Daddy Warbucks and Little Orphan Annie to the rescue

Excerpted from Newsweek – May 2, 1977

All season, Broadway had gone without a major musical, and things were desperate. The dog days were coming, and so were the Tony awards, with their national TV exposure, and the Tonys without a musical would be like Howard Cosell with lockjaw.

And then last week, Daddy Warbucks and Little Orphan Annie came to the rescue.

What, you say, has the man gone mad? What have the protagonists of a half-century-old comic strip got to do with Broadway — especially those protagonists, the eternally pubescent tyke and the omnipotent plutocrat with the skull of Kojak and the political philosophy of Attila the Hun?

In a second coming more mind-boggling (and possibly more profitable) than that of King Kong, Harold Gray’s archetypes of the primal American dream have become the heroes of the season’s prayed-for big musical, ANNIE.

It’s hard to see how “Annie” can miss running until Andrea McArdle, the spunky, talented 13-year-old who plays the title role, outgrows waifdom.

“Annie” may well become the “Hello, Dolly!” of adolescence, with red-thatched Annies and depilated Daddys in companies all over the land and, finally, a black Annie, a Chicano Annie… in short, Little Orphan Annie is back, Broadway has got her, and she apparently is to be the mascot of the new age of hope, optimism and simplicity that’s coming in with President Carter.

Make no mistake about it, this “Annie” is an incredible achievement. In that mixture of luck, instinct and doggedness that is the mad genius of popular culture, director-lyricist Martin Charnin (who conceived the idea), writer Thomas Meehan, composer Charles Strouse and producer Mike Nichols have tapped a sensitive nerve in their audience like a bunch of wild-catters hitting a pool of oil.

“Annie” bids fair to be a theatrical gusher, drenching its creators in black gold and its audiences in tears of sentimental ecstasy as they flee from a confused reality to a warm fantasy of love and succor.

Kid reactionary

“Annie” wastes no time in setting up its broad, clear, magnificently cornball images.

The show opens in the New York Municipal Orphanage, Girls’ Annex, in mid-Depression 1933. It’s a Dickens-cute world in which Annie and her chorus of adorable fellow-waifs sing “It’s the Hard-Knock Life” as they scrub the floors at 4 am under the baleful eye of Miss Hannigan.

This character is played as a manic descendant of Cinderella’s stepmother by the outrageously hilarious Dorothy Loudon, who blows her whistle and swigs her hootch with equally forlorn passion and wails her anthem of child hatred, “Little Girls.”

Depression-chic

“Annie” is a fantasy of rescue. Sweet, gutsy little Annie has to be rescued, not only from Miss Hannigan, but from the real world, which has nothing a good little girl would want except the lovable scruffy mutt Sandy, whom she picks up during a momentary escape front the orphanage.

The ambiguous spirit of”Annie” is graphically embodied in the scene in a Hooverville where Annie takes refuge. Here the out-of-work and downtrodden sing a cartoonized Brecht-Weill number sardonically thanking Herbert Hoover for their fate. It’s like a tarted-up “Threepenny Opera” — the characters may be on the skids, but they’re dressed in Depression-chic clothes and their shantytown proudly flies an American flag.

Annie’s too nice to become a patriotic pauper, so we don’t worry when she’s hauled back to the orphanage. Sure enough, Daddy Warbucks, played as an amiable boob by Reid Shelton, takes her away, promising to find her real parents via radio’s “Hour of Smiles.”

We secretly hope he won’t succeed, because the parents are probably patriotic paupers and we want Annie to have Daddy’s billions and all those smiling servants, who seem to have the only good jobs in Depression America.

After all, Annie deserves it — it’s she who goes to Washington with Daddy and inspires that amiable boob of a President, FDR, and his bumbling Cabinet to come up with the New Deal when she jumps onto a table and sings hopefully about “Tomorrow.”

So it’s only justice when Daddy personally hires the FBI, which discovers that her parents are dead and unmasks the villainous Rooster (Robert Fitch), who’s posing as Annie’s real father. Annie has earned that moment when she comes down Daddy’s lavish staircase, gussied up at last in the cartoon’s famous frizzy hairdo and simple, virtuous red dress.

Corny but catchy

“Annie’s” startling achievement is to make a contemporary audience accept this shamelessly old-fashioned cartoon fantasy. It does this not with dazzling theatrical brilliance, but with a deceptive simplicity that masks a knowing intelligence and with a deliberate rejection of the musical theater’s recent hard-won sophistication.

Strouse’s music is in its way a tour de force — it’s not easy to write corny but catchy tunes like “The Hard-Knock Life,” or “Tomorrow.”

Sometimes it’s too tough even for Strouse — Daddy’s “Something Was Missing” is abjectly banal, although it may seem more so because of Charnin’s lyrics: “The world was my oyster, but where was the pearl?/Who dreamed I would find it in one little girl?”

Little Andrea McArdle is no showbiz brat, but a straight, gritty performer who sings appealingly, hitting her notes clean and phrasing like a mini-Merman. Raymond Thorne is amusing as FDR, his cigarette atilt, mouthing homilies at his unappreciative Cabinet.

But the show badly needs the maniacally baroque performance of Dorothy Loudon. Loudon raises mugging to a high art — she mugs with her face, her voice, her body — I swear she mugs with her very mind. Her dashingly funny performance tells the audience that it’s all really a gag.

But what makes “Annie” a cultural phenomenon is that the audience doesn’t ultimately take it as a gag.

The line that dissolves “Annie’s” viewers into jelly (at $17.50 a jell) has got to be the simplest line in the modern theater: “I love you, Annie,” says Daddy, his diamond stickpin glistening like a million-dollar tear.

An example of a vintage ‘Little Orphan Annie’ comic strip from 1934

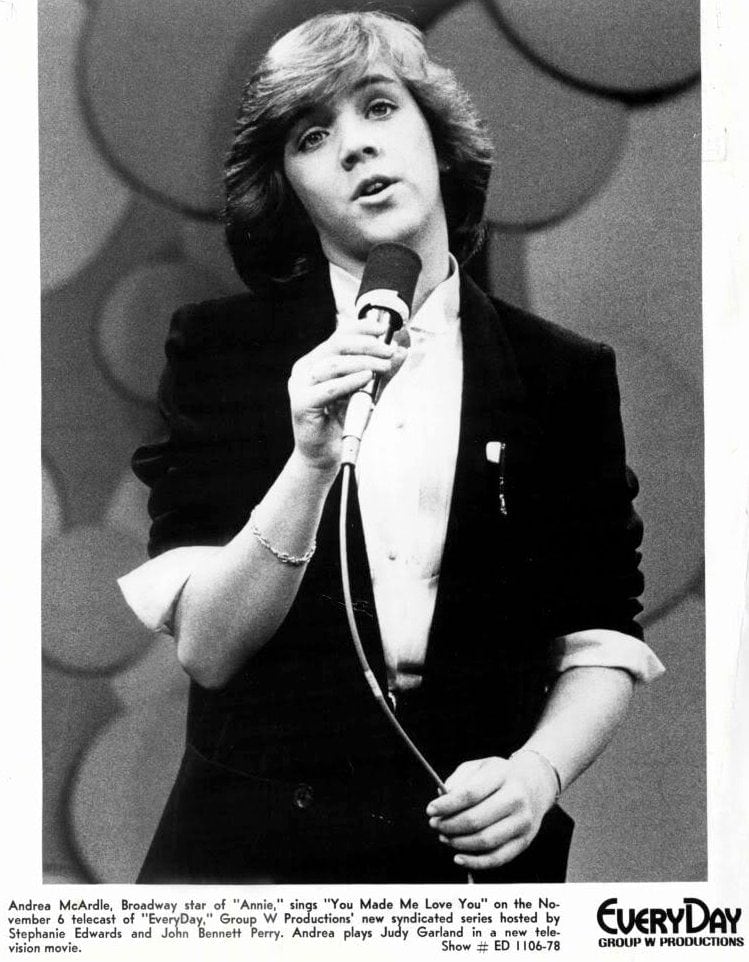

Andrea McArdle: Annie star & pinball player

From The Journal News (White Plains, New York) June 28, 1977

When 13-year-old Andrea McArdle isn’t singing and dancing the lead role in “Annie,” Broadway’s new musical hit, the tiny redhead is racking up points at a pinball parlor down the block.

“I honestly believe she wouldn’t show up for performances if she knew she could play pinball all day,” says her mother, Phyllis McArdle, who babysits amid the arcade’s psychedelic lights and deafening bells.

Although Andrea’s five-year career has included roles in TV commercials and on daytime soap operas, she soared to instant stardom with her performance as “Little Orphan Annie” of comic-page fame.

She and her trusty terrier, Sandy, soon will be advertising dog food, staring up from wristwatches and gracing T-shirt fronts as Madison Avenue tries to cash in on the nostalgia craze.

Her hometown of Philadelphia, where she began her pinball addiction, has asked her to march in its Fourth of July parade. The 56-1/2-inch, 77-pound performer admits she enjoys most of the attention, but not when it interferes with her $5-a-day worth of Star-Gazing, Pongplaying and other machine fun.

“I can’t get through a whole game without someone asking for an autograph or stopping me to say hello. It’s very nice, and all, but I wish they wouldn’t distract me,” she says. “Pinball looks easy, but it’s not.”

Andrea wasn’t always in the spotlight. In summer-stock in Connecticut, she played one of the little orphans until the director plucked her from the chorus and pushed her into the lead.

She had two days to learn the lines. “That was frightening,” her mother recalled. And before they knew it, the musical was on Broadway. “That wasn’t so exciting,” Andrea says.

Andrea, who wears a curly wig for part of the show, refuses to smear on stage makeup. Her short brunette tresses are dyed red by her mother, a former hairdresser, to match the Annie image.

“I’m never scared when I go on stage,” Andrea explained, straddling an easy chair in the West Side hotel room where her family has taken up temporary residence. “I like it best when I’m singing with the other orphans. They’re all my friends.”

Andrea performs in eight shows a week, including two matinees. Then she returns to Philadelphia to see her father, Paul, an Amtrak statistician, and say hello to her best friend, Lisa Hobson.

It’s a long day for a 13-year-old, with homework and tutoring squeezed around her pinball play — not to mention hours spent at publicity interviews. One night she even dined with Frank Sinatra.

Nor does she have time to answer the hundreds of letters she gets. Some of them, from love-sick adolescents, make her giggle. Others she describes as “weird, really weird,” like the letter that said she would be blackmailed if she didn’t enclose two “Annie” tickets.

“I like boys, but I have plenty of time for that when I grow up,” Andrea says. “Right now, I’m having too much fun.”

Annie star Andrea McArdle plays ball with the Bad News bears & Jackie Earle Haley