Buddy Holly songs continue to rock our world

His innovative musical techniques, iconic black-framed glasses, and a catalog of hit songs like “That’ll Be the Day” and “Peggy Sue” have cemented Holly’s place as a true legend. Though his life was tragically cut short, his influence reverberates through the music industry even today.

Join us as we explore various Buddy Holly songs, his incredible career, and uncover some fascinating anecdotes about this musical pioneer.

The career of Buddy Holly (1967)

By Norman Mark – The Los Angeles Times (California) September 3, 1967

At 1:50 a.m. on Feb. 3, 1959, a single-engine, four-seat Beechcroft Bonanza took off from a Mason City, Iowa, runway into light snow and 35 m.p.h. winds.

Fifteen minutes later, the left wing tip grazed a cornfield five miles north of Clear Lake, Iowa. The plane plowed up two city blocks of earth and came to rest against a fence. No one heard the crash.

The occupants were the pilot and three rock ‘n’ roll stars, J. P. (Big Bopper) Richardson, known for his record “Chantilly Lace”; Ritchie Valens, who sang “Donna,” and Buddy Holly, 23, who had recorded “It Doesn’t Matter Any More” just two weeks earlier. All were dead.

Well you left me here

So I could sit and cry

Well, golly gee, what have you done to me?

Oh, well, I guess it doesn’t matter any more.”

Before the accident that ended his career, Buddy Holly had received two gold records for selling more than 1 million copies each of the songs “Peggy Sue” and “That’ll Be the Day.” Before the accident, he had sold about 5 million records. Many more have been bought since.

Buddy Holly was young, eager and married only six months when he died. Killed at the height of his popularity, he has become the center of a cult that has quietly grown around his memory.

Every time one of his records is reissued, or a tune of his is discovered on a forgotten tape, the cult grows. His sales have continued at about the level of old Glenn Miller albums.

Many record stores keep two, three or four different albums in stock, re-ordering when needed. He sells well in Chicago, better in Wisconsin, and best of all in England.

An early skepticism

A legend, approaching that of a folk hero, is growing about him. Some say that his West Texas “rockabilily” sound of the 50s became the British sound of the 60s. That the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and many others owe a good part of their styles to him.

That the very name, “The Beatles,” copied a Holly-started insect trend, for his group was known as the Crickets.

That the Crickets were one of the first groups to accompany themselves on drums and guitar.

That Buddy Holly would have been one of the greats if his career just had been a little longer than 30 months.

MORE: The day the music died: Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens & Big Bopper killed in plane crash (1959)

Fact, fiction and fable have blended over the years and it is difficult today to learn how it all happened. But his mother and father still live in his home town of Lubbock, Texas; the recording studio that gave him his big break is still in Clovis, NM, and the New York executives he dealt with are still in Manhattan.

Young Buddy Holly: The star’s early life story

Charles Harden (Buddy) Holly was born Sept. 7, 1936. His father, Lawrence 0., now 65 and a retired tile contractor and Jack-of-all-trades, remembers Buddy imitating radio commercials on a dime store bugle at 5, but admits that the bugle-playing soon stopped around the Holley house.

At 12, Buddy began taking piano lessons, but as he often said later, “I got sick of both and took up the guitar. That was what started it all.”

His two older brothers, Larry and Travis, now owners of the Lubbock Ceramic Tile Co., both played guitar, and perhaps it was the tag-along kid brother in him that gave Buddy his desire to play.

Buddy and Bob Montgomery, a fellow Lubbock high school classmate who is now head of United Artists Records in Nashville, had endless singing and writing sessions. Soon they entertained on school buses and in assemblies.

When they were juniors, “Flower of My Heart,” by Bob Montgomery, was chosen for inclusion in the 1954 school yearbook.

ALSO SEE: How Bill Haley & His Comets rocked around the clock when rock ‘n’ roll was brand new

In September 1953, a man named Dave Stone was opening KDAV of Lubbock, “The Original All-Country and Western Music Station.”

Before the station went on the air, the boys were begging for a chance before a microphone. Stone gave them the 2:30 p.m. spot on the Sunday Party Show.

For a half-hour each week for almost three years, the boys sang their own songs and listeners’ requests. For this, they were paid nothing, but they didn’t have much of an audience then, either. But in the spring of 1954, Elvis Presley visited Lubbock.

It was the sort of thing that makes for legends — Buddy and Elvis meeting before both became famous. (Elvis did not record “Heartbreak Hotel” until 1956.)

There is even a story that Col. Tom Parker, Presley’s manager, tried to help Buddy’s career, but just what he did, or if he really did it, is lost in the past.

“The boys talked with Elvis for a long time,” Stone recalls. “They decided to change their style. The next week I was announcing the show and my wife was answering the phones, when, without our knowing about it, the boys started their new sound. Where there had been little interest before, suddenly the phone rang off the wall.

“It wasn’t exactly Presley’s style, it was something in their own vein,” Stone said. What it was was “rockabilly,” a combination of rock ‘n’ roll and country and western.

Holly would sing something like “Blue Suede Shoes,” but with his own imprint. The style change worked, and soon The Buddy and Bob Show was heard on KDAV.

By fall, Stone, who now owns four radio stations, was booking the boys in Lubbock’s Fall Park Coliseum with Bill Haley and the Comets. (Thus completing the chance meetings of a triumvirate that would soon have a great deal of influence in pop music: Presley, Haley and Holly.)

Shortly after Holly met the Comets, a Decca Records executive called from Nashville and asked to see Buddy.

Holly was quickly given a one-year contract; he recorded a few demonstrations, and was just as quickly released when an executive said that Holly was the least talented of any artist with whom he had ever worked.

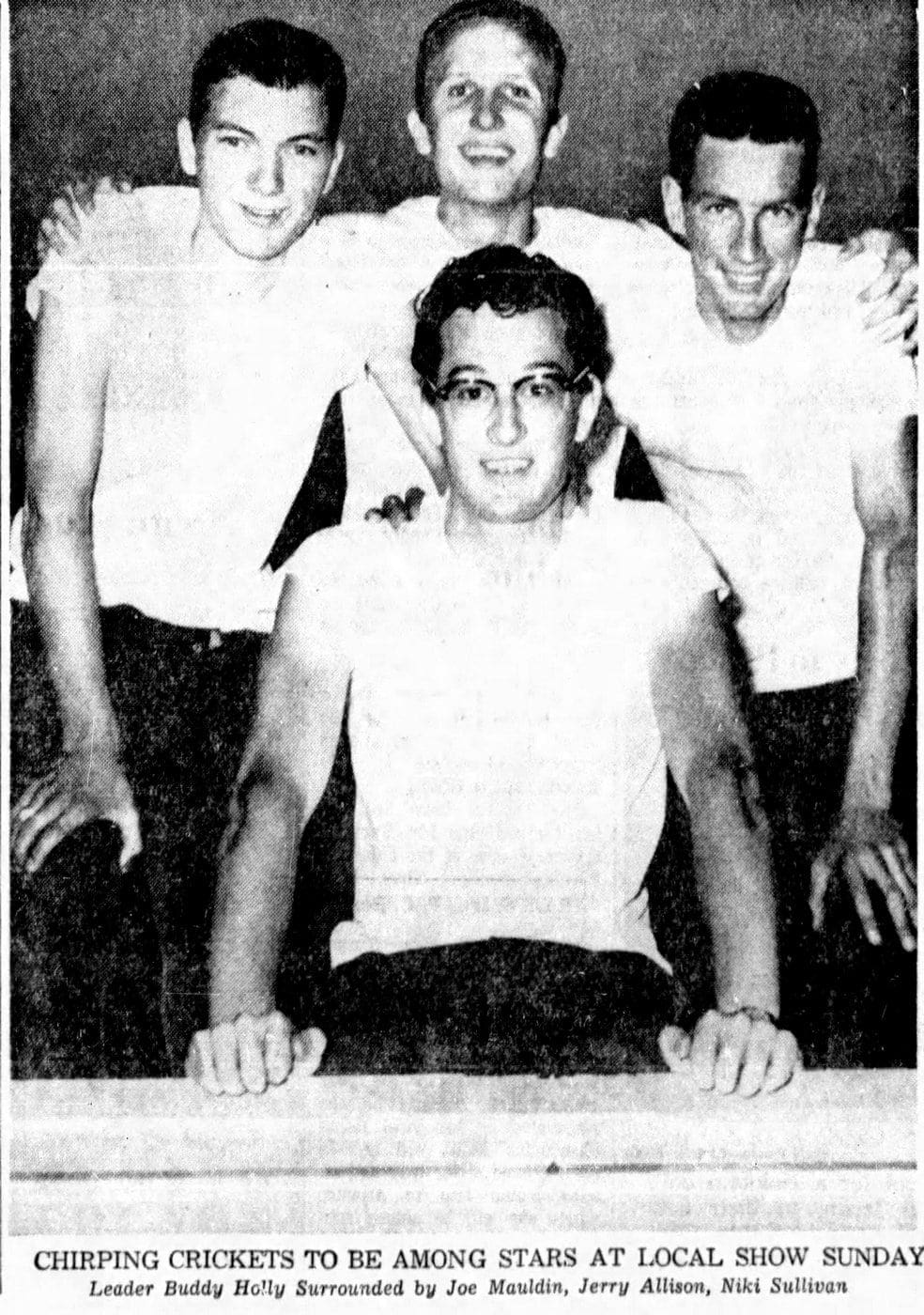

His interest in music continued and, with some high school friends, he formed the Crickets. (One of them, drummer Jerry Allison, is now with Roger Miller in Las Vegas.)

The tales say that Buddy and the Crickets piled into Buddy’s old jalopy and drove to Norman Petty’s recording studios in far away Clovis, New Mexico, where they were immediately discovered.

Actually, Buddy borrowed his fathers’ used-but-working car, drove a short 100 miles to Clovis, where he met Petty, and worked hard for success.

The Crickets’ first release, “Words of Love,” was “covered” (also recorded) by a group called the Diamonds, and Buddy’s first record was a hit for someone else.

The boys then recorded “That’ll Be the Day,” by J. Allison, N. Petty and B. Holly.

“That’ll be the day

When you make me cry-ay-ay,

You say you’re gonna leave

You know it’s a lie

‘Cause that’ll be the day-ay-ay

When I die.”

The song was sent to Brunswick Records, a subsidiary of Decca, which had just fired Buddy.

The Crickets signed a contract with Brunswick. For three months, the record had no sales. Then, so the story goes, in June 1957, a Buffalo, N.Y., disc jockey locked himself in the control room, and played “That’ll Be the Day” on the air all day long.

Buddy Holly songs: Performing “That’ll Be the Day” with The Crickets on The Ed Sullivan Show

MORE: Rock ‘n’ roll music: The new teenage dance craze (1955)

Buddy Holly was on his way. From June 1957 until February 1959, Buddy Holly was one of the biggest. He appeared on nearly every television variety program (twice on Ed Sullivan), issued albums and more singles. He began recording without the Crickets.

Dick Jacobs, who did many of Holly’s later arrangements, remembers, “I first met him when he was appearing in Brooklyn. He had silver-rimmed glasses, gold-rimmed teeth, and looked like a hick from Texas.

“The next time I saw him, he wore a three-button suit, horn-rimmed glasses, had had his teeth recapped, and looked like a gentleman. He was always a marvelous person . . . a sweet, gentle soul.”

Why 1958 was Buddy Holly’s biggest year ever

His big year was 1958. There was an 80-day tour of America, a two-week visit to Australia, and four weeks in England performing with the Everly Brothers.

It was also in 1958 that he met and married Maria Elena Santiago, a receptionist at Southern Music Publishing Co. (Since the accident, she has remarried and lives in Mt. Vernon, N.Y., with the three children from her second marriage.)

With his last recording sessions, early in 1959, Buddy Holly was again changing styles. Once deeply immersed in the country and western idiom, he was now a rock ‘n’ roll star. At Petty’s suggestion, however, he tried ballads, surprising everyone with the sales of “True Love Ways.”

Buddy Holly songs: True Love Ways recording

Jacobs remembers, “His last recording date was for 7 p.m. About 5 p.m., he came running into my office excited about just seeing Paul Anka.

“Anka had given him a song and would I mind writing the arrangement to it? Buddy kept on humming and singing the song while I wrote the notes. We had to use a pizzicato string effect because we didn’t have time for anything else.

“The song, ‘It Doesn’t Matter Any More,’ recorded two hours later, became a hit, and the strings became a big thing in England.”

Petty recalls a similar, seemingly accidental, incident. “Once, in the studio, he did this little hiccupping thing, kind of like hiccupping through the word. I think he did it to make me laugh in the control room. We left it on the record and soon everyone was imitating it.”

Buddy Holly songs: Recording of “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” written by Paul Anna

Two weeks after recording “It Doesn’t Matter Any More,” the plane took off from Mason City.

“When he died, there was a numbness,” his mother said. “Each year we thought, well, this is the end of it, but each year it has gone on.”

Standing “just a half-inch from six foot,” according to his father, weighing about 150 pounds, Buddy Holly’s thinness and his glasses gave him a shy off-stage appearance.

When told he couldn’t be a hit and wear glasses, he said, “You wouldn’t want me to fall off the stage, would you?”

From all reports, any timidity disappeared on stage and Holly became a dynamic performer. After Holly’s death, the record company tried to find every Buddy Holly record and tape that it could.

Buddy often worked with a home tape recorder, singing to it and then having an arranger take down the exact notes when Buddy was in New York or New Mexico.

Nearly all of these home tapes have been re-recorded, with vocal and instrumental backing added, and released for the fans.

Holly fans still going strong

Buddy Holly now has 10 albums (including one released this March) containing about 85 songs, of which 30 were written either by himself or in collaboration with someone else.

One album, “The Buddy Holly Story Part 1,” issued after his death, was on the top 100 charts for 3-1/2 years and sold 2 million copies. And there are about a half dozen Buddy Holly records yet to be released.

Buddy Holly songs: Performing “Oh Boy” with The Crickets on the Ed Sullivan Show

With Buddy Holly memorial and appreciation societies in West Germany, France, Holland, England and Crown Point, Indiana, the fan mail still comes to Lubbock. Each time another group records one of his songs, interest renews.

The Beatles have used “Words of Love” on two albums; the Rolling Stones’ first hit was “Not Fade Away,” which they have recorded four times, and Herman’s Hermits have sung “Heartbeat” — all since 1956.

In his life, Buddy Holly reflected every major strain of popular music of his time. Often appearing in rhythm and blues shows, he had a strong country and western background that was influenced by rock ‘n’ roll.

His voice, a bit high, a little nasal with a Texas twang, was getting deeper and was losing its accent near the end of his career, when he began recording ballads.

There was talk of an album of show tunes, many more television appearances and some nightclub work.

“There’s no use in me a-cryin’

I’ve done everything and I’m sick of tryin’

I’ve thrown away my nights

And wasted my days

Over you …”

Buddy Holly: The ‘Holly Era’ survived long after the originator died (1975)

Lubbock Avalanche-Journal (Texas) February 2, 1975

AMONG PEOPLE who keep up with the beats and moods of popular music, Buddy Holly’s name is one which will never be forgotten.

In fact, the period of 1957-59 is known as the Buddy Holly Era. It was the summer of 1957 which marked another milestone in the maturation of Rock ‘N’ Roll.

Out of Lubbock came the sound of Buddy Holly and the Crickets. They first leaped into national prominence with “That’ll Be The Day,” a happy-go-lucky, twangy melodic song that immediately soared near the two-million mark in sales.

The big, thumping back-beat introduced by the Crickets — a group of four high school chums of Holly’s — was flattered by instant imitation; it became assimilated into the structure of modern rock and played an important role in nearly all records released up through 1966.

The voice of Buddy Holly was a little more difficult to imitate, but a lot of people tried — resulting in varying degrees of success.

“FROM A musical standpoint, Buddy was one of those rare virtuosos that shapes the destiny of a musical era,” wrote Maury Dean in a book entitled “The Rock Revolution.” In the book, Dean outlined the type of music which developed in the early 1950s, and continued until the 1970s.

“Buddy’s voice was a combination of precision and control; it was the outward sign of his exuberant personality,” Dean said. “He went so far as to invent a vocal trademark (its linguistic relative is defined as a glottal stop) that defies normal explanation and must be heard to be believed.

MORE: See 20 vintage jukeboxes, including Classic Rock-Ola & Wurlitzer machines

“Buddy’s first-rate vocal mastery and sparkling personality instantaneously pushed the sound of Buddy Holly and the Crickets to the top of the record charts,” he said.

The thundering beat of Holly and his Crickets symbolized the era. Their songs were heard all over the world; “Oh, Boy,” “Think It Over,” and “Maybe Baby” easily earned gold records from the combined merits of their danceable beat and catchy lyrics — but mostly from Buddy Holly’s voice and a newly found sound.

BUDDY’S BIGGEST record, “Peggy Sue,” was cut as a single artist. It used three unique innovations and sold three million records almost instantly.

One innovation was an accented, sixteenth-note drum roll throughout the song. Jerry Allison, Buddy’s drummer, shifted tom-toms with the shift in chords to produce a sensuous, rolling effect.

The second innovation was an electric guitar background which wavered in intensity. The chords seemed flowing and steady — not strummed.

The third crucial factor was Buddy’s voice. It defies explanation — the only way to know for sure is to hear the record.

“That little fact alone is probably the biggest factor that has kept Buddy Holly’s music alive for 16 years after his death,” said Norman Petty, who first recorded Holly and got him into the industry.

The influence of Buddy Holly and the Crickets was profound. Just look at the many known performers who capitalized upon the sound — Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Everly Brothers, Ritchie Valens, The Rolling Stones, Paul Anka, Neil Sedaka and Frankie Avalon, just to name a few. (Hear John Lennon’s cover of “Peggy Sue” here.)

Buddy Holly songs: Singing Peggy Sue on Ed Sullivan (1957)

Even though he was only in the spotlight for three years or so before his passing, Holly made a few appearances on television. Buddy Holly and the Crickets also appeared on the long-running Ed Sullivan Show, performing “Peggy Sue” on December 1, 1957.

This recording of “Peggy Sue,” then, is one of the few moving pictures we still have today of one of the original rock stars.

Buddy Holly’s career cut short 16 years ago (1975)

By Mike Wester, Lubbock Avalanche-Journal (Texas) February 2, 1975

“You say you’re gonna leave

You know it’s a lie

‘Cause that’ll be the day

When I die.”

A SINGLE-ENGINE four-seat air-plane took off from a Mason City, Iowa, runway into light snow and 35 mile an hour winds at 1:50 a.m. February 3, 1959.

The plane was headed for Fargo, N.D., but fifteen minutes after takeoff, the left wing tip grazed a cornfield five miles north of Clear Lake, Iowa. The plane plowed up hundreds of feet of earth and came to rest against a fence. No one heard the crash.

Pilot Roger Peterson and three rock ‘n’ roll stars were killed. The rock stars were Buddy Holly, “the unforgettable Texan;” Ritchie Valens, perhaps best known for his recording of “Donna,” and J.P. “Big Bopper” Richardson, famed for his golden record “Chantilly Lace.”

MORE: The day the music died: Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens & Big Bopper killed in plane crash (1959)

For Mr. and Mrs. L.O. Holley (Buddy changed his name to Holly after a printing mistake on his first record cover), it was not a musical legend which died in the crash, but instead, their youngest of three sons, a quiet boy with a dry sense of humor whose talent catapulted him to fame and death in two years.

MANY OF TODAY’S teenagers know little about the recording artist who may have done more in two years to change the nation’s style of music than any other individual before or since his time.

From June of 1957 — when his first record was released — until his death, Buddy Holly was one of the hottest recording artists in the world. The Buddy Holly list of hits includes “True Love Ways,” “Peggy Sue,” “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore,” “Words of Love,” “Not Fade Away,” “Maybe Baby,” “Heartbeat,” “Rave On,” “Raining in My Heart,” and perhaps his most famous — “That’ll be the Day.”

ALSO SEE: What style of car was hip in the fifties? See the 1958 Oldsmobile’s then-new look

Sitting in their music room at home, the Holleys tell the story of the singer who got his start singing country music at local high school dances. “He was so small that we usually sent his two older brothers to the dances just to make sure he didn’t get into trouble,” his father said.

The “music room” almost gives one the feeling of a small hall of fame, a memorial trophy room to the boy who practiced his guitar there, always with a tape recorder going so he could hear himself later.

A LARGE PORTRAIT of Buddy hangs on the wall above a rack of albums of recording stars who help make his music famous. On another wall is his sound equipment — stereo, tape recorder and speakers. His own albums line a third wall, and in the corner, below another gold record, is his guitar with a leather cover bearing his name.

There are 18 Buddy Holly albums containing 88 songs — of which 30 were written by Holly himself. Several of the recordings were released after his death by using tapes he made during practice sessions at home.

“We always knew Buddy was talented,” says his mother. “In fact, he won a singing contest when he was 5. But he put his music aside for a while, until he got his first guitar at the age of 14.”

He made a leather cover for the guitar, tooling it himself. The cover bears his name and the titles of the first two songs he wrote, “Love Me” and “Blue Days, Black Nights.” That’s the guitar the Holleys still have.

MORE: Elvis Presley joins the Army: 20 pictures of the King of Rock & Roll in uniform (1958)

Holly was young, eager and married only six months when he died. He was killed at the height of his popularity, which continues now through a cult that has quietly grown around his memory.

Buddy’s diamond watch was discovered in the snow in Iowa three months after the crash and a farmer returned it to the Holleys. Buddy’s father still wears the watch engraved with Buddy’s name on the back.

BORN CHARLES Hardin Holley on Sept. 7, 1936, he soon picked up the nickname of Buddy, one that stuck with him from preschool days until his death.

He is buried in Lubbock’s Municipal Cemetery, on the west side near a large, watching angel. His grave has a flat monument bearing the design of a guitar.

His wife still keeps close contact with the family, although she has since remarried. “We enjoy hearing from her from time to time, and each time we feel a little closer to Buddy,” said his mother.

Little will be made of Holly or his death in his hometown Monday, 16 years after his death. Two country and western radio stations will play Buddy Holly hits, and one will dedicate a two-hour show to Holly’s memory.

Fact, fiction and fable have blended over the years and it is difficult to learn how it all happened.

Many say Holly was just a little before his time, but his special beat of music turned the recording industry around and new sounds moved to the front and continued after his death.

BEFORE THE accident that ended his career, Holly had received two gold records for selling more than a million copies each — “Peggy Sue” and “That’ll Be the Day.”

About 5 million records had been sold before his death. Many millions more have been sold since and he continues to be among the top sellers both in America and abroad.

The music Buddy made is not dead. His sounds are still heard around the world. “Buddy’s fans have kept him alive for us,” his father said. ”Sometimes I slip into the room and play some of his albums, and it seems like Buddy’s right here with me.”

“You left me here so I could sit and cry

Well, golly gee, what have you done to me?

Oh well, I guess it doesn’t matter any more.”