The history of the California Gold Rush of ’49: How gold was first discovered

John A Sutter, a native of Switzerland, and formerly an officer of the Swiss Guards of Charles X of France, came to the United States in 1833, and settled in Missouri. There he remained till 1839, and then made the long and difficult journey across the plains and mountains to Oregon.

Thence he went to the Sandwich Islands [Hawaii], and finally to California, where he obtained the liberal grant of forty square miles of land in the Sacramento Valley. His disposition to rove was now satisfied, and he established himself on this princely domain.

With the aid of a few foreigners and the neighboring Indians, whom he conciliated by kindness and taught to labor, he built a spacious dwelling after the original California style, which was dignified with the name and had something of the character of a fort.

Here he lived most of the time alone, except for the company of his Indian retainers, who occupied burrows and huts in his neighborhood, and who labored in his fields and acted as herdsmen of his cattle.

His fields yielded an abundance to supply the wants of his establishment and his native dependants, and his cattle multiplied so that, when Fremont first enjoyed his hospitality and obtained from him supplies, he was a wealthy proprietor of the old Californian type.

An accidental discovery

In 1848, Mr Sutter built a saw-mill on the south fork of the American River. Two Americans who were employed in this work, in order to hasten the excavation of the race, turned a powerful current of water through it, and when the sand thus washed out was exposed by the subsidence of the water, it was seen to contain numerous shining particles, some of which were collected, and appeared to be gold.

Further examinations developed the fact that the valley was rich in these deposits, and upon being examined by competent judges, they were pronounced to be really gold.

At first, the reported discovery of gold was received with incredulity by the people in the towns along the coast; but when the news was confirmed by an exhibition of some of the precious metal from the “placer,” the excitement was intense, and all who could hastened to share in the spoil.

The Rev. Walter Colton, a chaplain in the United States Navy, at that time held the office of alcalde, or mayor, of Monterey, having been elected by the people of the town some time after its capture by the American squadron.

In his journal of “Three Years in California,” he gives an amusing account of the reception of the news of the discovery and its effects on the population.

“A straggler,” he says, “came in from the American Fork, bringing a piece of yellow ore weighing an ounce. The young dashed the dirt from their eyes, and the old from their spectacles. One brought a spyglass, another an iron ladle; some wanted to melt it, others to hammer it, and a few were satisfied with smelling it. All were full of tests; and many, who could not be gratified in making their experiments, declared it a humbug.

“One lady sent me a huge gold ring, in the hope of reaching the truth by comparison; while a gentleman placed the specimen on the top of his gold-headed cane and held it up, challenging the sharpest eyes to detect a difference. But doubts still hovered on the minds of the great mass. They could not conceive that such a treasure could have lain there so long undiscovered. The idea seemed to convict them of stupidity.”

To settle the question of the truth of the reports, the alcalde sent a trusty messenger to the American Fork to learn the facts. In a fortnight, this man returned with specimens of the gold.

“As he drew forth the yellow lumps from his pockets, and passed them around among the eager crowd, the doubts, which had lingered till now, fled. All admitted they were gold, except one old man, who still persisted they were some Yankee invention, got up to reconcile the people to the change of flag. The excitement produced was intense, and many were soon busy in their hasty preparations for a departure to the mines.

The stampede to join the California Gold Rush

“The family who had kept house for me caught the moving infection. Husband and wife were both packing up; the blacksmith dropped his hammer, the carpenter his plane, the mason his trowel, the farmer his sickle, the baker his loaf, and the tapster his bottle.

“All were off for the mines; some on horses, some on carts, some on crutches, and one went in a litter. An American woman, who had recently established a boarding-house here, pulled up stakes and was off before her lodgers had even time to pay their bills. Debtors went of course. I have only a community of women left, and a gang of prisoners, with here and there a soldier who will give his captain the slip at the first chance.”

This wholesale departure of all sorts of people proved not a little inconvenient and annoying to those who were obliged to remain.

Mr. Colton soon had reason to complain that the gold fever had “reached every servant in Monterey; none are to be trusted in their engagement beyond a week, and as for compulsion, it is like attempting to drive fish into a net with the ocean before them.

General Mason, Lieutenant Lanman, and myself, form a mess; we have a house and all the table furniture and culinary apparatus requisite; but our servants have run one after another, till we are almost in despair; even Sambo, who we thought would stick by from laziness, if no other cause, ran last night; and this morning, for the fortieth time, we had to take to the kitchen and cook our own breakfast. A general of the United States army, the commander of a man-of-war, and the alcalde of Monterey, in a smoking kitchen, grinding coffee, toasting a herring, and peeling onions! ”

A few days later the alcalde writes: “Another bag of gold from the mines, and another spasm in the community. It was brought down by a sailor from the Yuba River, and contains a hundred and thirty-six ounces… My carpenters at work on the schoolhouse on seeing it threw down their saws and planes, shouldered their picks, and are off for the Yuba. Three seamen ran from the Warren, forfeiting their four years’ pay; and a whole platoon of soldiers from the fort left only their colors behind.”

In the course of three months from the first discovery of gold some of the early seekers for the precious ore began to return to the towns with their gains, and Mr. Colton relates a characteristic anecdote which illustrates the lavish manner in which the lucky miners expended their quickly acquired wealth, an early example of what was very soon a common habit.

“My man Bob,” says Mr. Colton in his journal, ” who is of Irish extraction, and who had been in the mines about two months, returned to Monterey about four weeks since, bringing with him over two thousand dollars as the proceeds of his labor. Bob, while in my employ, required me to pay him every Saturday night in gold, which he put into a little leather bag and sewed into the lining of his coat, after taking out just twelve and a half cents, his weekly allowance for tobacco.

“But now he took rooms and began to branch out; he had the best horses, the richest viands, and the choicest wines in the place. He never drank himself; but it filled him with delight to brim the sparkling goblet for others.

“I met Bob today, and asked him how he got on. ‘O, very well,’ he replied,’ but I’m off again for the mines.’

‘How is that, Bob? You brought down with you over two thousand dollars; I hope you have not spent all that; you used to be very saving; twelve and a half cents a week for tobacco, and the rest you sewed into the lining of your coat.’

‘O, yes,’ replied Bob, ‘and I have got that money yet; I worked hard for it, and the de’il can’t get it away; but the two thousand dollars came easily, by good luck, and has gone as easily as it came.’ ‘

Such was the effect of the discovery of gold on the people of California, native and foreign. The possession of the country by the United States had opened it to immigration, and already many Americans had found their way thither, besides those who were there before the war, and most of them had rushed to the placers at the first announcement of the existence of gold.

But when the news of the discovery reached the States and was transmitted over the world, then began a most remarkable immigration and a new settlement of California. Gold- seekers came from Mexico and the western coast of South America when reports of the discovery reached those countries, and among them many lawless adventurers were the first to hasten to the mines. But the discovery awakened the widest interest in the United States, from which an immense emigration speedily commenced and continued for years.

A long and difficult journey to reach California

Great numbers of men from all parts of the country joined the caravans, great and small, which, starting from the West, travelled across the plains and through the mountain passes which Fremont had discovered and described, making the long and toilsome journey not without frequent hardships and mishaps, and occasional attacks of bands of hostile Indians.

The large caravans were too formidable for the savages to venture an attack, but smaller companies, following the trail of the larger, or stragglers who imprudently tarried in the rear, did not always escape. There was no state in the Union, and scarcely a town of any considerable size west of the Alleghenies, that had not its representatives among these travelers across the plains; and many a farm even on the fertile prairies of the West was deserted, and the long and wearisome journey endured, for the alluring prospect of gathering golden scales and nuggets directly from the soil of El Dorado.

Toiling over the Sierra Nevada, these immigrants descended into the valleys of California, most of them seeking the placers, where, with shovel, pick and pan, they could wash the glittering ore from the earth; but some, quite as shrewd if not as eager, preferred to gather in the fruits of the miners’ labor by a profitable trade in the necessary supplies and the ill-chosen luxuries of the multitude of gold-hunters.

In the Atlantic ports, there was a new and universal bustle. The great cities furnished numerous adventurers, who, unsuccessful at home, were ready to try their luck in this new field; and the chances of rapidly acquiring wealth induced many to forsake the slower methods of regular industries for the hardships and the more laborious toil of the miner’s life.

Men associated in companies and bought or chartered old vessels and new to transport themselves and their outfit by the long voyage around Cape Horn to the land of golden promise. Immense clipper ships were built to engage in the California trade, and were laden with goods for this new and profitable market and with passengers bent on making their fortunes.

Lines of steamers were established to run to the Isthmus of Panama, where merchandise and passengers were transported across the land and carried thence in other steamers on the Pacific; and to facilitate travel by this route, which saved a long and stormy passage around the Horn, a railroad was soon constructed across the isthmus.

California was thus connected by a comparatively speedy route with the Atlantic States; but in after years even this was of secondary importance, and seemed wearisomely long w r hen the Atlantic and Pacific were united by a band of iron rails across the continent, and the traveler spent scarcely more than a week between New York and San Francisco.

San Francisco: The Gold Rush’s boom town

When Fremont first raised the flag of independence in California, and thus secured its possession to the United States, there was no town and only a few dwellings on the shores of the magnificent Bay of San Francisco. Where the city now stands, a dozen adobe houses were all that marked a settlement, and four miles away was the once prosperous Mission of San Francisco.

But after the discovery of gold, the numerous ships, which came in ever-increasing numbers, entering the “Golden Gate” found a better harbor than elsewhere on the coast. Here the passengers landed and the ships were unloaded, and while the bay was whitened with sails there sprang up on the land, as if by magic, a multitude of tents and board and canvas houses, where the miners prepared for their future labors, and the traders speedily commenced to dispose of their wares.

Thither came the successful gold- hunters to purchase supplies and spend their quickly found treasure, and thither came ships from all quarters of the world with more immigrants and more supplies. More advantageously situated than the old Californian towns for this new commerce, San Francisco, from a collection of tents and shanties, quickly grew to a more permanent and substantial condition, with a population and trade increasing with marvelous rapidity.

But San Francisco was not the only place where miners, traders and adventurers congregated, and with their tents and temporary buildings commenced settlements which soon grew to be populous and thriving towns. Sacramento, Stockton and other places in the gold regions were thus founded, and became centers to which the miners resorted for supplies and “prospectors” for information.

Storehouses, refreshment saloons, lodging-houses, gambling-dens, and a few mechanics’ shops, all of a primitive construction, formed the beginning of these towns, and the keepers of these establishments comprised the more permanent population, while a crowd of transient sojourners on their way to or from the “diggings,” miners purchasing supplies for their camps, keen speculators watching to secure promising “claims,” adventurers in pursuit of nothing definite, and gamblers ready to prey upon the successful gold-hunters, crowded the prospective streets of the embryo cities, creating an ever-increasing demand for goods and accommodations.

The wealth of the mines was poured into these towns, and with their rapid growth they assumed a more substantial appearance.

How the miners tried to find gold

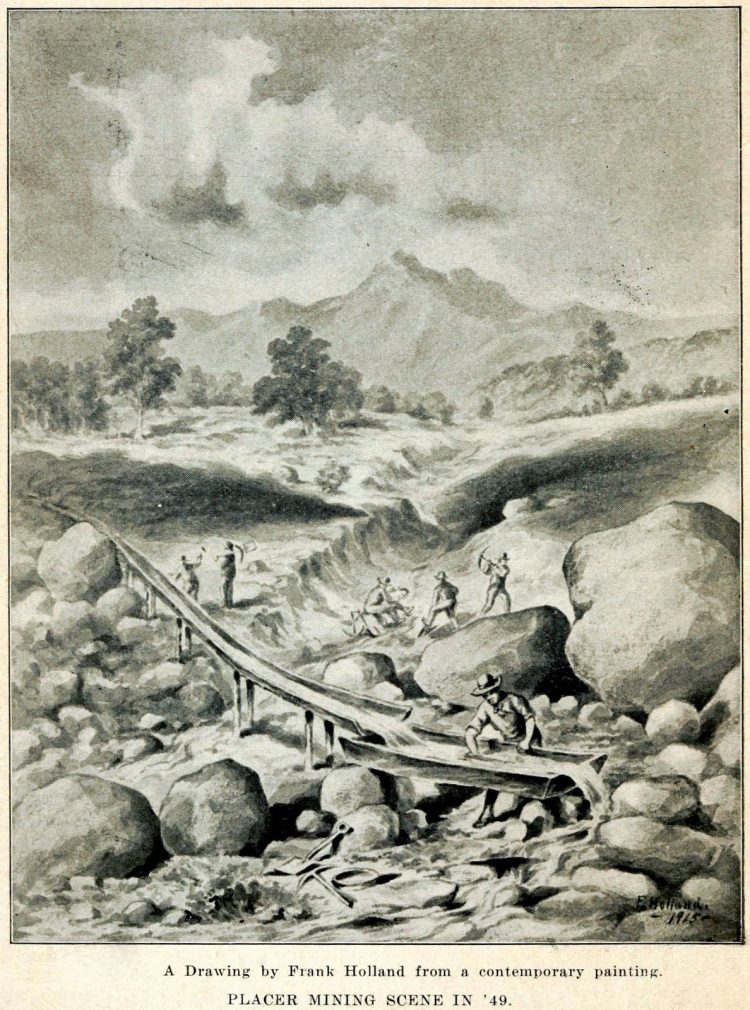

Meanwhile in the valleys of the rivers where gold was first discovered, and of their tributaries, the gold-hunters, singly or in companies, were busy with pick and shovel, cradle and pan, digging and washing the treasure-bearing soil, turning the waters from their natural bed, constructing flumes and various ingenious and inexpensive contrivances to extract the glittering grains from the worthless sand, toiling with an energy, perseverance and patience, that nothing but the hope of finding gold can inspire, and living a rough and perilous life which many of them would endure for no other pursuit.

And while these eager gold-hunters were busy in the valleys, more ambitious men were “prospecting” in the mountains for the “leads” from which the deposits in the valleys had come.

The immigration to California was not more remarkable for its numbers than the varied nationality of the immigrants. They came from all parts of the United States and the British provinces, and there was hardly a country of Europe but was represented among them. Mexico, South America, and the Sandwich Islands, furnished their quota; Australia, the gold-fields of which were then undiscovered, sent its adventurers, and China spared large numbers from its dense population. Nor were they of less varied previous pursuits.

The merchant, the physician, the lawyer, the professor, the student, the clerk, was there, as well as the farmer, the mechanic, the laborer, the mere adventurer and the idler. A few had come to gratify their curiosity or to investigate for their own or others’ advantage, but most of them simply for gain, and all with the hope of speedily realizing at least the beginning of wealth.

The outward appearance of their former avocations was left behind with the comforts or luxuries of home and the pleasures of refined society, and all were now alike in the rough garb of laborers, unshaven and unshorn, bronzed by exposure and soiled with the mud in which they labored, and associating with the rudest fellow-toiler, outwardly at least on equal terms.

Crime during the California Gold Rush

It is not surprising that among this large and mixed population there should be many lawless men and some bold criminals.

Rough and unscrupulous adventurers would drive weaker and more peaceable parties from their claims, and take possession of the results of their labor. Thieves would sometimes steal the little collection of grains and nuggets which some laborious but not over-careful miner had collected, and villains who preferred robbery to labor would violently seize the treasure of the industrious toiler, and would not hesitate to take his life also; while the Indians, led by Mexican outlaws, would occasionally venture on more general attacks.

For their own protection, the more orderly and well-disposed miners found it necessary, before a proper local government was established, to form associations in their respective neighborhoods, and organize courts for the trial of offenders. In this way, by the prompt punishment of marauders and the expulsion of the violent and dishonest trespassers upon the rights and possessions of others, offenses were diminished and life and property were rendered more secure.

Lynch law, indeed, administered with a rough sort of justice, was the most effectual if not the only protection which these communities could then have. Certain unwritten laws were recognized as the rules for the government of the conduct of all in their relations to each other, and the sure execution of the penalty for a violation of them deterred even the reckless and evil-disposed.

The rough gold-diggers could not pursue their heavy labor without some recreation, and when resting about their camp-tires they sometimes told marvelous stories, comic and tragic, or indulged in various rude games. But the amusement which attracted great numbers of them was gambling. This vice seemed a natural outgrowth of the rich results of gold-digging; the treasure quickly acquired must be speedily spent, and the chances of the gaming-table afforded the readiest and most intense excitement to be found at the mines.

Some were content occasionally to “stake their pile;” but with others, gambling was a passion which often in an hour lost for them the fruits of a week’s lucky labor, and they were forced again to content themselves for a while with digging. Keepers of gaming-tables were found wherever the miners congregated in considerable numbers, and often accumulated their “pile” more rapidly than the luckiest gold-digger.

The Gold Rush of ’49 helped California grow and grow

While many of the miners were rough and rather lawless adventurers, who considered themselves in a great measure free from the restraints of civilized communities, the continued immigration into California brought a much larger number of orderly and well-disposed people, who composed a majority of the enterprising inhabitants of the new and growing cities, and of a great part of the gold region.

The larger portion of these were from the United States, and were accustomed to the forms of popular government, and it was not long before they took measures to organize a government more in conformity with their habits and political education than the semi-military rule which the conquest of the country had rendered necessary, and to supersede the Mexican laws which were still held to be in force.

At first, they organized a provisional or territorial government in connection with the governor appointed by Federal authority. They soon afterwards framed a state constitution, and elected a complete republican government and representatives and senators in Congress.

In little more than a year from the time of the first rush to the gold region this new government was organized and set in motion; and in 1850, California, no longer an ill-governed, sparsely inhabited Mexican province, was admitted as a state of the Union.

The old regime passed away; the native Californians were swallowed up in a vastly greater new population; missions and presidios were but the remains of a departed age; the new settlement of the country had produced a change almost as marked as if the immigrants had found it inhabited only by savages, and civilization had then first supplanted barbarism.

What life was really like for the miners during the California Gold Rush: An eyewitness account

As this miner sadly wrote of the arduous journey, “All writers who have written on the subject of crossing the plains have greatly misrepresented the trip.”

Note: Photos generally from the gold rush era, not from the author of this story

California Gold Rush letter from ’49: Gold mines, North Fork

Sept 7, 1849

Dear Sir — You have, no doubt, heard before this, of my safe arrival in the gold mines of California, as I wrote my wife the next day or two after we arrived; and as the mail only departs once a month from this to the States, I have delayed writing to you so that I might the better give you such information as you would feel anxious to know.

After our arrival, our company, by mutual consent, was dissolved. Matthew Alford and Samuel Dunlop going to themselves, separately, and FPH and myself continuing together. After spending a few days in preparing for mining, we left Coloma, (where we first landed), in search of a place to commence digging for gold. We accordingly packed our mules with provisions and our implements for mining, and each of us leading a mule, we steered our course down the South Fork.

There are 3 forks to the American river, the south, north and middle forks. We would travel some three or four miles down the river, and when we would see a place that promised fair, we would unload our mules and prospect for gold until satisfied that “it would not pay,” and then we would again re-pack and travel on.

Not finding the prospect fair on the South Fork, we struck our course for the North Fork, and here we have remained, as we supposed we could do as well here as anywhere in the wet diggings.

The place where we now work is called the “Oregon Bar,” from the fact that Oregon miners first found and worked on it. Here we commenced work and have made from $10 to $50 per day. Some days yield much better than others; but none of them yield as abundantly as we expected.

There is a New York company turning the river at this bar, and when they get their dam finished, I have no doubt they will make a large amount of money. The gold is most abundant in the beds of the river, and when companies succeed in turning the stream, they almost always make fortunes.

A company about three quarters of a mile below us have just finished turning the river, and they are now getting out from six to ten pounds of gold per day, but the expenses attending an undertaking of this kind are very great. Companies for this purpose consist generally of from 15 to 50 men, and for all help they hire they have to pay from 8 to 10 dollars per day, per man, and board him; besides it is rather expensive boarding at the mines, as you will learn from a list of prices I will give you before I close.

There is quite a difference in the gold found in the wet diggings from that found in the dry diggings. The particles found in the former are very small, while those in the latter are large, weighing from fifty cents to an ounce, and sometimes much larger.

We have not been so fortunate yet as to strike on a good “streak” as they say in this country, but we expect to do so every day, and we hope to make this fall and winter a sum that will take us home a little better off than when we came here. Large fortunes are not made every day — some make fortunes in a few months, but hundreds make very little money during a whole year.

It requires hard labor to make money by digging — some are unable to stand it, while others labor hard, but from some cause or other, make comparatively nothing. The labor in mining may well be compared to that of canaling through a rocky country, for gold is always found among the rocks, and to get it you must remove them, and then, in a wooden bucket, pack your dirt to the water so as to wash it in your machine.

A bucket full of the dirt and stones will weigh about 40 pounds, and has to be carried from 5 to 25 feet, and then the path along which you have to carry it is generally over a bed of stones of various sizes, making the “road to wealth” a very rugged one. I have in this was, carried to our machine more than 3000 pounds per day, and then at night, as you may suppose, I would feel a little fatigued.

My health notwithstanding this, to me, very severe labor, is very fine, and I eat my “humble meal” with an appetite very becoming one of my profession. My bones, however, of a night, ache as though they were outfitting my frame for a severe attack of bilious fever. Men who make the most are generally those who deal in provisions, groceries and the right kind of dry goods and clothing, and we think this winter of commencing something of the kind ourselves.

It will be almost impossible to mine in the winter and rainy season, and that is the time miners spend the most money. Rents are very high in the mines, but we can in two weeks put us up a log house and in that we can trade with much success as if it were a four story brick.

I called to see one of the old Matthew Alman’s sons the other day, and he has a little establishment of this kind, and on enquiring of him about his business, he said he was doing well — that he took in from one hundred to four hundred dollars per day. I had a long talk with him about old times — while there I sold ten grains of tartar emetic to a sick man for one dollar as the fellow appeared to be poor and very sick at that.

We have now been mining about three weeks and have cleared five hundred dollars. This, in the States, would be called fair wages, but we do not look upon it in that light here. We think we ought to make at least $300 a week, and hope we shall do so in a short time.

September 14, 1849

Since writing the foregoing, we, in company with four others, have been engaged in turning the river by means of a dam partly across the river. We will complete the dam in two or three days more, and then we think we will make money very fast.

Our bar is about one hundred yards below that of the New York bar where they are doing so well; and judging from what we have seen, we think ours will yield better than theirs. They say that our prospect is much better now than theirs was when they commenced work.

Today, after we quit work for dinner, we took a large spoon and in less than half an hour dug up and washed $12 worth of gold. This has encouraged us very much, and I doubt not in my next, I shall be able to give you an interesting account of our doings on the bar.

The gold mines in this country are almost inexhaustible, but the gold is very difficult to get at and always will be so. The accounts heretofore given by writers have been greatly exaggerated. It is true that there is an abundance of gold in the mines, but the stories about men getting it in such large amounts and in so short a time is not true now, nor do I believe they ever did. But still, hard as it is to get, men can make more money here than any place I ever saw before.

The country, so far as I have seen it, is one of the most desolate, poor and unpromising countries I know of anywhere. The soil, if soil can it can be called, looks like the dust about a brick kiln, and it certainly cannot produce any kind of grain, fruit, or anything else, except the pine, the scrub oak, and some few other trees and shrubs.

It is said that grass grows well in the rainy season, which commences about the first of December, but this looks unreasonable to me as the nights are already very cool, so much so that four heavy blankets can be borne very comfortably. The country, however, is nothing, the gold is all, and this will keep people here while it lasts.

It may be a little amusing to you to know how we live in the mines, and as I am giving you rather a sketch of things than a regular historical account, I will tell you.

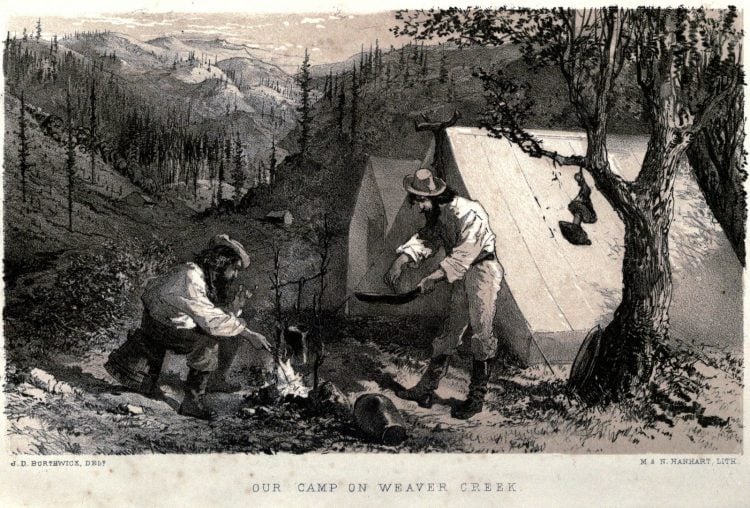

We have located under the shade of a little shrub tree. Here we dug away the rocks, scraped away the dirt so as to make it level, and then spread down our Buffalo skins and blankets. This constitutes our habitation, and the few leaves on this little tree are our only protection from the inclemency of the weather.

Our meals consist generally of fat pork, bread and coffee; sometimes, when we are lucky, we purchase a small piece of fresh meat, so as not to forget entirely how fresh meat tastes. We generally get our breakfast by sun up, and then put off to work.

After working hard until about 11 or 12 o’clock, we return to our dwelling place, and prepare for dinner, which consists of the same viands as we had for breakfast, and then, after resting an hour or two, we return again to work — then we work until night, and on returning we prepare our “tea,” which consists of the same precious articles as those we enjoyed at breakfast and dinner, and in this way we work and live; and notwithstanding we live on the diet above described, and sleep in the open air, we enjoy fine health.

The greatest trouble I have to encounter is the hard pallet on which I have to sleep. It affords very little rest to my tired bones, and instead of that sweet sleep which a clean, comfortable feather bed affords, I roll and tumble about for nearly half the night; but such is the miner’s fare, and I enjoy it as best I can.

The machine we brought with us, being one of Leavenworth’s patent gold washers, proved to be perfectly worthless and we had to throw it away. This was a severe loss to us, as it nearly broke down our team to get it here. The machines manufactured in the States are unfit for mining in this country, and those who deal in them must know it, and knowing it, they swindle those who buy them, knowingly.

Our government is greatly at fault too, in granting patents quite so liberally as they do. When an article is offered for sale with a patent attached to it, the people, of course, have some confidence in its utility, and at the same time the machine, thus patented, is worthless — and in this way, the government becomes particeps criminis in this swindling operation.

I would advise all emigrants to this country not to accept of a gold washer, if even patented by the government of the United States, should it be offered to them as a gift, as the transportation is worth more to them than the machine.

It will be out of my power to give you an account of our travels to California before I return home — I would not undertake a trip across the plains again for ten thousand dollars — indeed, I could not be hired to do so.

It is a journey of great length, of great toil and great danger — and no man can describe it as the emigrant will find it to be. Many men have died on the route and many more who are now toiling along with the hope of reaching here, will, I fear, not be able to do so.

All writers who have written on the subject of crossing the plains have greatly misrepresented the trip. Bryant’s work on California is a fancy work — well-written and well calculated to allure those who read it into difficulty if they start here on what he says. We found scarcely any truth in what he has written, and hundreds of emigrants cursed him and his work from Dan to Beersheba.

And this is true of most of the writers. They have written to make money, and they have accomplished all they desired. I have just heard from our friend Rev Mr Owen and his train. The man who saw them told me he left them about six hundred miles from here.

I have not heard from Aaron Orr and his company — they may possibly have reached the mines as they have had abundant time to do so; and yet I may not hear of or see them for a month to come, so extensive are the gold regions of California. Dr Ackley and Dr Graydon are mining somewhere on the South Fork and how they succeed is more than I can tell.

I have now given you the particulars of the mines, country, etc, as far as I can crowd them into this letter. I will write you monthly and keep you advised of all things here that I think will interest you.

I have, as yet, had no letter or paper from home. I feel a great anxiety to hear from you all, as I fear the cholera has visited our place and taken to the grave some dear friend. I will write to James and give him a history of my practice and my success in a short time, and you can see his letter. I have not heard from the States since the 30th of June. I saw the NY Tribune of that date and I found it full of interest.

Yours truly,

AW Harrison

The shady side of the Californaa Gold Rush

From the Vermont Phoenix (Brattleboro, Vt.) – February 09, 1849

The Bangor Whig and Courier publishes extracts of a letter from a gentleman at the Sandwich Islands, who had been at the mines in California for two months, furnished by Mr Dole of Brewer, Maine. After describing the cold region and the abundance of the precious metal taken daily, the writer continues:

“One might suppose from reading the above that digging gold is a very profitalile business, but there are other things to be considered. At San Francisco, board and lodging, three in a bed, or on the floor, is from $20 to $30 a week. Pork is $50 a barrel, and butter $1 a pound, at wholesale. At the mines, pork is $200 a barrel.

“And then the sickness. Nine-tenths of all who have gone to the mines have been taken sick. Hundreds were lying sick at Sutter’s Fort, unable to procure a passage to San Francisco, and suffering from want of attendance and of the necessaries of life.

“Bilious and intermittent fevers prevail to an alarming extent. Take all things into account, and I think those that stay at home the best off.

“Mr H has gone to San Francisco to see what he can do to persuade the people to lay up a treasure in Heaven. He will doubtless find full employment among the sick and dying. Two individuals who went from Honolulu base been murdered — one of them leaving a wife, a very excellent woman, and four or five children. He had been addicted to drinking and gambling.”