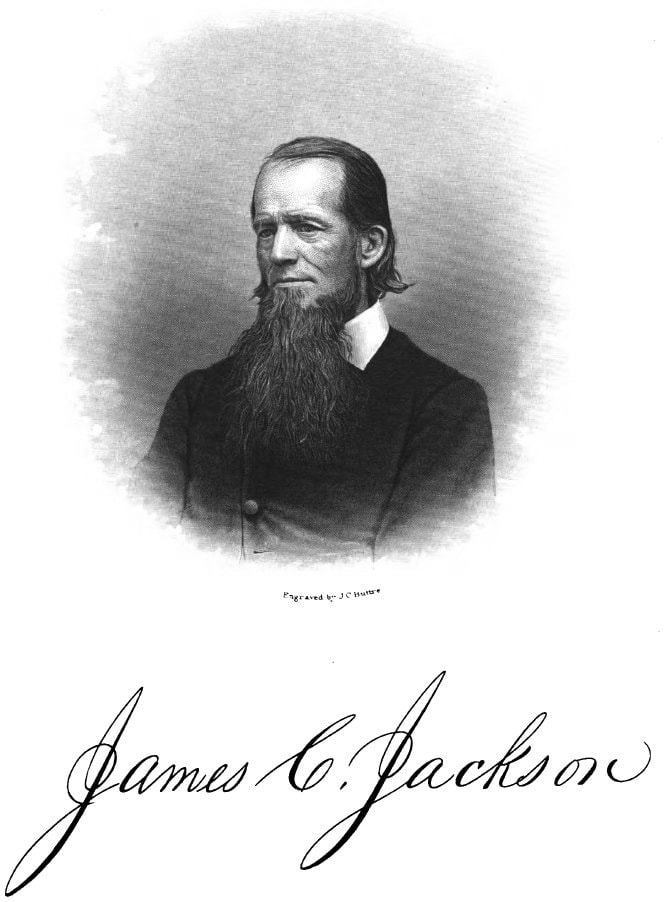

First published in 1861, The Sexual Organism, and Its Healthful Management by James Caleb Jackson MD dispensed what many people probably considered solid medical advice at the time.

In reality — and like much of the other health information written for the common people in the years leading up to the Civil War — the book offered far more opinion and supposition than fact. The author’s sentiments were summed up quite well by one line in the introduction: “The simple, unvarnished truth is, that human beings are born depraved.”

Among other topics broached within the tome’s 279 pages is the suggestion that you can spot a girl who masturbates because “such persons are apt to be flat-breasted… the breasts not filling as they could do under better and healthier states of the nutritive and secretory systems.” (You can tell the boys who commit the same dastardly deed by the way they walk.)

This particular vice, he says, “is a great, I think I might say the great, cause of their failure to achieve distinction in educational acquisitions, and high position in the departments of active life…”

Despite the many highly questionable statements in this book, Dr James C Jackson wasn’t a complete lunatic. He is known as one of the early promoters of a diet that emphasized fruits, vegetables and unprocessed grains; and is credited with having invented granola (which was originally named Granula).

As you might suspect, though, the man’s views on marriage and sex bears little resemblance to a modern-day “crunchy granola” perspective, as you can see below in an excerpt from Chapter V of The Sexual Organism and Its Healthful Management, in which the good doctor discusses “Marriage; Sexual Intercourse; Pregnancy; Abortion; Child-Bearing.”

On marriage & sexual intercourse, by James C Jackson MD (1861)

To parties who enter into marriage, the question may be properly raised, at what times and under what circumstances cohabitation should follow?

Of this I have to say, that most manifestly the law of sexual intercourse has a twofold bearing: that of propagation, and that of allowing a freer and more decided interchange of social feeling to take place, thus adding to the happiness of each and of both; and under these respective views should the intercourse proceed, either to what may be called a full or partial consummation.

Now, when it is to be had complete on the part of the male and the female, the law obtains, absolutely, that it should only be had at such periods or times as may be followed by the female becoming pregnant: Nature never intending that a man should lose his semen for any other purpose than that of propagating his species; or that woman should ever exercise her sexual faculty so as to reach her highest paroxysm of feeling, unless with a view to conception.

Artificial considerations come in, I am aware, to modify and qualify this statement: and I do not mean to be understood as affirming, that, where this rule does not obtain, great injury to health always ensues; but that this is the law, and that, abstractly considered, it is better to obey it than to violate it.

I know that writers of decided ability combat this view, declaring that, while the rule obtains in regard to lower animals, it does not obtain in regard to man; and the distinction which is clear in their minds is to be drawn just at the point of separation between the lower animals and man, as indicated by his possessing an order of faculties higher than theirs.

To them there is no liberty given, they argue, because they do not possess reason, and therefore must be governed by instinct, which is always exact and precise; but to man, who is clothed in addition to instinct with reason, liberty of action has been given.

In other words, that man is organized in this, as in every other direction, with discretionary power; and that this law cannot be said with propriety to operate with the same strictness of construction, with regard to him, as in the case of living organisms which are below him.

But I apprehend, that the fallacy of this reasoning is to be found in the extent to which it is carried. The reasoning faculties in man bear so close a natural relation to his moral sentiments, as that they are to be considered as constituting one, or nearly the same, group of organs or forces; and therefore are not to be separated.

Now, man, as a human being of the male gender, in his individual and moral nature, cannot by any means receive the highest culture without daily association and intercourse with a human being of the opposite sex; and woman, as a human being of the female gender, is subjected to the same great necessity. This is true of both, from a period as early as the dawning of responsibility to the close of life.

This view I have elaborated in a variety of ways in previous chapters, and endeavored to show that the sexes, in order to their highest individual development, should associate and be educated together; and that at adult age, other things not being in the way, marriage comes in as a consummation, and is therefore to be regarded as a sacrament as well as a civil transaction: carrying with it great force, imposing great duties; and, when properly lived out, affording the means of very great progression and happiness.

But, because these two parties are thus necessitated to live together by an organic arrangement which is vital, it does not follow that they are to violate that law of their natures which has reference particularly, and I may say exclusively, to the propagation of the species; or, in other words, to the reproduction of themselves.

Intercourse can be had, and, if people were properly educated and trained, would be had, short of all this. The man and his wife can be brought into sexual embrace without reaching the point of orgasmic action, and, in truth, inside of a full coition — where the relation may be said to be cohabitation simply; and where the means of pleasurable enjoyment, as well as of such interchange of thought, sentiment, feeling, and impression, can be made much more permanent, and productive of much higher good, than possibly can result from the exercise of the act to its fullest extent.

I urge this view because I am satisfied, from a thorough study of the organic relations of the sexes, that the faculty of amativeness has a twofold purpose, and should be always gratified by either sex from this point.

Where, then, the aim and intent are to have children, coition under sexual intercourse must take place. But, where only the gratification of the parties to be had, cohabitation simply, and not coition, should take place.

The physical and moral results under this view are found to sustain it. Where coition takes place, the parties feel, subsequent to it, a decided lassitude. Evidently, the nervous system has been so taxed as to subject them to extraordinary expenditure of force; and this can only be justified under the necessities of the case: that is, it can only be justified when the parties intend to have children.

So to relate themselves to each other as to be subject to this taxation twice a week, or once a week even, is surely to induce impairment of general vigor, and almost surely, at no distant day, to induce particular disease in some direction.

Physicians know full well that a class of diseases arises from undue sexual gratification, such as congestion of the brain; pulmonary diseases; dyspepsia; liver complaint; irritation of the kidneys; irritation of the bladder; irritation of the urethra; stricture; impairment of the nutritive organs; wasting away of the flesh; premature decay, indicated by mothy conditions of the skin; corrugations and wrinkles on the face ; exhibitions of posture, indicating debility.

These, and many others, are the direct result of great taxation of the nervous system, by and through the inordinate exercise of the sexual function.

Now, there is no justification for this in reason, certainly; nor is there in the moral sentiments: while, on the other hand, both protest against such use of this faculty as is legitimately productive of such results. And yet this is the only view that married people understand. They do not seem to know, or, if they do know, they do not educate themselves to act from any other view than this.

Men do not know how to cohabit without they exercise the coitive function; and women do not know how to be cohabited with, unless they submit to the fullest completion of the sexual processes. And, for want of this knowledge, great evils flow out of the marriage relation — so great, as in reality to be the cause of great unhappiness between the parties.

I know that I but speak the truth when I declare, that, of married women, a large proportion live on terms of mere sufferance with their husbands: for the most part feeling toward them no high instinctive longings, but, contrariwise, feeling disgusted rather; and are very glad when, from any cause or circumstance, a temporary separation from their bed and their embraces is compelled.

And so, too, do men, when disassociated from their wives, often feel themselves wondering that while, notwithstanding they cherish toward them only the most decided conjugal fidelity, they have no particular desire to enter into any close or intimate exhibitions of husbandly love, outside of the spasmodic manifestations in actual embrace.

Many are the husbands who, from week’s end to week’s end, show none of those exhibitions of attachment which they were so fond of bestowing during the period of courtship; and ignorantly and falsely attribute the lack of such feeling on their part to their discovery, subsequent to marriage, that their wives were lacking in the graces of character which they supposed them at that time to possess; when nothing is the cause of all this disrelish — I will not call it dislike — but a too frequent coition.

No man can keep up in his own consciousness a desire for close and intimate high association with a woman, who plays the part toward her of husband chiefly or entirely from the animal point of view. He must, in all his relations to her, seek to stop short of this; and instead of depression will come exaltation; and instead of his loving her less after sexual embrace, will he love her all the more.

For there is such a difference in the moral sentiment or emotion of husband and wife, when sexual intercourse has been merely cohabitative, from what it must be when coition has been performed, as. to make the distinction perfectly clear between the desire to remain in each other’s presence, and the positive desire of getting away from each other.

I do not believe that there is one case in a thousand where men and women so cohabit as to have coition, that they do not instinctively retire, feeling towards each other a state of indifference, and sometimes of disgust; whereas, were they to relate themselves to each other from points of strong spiritual assimilation, they would retire from such embrace with gentler and finer feeling than when they entered upon it: passing through, as it were, a group of desires, which relate the sexes to each other as animals, to a level of desire where the higher faculties come into play, and thus finding themselves by the process actually cultured and trained to a better order of growth and moral feeling.

Besides, the law of sexual intercourse, which has reference to the propagation of the species purely, and which therefore culminates in coition, cannot be violated without moral deterioration. This is to be seen in a great variety of manifestations, and might be enlarged upon extensively.

I shall leave it to the reader’s own good sense to carry out minutely the point already suggested: which is, that whenever such intercourse is had, from considerations that do not have reference to the propagation of the species, more likely than not the indifference or disgust which arises as a moral sentiment is to be found in close and intimate connection with the physical lassitude consequent upon such act.

Take the view from this plane; and, carrying it into its radiations, see what must be the effect ultimately on the relations and happiness of the married pair who live thus fourteen, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, or forty years.

Instead of growing toward each other, they inevitably grow away from each other. Instead of becoming like, they become unlike; and instead of finding that marriage, though it has been productive of offspring, has been to them a source of comfort and of increased enjoyment, they find it to have been not only a tax upon their freedom, but also upon their moral virtue.

The exercise of forbearance, and of all those qualities which teach us to be patient under afflictions, has steady and large drafts made upon it; and they live together rather by endurance than by mutual sympathy and affection.

If, therefore, married people will consent to be taught; and, being taught, will practice what they learn in this direction, they may have all the pleasure arising from the use of their sexual forces, without the thousands of discomforts and the positive diseases which now rise up to curse them; while, at the same time, they may have an almost unlimited freedom of exhibition.