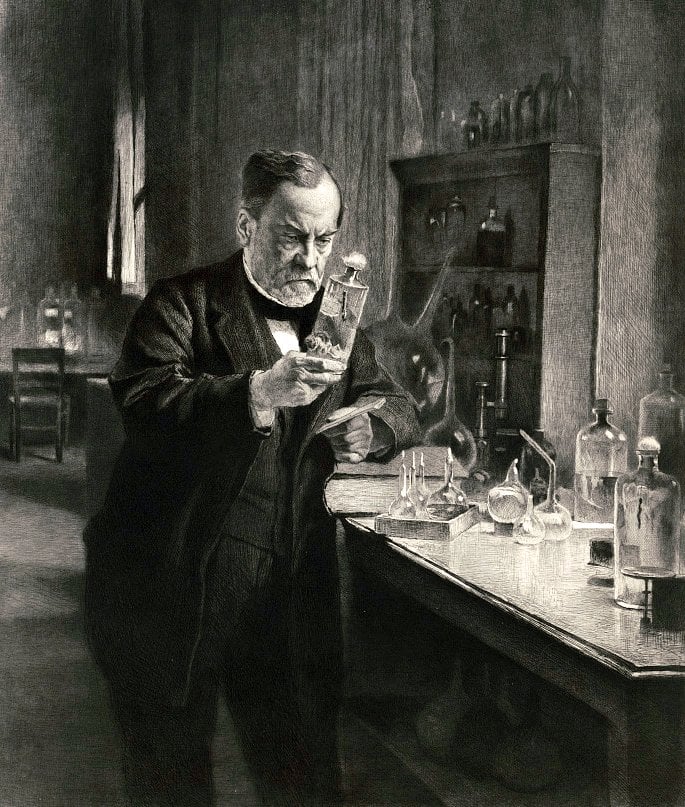

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist who created the first vaccines for both rabies and anthrax. Pasteur also invented the process that helps make milk and other liquids (and occasionally foods) safer to consume. That method is, of course, called pasteurization — and that word that is stamped on nearly every container of milk you can buy today.

Louis Pasteur, the first rabies vaccine, and preventive medicine (1961)

By Walter S Farquhar – Pottsville Republican (Pottsville, Pennsylvania) March 3, 1961

Louis Pasteur founded the science of immunization. He did it by disproving theories of his time.

He brought out a new theory of fermentation. Authority held it was incurred by contact of chemical elements. Pasteur said it was caused by living organisms, visible only under the microscope, which had to be introduced from without. He proved that dust was full of germs.

He plated a nutrient culture in flasks, then drew air into the flasks — and the germs grew and multiplied. Then, he took the flasks high into the Alps, where there was pure air, drew it into the containers — and no germs grew.

Pasteur experimented on fowls. He found that, if a culture was allowed to stand for an appreciable time, it lost virulence in proportion to the time, but that fresh germs inoculated into the chickens killed them.

That showed him that a culture could be attenuated into mildness. So he inoculated the birds with the mild culture, then with the powerful, virulent new cultures — and all the chickens recovered. Having resisted the mild attack, they had become immune to the deadly one. On that idea, now general, he was opposed as a charlatan.

And he won a great victory, on his theory, against the germ of anthrax in sheep. He inoculated a number of them twice with germs developed from a mild culture. Then he gave them deadly germs, fresh and powerful. And he inoculated an equal number of animals with the deadly germs, without first having given them the mild or attenuated ones.

All which had been given the prior mild germs recovered; all which had been inoculated only by the fresh germs died. The mild inoculation had created body resistance which fought off the deadlier germs. It had immunized them against anthrax.

Then he turned his attention to hydrophobia, or rabies. He inoculated dogs with the virus from mad ones — and noticed there was a variance of between 15 days and eight months before the symptoms showed. That gave him the idea that inoculation could cure hydrophobia if administered even after the biting, in the interval between the bite and the appearance of symptoms, provided it wasn’t too long.

So, he inoculated a dog which has been bitten by a mad one — and the “patient” recovered. Success, not only in immunization, but in curing rabies after a victim had been bitten, encouraged Pasteur to try his method on a human being.

And he got his chance in 1885, when the desperate case of a bitten boy was brought to him. The mother was frantic and willing to take any kind of a chance. But Pasteur, the true scientist, hesitated even then, before yielding to the mother’s piteous appeals.

When he finally consented, he gave the boy a series of 14 mild inoculations, gradually from old to newer. And the boy lived.

Pasteur, then, was swamped by victims of terrible hydrophobia. He treated some 350 and all but one survived, the lone exception having waited 37 days. Later 19 Russians, who had been bitten by a wolf — much worse than a dog — came to him. He saved 16 of them.

It could be said that Pasteur only emulated the idea of Edward Jenner, the conqueror of smallpox. But the amiable English physician acted only in an empirical way — from the experience of persons who knew that anybody who had been affected by cowpox, a mild form of smallpox, never became afflicted by the latter deadly disease. Dr. Jenner did not have the knowledge of bacteriology which came later. Pasteur, then, was the father of preventive medicine.

Through it all, Pasteur had the loyal support of Dr. Joseph Lister, who did have knowledge of germs, and who was impressed by Pasteur’s discovery of the true cause of fermentation.

Pasteur, a chemist, did not find the germ of hydrophobia. He left that to the medical men. But one of his disciples, Negri, discovered it in 1903… And, before Pasteur died, another of his disciples, Emilie Roux, developed the diphtheria antitoxin, in 1894. And, in the same year, still another, Alexandre Yetsin, found what men had been striving to study for centuries: the bacillus of bubonic plague, concurrently with the Japanese doctor, Saibasabuco Nitasato. For that, both deserve undying fame. It was Pasteur who had inspired them.

Louis Pasteur was one of humanity’s all-time benefactors. And he did his great work against the jealousies which noble accomplishment always arouses. His last words were: “Much has been done, but there remains a great deal to do.”

Original news report of the first rabies vaccine, from 1885

Daily Evening Bulletin. (Maysville, Kentucky) October 31, 1885

No more hydrophobia: Dr Louis Pasteur’s cure for the mad dog’s bite

No more hydrophobia! No more mad dogs! Dr Louis Pasteur’s experiments have resulted in a most brilliant success at perhaps the most important sitting held by the academy of sciences.

Dr Pasteur thus described the process of cure by means of a rabbit inoculated with the fragment of tissue taken from the spine of a rabid dog. The incubation of the poison occupied fifteen days.

As soon as the first rabbit inoculated was dead, a portion from its spinal marrow was in turn inoculated into a second rabbit, and so on, until sixty rabbits had been inoculated. At each successive inoculation, the virus increased in potency, and the last period of inoculation did not occupy more than seven days.

The scientific process

Having ascertained that exposure to dried air diminished the virus, and consequently reduced its force, Dr Pasteur supplied himself with a series of bottles of dried air. In these bottles, he placed portions of inoculated spinal marrow at successive dates, the oldest being the least virulent and the latent the most so.

For an operation, Dr Pasteur begins by inoculating his subject with the oldest tissue, and finishes by the injection of a piece of tissue whose bottling dates back only two days, and whose period of incubation would not exceed one week. The subject is then found to be absolutely proof against the disease.

A boy, twelve years of ago, named Meister, who had been bitten fourteen times, came from Alsace with his mother to see Dr Pasteur. The autopsy of the dog which had bitten the boy left no doubt as to it having suffered from hydrophobia [rabies].

Dr Pasteur took the celebrated Dr Vulpian and a professor of the school of medicine to see the boy Meister. These two doctors came to the conclusion that the boy was doomed to a painful death and might be experimented upon.

In thirteen days, inoculations were made upon Meister with pieces of spinal marrow containing virused of constantly increasing strength, the last being from the spine of a rabbit that died only the day before.

Now a hundred days have passed since Meister underwent the last inoculation. The treatment has been thoroughly successful and the boy is in perfect health. He had been bitten sixty hours and had traveled from Alsace to Paris before the first inoculation was performed.

A shepherd boy named Judith, aged 15, was bitten by a mad dog a fortnight ago, and has now been a week under treatment. Dr Pasteur is confident of curing him.

Having inoculations at the ready

Dr Pasteur said that it was now necessary to provide an establishment where rabbits might always be kept inoculated with the disease. In this way, a constant supply of spinal tissues of old and recent inoculation would always be ready.

Before the sitting was adjourned, Dr Pasteur received an enthusiastic ovation from both the academy itself and the public who were present. Among those present was noticed the Grand Duke Alexis, who is a great dog fancier, and M de Lesseps, who went to hear Dr Pasteur’s report endorsed by Dr Vulpian.

One of the leading doctors present remarked that the question was whether a man cured of hydrophobia could suffer from a second bite. In other words, whether the inoculation of virus was a guarantee against hydrophobia.

In answer, Dr Pasteur stated that the malady is transmissible only by bite. If, therefore, by a general compulsory inoculation of dogs for several generations — dogs had been made incapable of hydrophobia — the malady would have disappeared, and there would be no occasion to ask whether inoculation had a permanent effect or not.

Where did rabies come from?

As to the origin of hydrophobia, Dr Pasteur says nobody in the world can explain its primal causes. As he remarked — perhaps out of politeness — his theory will require study by the profession in order to make it practical, but he emphatically stated that the cure for hydrophobia had been found.