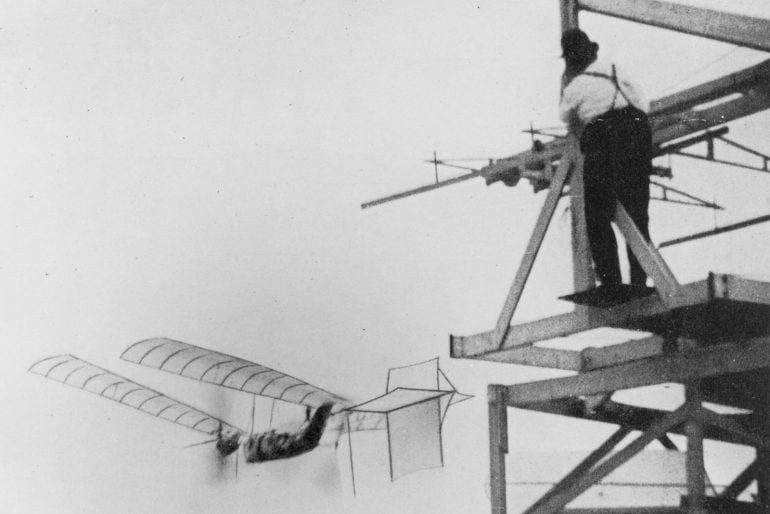

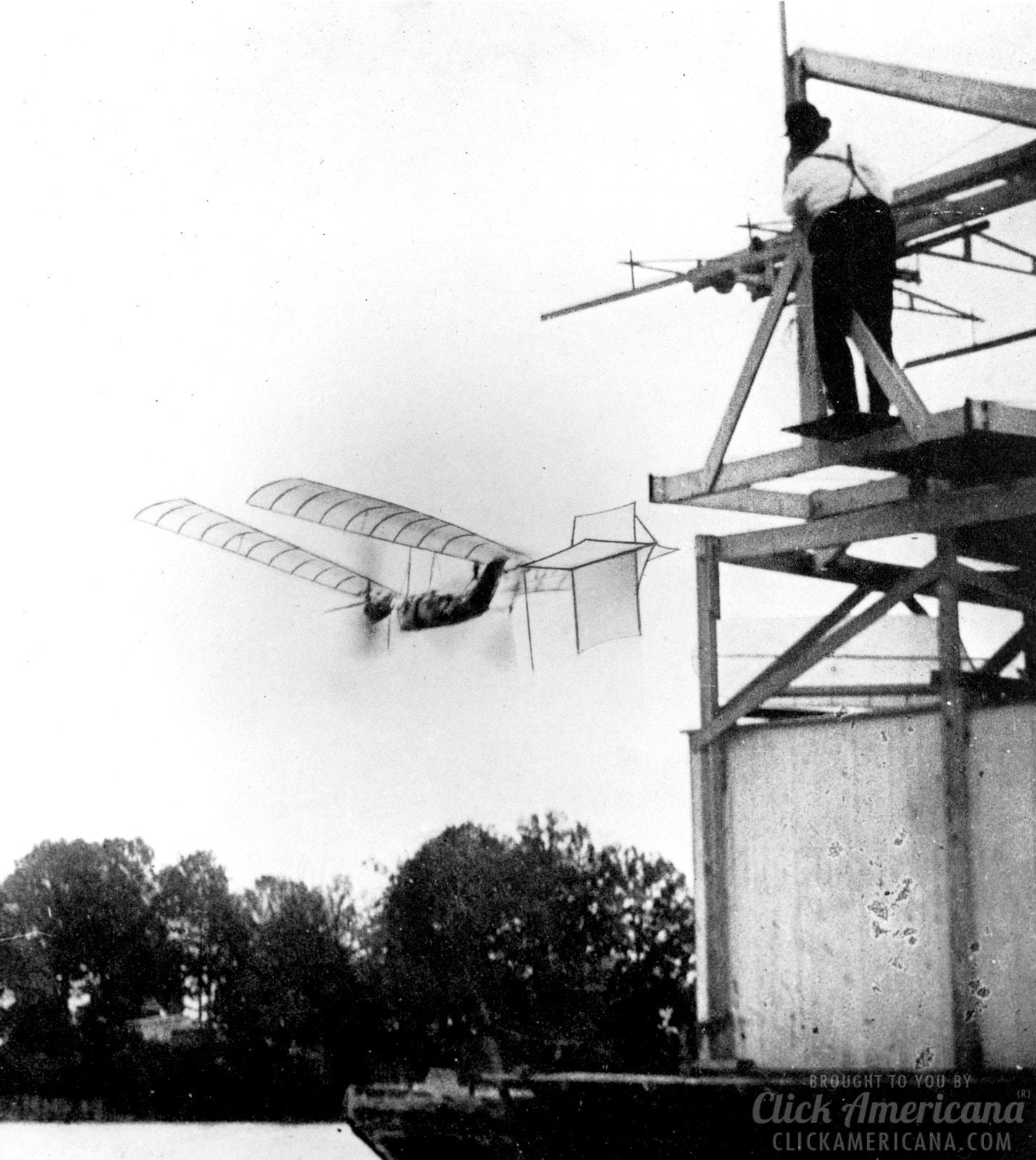

Alexander Graham Bell, who had already made his name with the telephone, was invited to see one of Langley’s demonstrations on the Potomac River. What he witnessed surprised him — not just because the machine worked, but because of how smoothly it flew. Langley’s model, called Aerodrome No. 5, looked something like a metal bird. It lifted off, circled in wide spirals, and climbed to about 100 feet before gliding down and settling on the water without a crash or a wobble.

Video: Simulation of the flight of Aerodrome No. 5 on May 6, 1896, created by Digital History Studios and the Langley Flight Foundation

Bell said the flight was so significant that the public ought to know about it. The Aerodrome weighed just 25 pounds, ran on a one-horsepower steam engine, and used two propellers to maintain lift. It wasn’t built to carry a person, but that wasn’t the point. Langley wanted to prove a machine could fly — and do it with stability and control. Once that problem was solved, he figured a larger engine and airframe could follow.

At the time, flying machines still felt like fantasy to most people. They were either seen as carnival stunts or impossible dreams. Langley’s methodical approach didn’t get the same attention as the Wright brothers’ later flight at Kitty Hawk, but his results were hard to ignore. He showed that controlled, powered flight wasn’t just an idea — it was already happening.

Below, we’ve collected Bell’s original statement and photos from that test run — including the launch of the Aerodrome on the Potomac. It’s one of those overlooked turning points in technology, when the future was already in motion, even if the rest of the world hadn’t caught up yet.

Flight is a fact

Professor Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, has witnessed the trial flights of the machine devised by Professor Samuel P Langley, formerly of Pittsburg. Mr Bell makes the following statement:

“I witnessed a very remarkable experiment with Professor Langley’s aerodrome on the Potomac River. Indeed it seemed to me that the experiment was of such historical importance that it should be made public.

“I should not feel at liberty to give an account of the details, but the main facts I have Professor Langley’s consent for giving you, and they are as follows:

“The aerodrome, or ‘flying-machine,’ in question was of steel driven by a steam engine. It resembled an enormous bird, soaring in the air with extreme regularity in large curves, sweeping steadily upward in a spiral path, the spirals with a diameter of perhaps 100 yards, until it reached a height of about 100 feet in the air, at the end of a course of about half a mile, when the steam gave out, the propellers which had moved it stopped, and then to my surprise, the whole, instead of tumbling down, settled as slowly and gracefully as it is possible for any bird to do, touching the water without any damage and was immediately picked out and was ready to be tried again.

Video: Why Build Aerodrome No. 5?

“The flying-machine carries a small steam engine of one horsepower. The whole contrivance weighs twenty-five pounds. Its light steel framework holds extended horizontally three sheets of thin canvas, one above the other. The length overall is fifteen feet. The engine runs two propellers.

“Professor Langley will soon construct a flier of large size, which will carry a proper mechanical equipment and be capable of extended flight. The one described is only a model for experimental purposes. The inventor has not troubled himself to any extent about the question of a suitable engine, which could be furnished easily enough when needed.

“The problem was to make a machine that would fly, and fly in the right way; this accomplished, there was no difficulty in supplying the power required for a lone trip.”

Top photo: Launching of Aerodrome number 5 on the Potomac River (May 6, 1896) Courtesy Smithsonian; Photo 2: Professor Samuel P Langley.