts, and games make up the day.

The turkey, the familiar symbol of our own holiday, was originally a wild bird known to Mexicans and Central Americans. Early Spanish explorers took the bird to Europe, and it made its way to Turkey, where it was domesticated. Finally, many years later, it found its way back to North America with the name of “turkey.”

Yet the strangest twist of all is that the only country in the world where a national harvest festival day is a legal holiday through an act of Congress is the United States — the mightiest industrial nation on earth.

One Response

das Ernte Dankfest ist in Deutschland von Jeher ein kostumbre und ist von Europa nach Amerika gebracht worden und nicht andersrum , genauso mit dem Hallowin ,ist von Europa nach Amerika gebracht worden . Und so fiele andere Dinge … !