Though Election Day became a formalized event in 1845, securing a predictable voting day, voter turnout remains an ongoing challenge. From logistical barriers to apathy, issues that keep people from the polls echoes from our earliest history all the way to today.

In the vintage article below, Mark Shields and Josiah Auspitz, political strategists, emphasized that democracy only functions when citizens participate fully. Their call to vote was a reminder that each ballot contributes to a collective voice. This message persists, as Americans are still called to bring their voices to the polls amid modern issues like long lines, restrictive polling hours, and, sometimes, a lack of faith in the system itself.

In honor of the ongoing importance of Election Day, we’ve reprinted an article from 1976, where Shields and Auspitz make the case for voting as an act of both pride and responsibility. Their insights show that Election Day is more than just an individual’s personal choice — it’s about strengthening the entire democratic process. This Bicentennial message still holds true, encouraging every eligible American to take part in shaping the country’s future by voting.

The case for voting this Tuesday (1976)

From Family Weekly magazine – October 31, 1976

Over half the nation’s registered voters are expected to stay home from the polls this year. The lessons of the Bicentennial taught us that the Colonists fought mightily to get the vote. Now it seems no one wants it anymore.

Josiah Lee Auspitz (a Republican strategist) and Mark Shields (a Democratic political consultant) are two members of the Committee for the Study of the American Electorate.

After taking a long look at the increasing alienation of the American voter, they’ve come up with some varied — and vital — reasons why, come Tuesday, you should head right for the ballot box.

Be an active participant in a self-governing society

By Josiah Lee Auspitz in the Sacramento Union (California) October 31, 1976

My mother once made the front page of a newspaper just by voting in a Congressional election. She was in the hospital recovering from major surgery, and on election day, ordered a private ambulance to take her across town to the polls.

A poll watcher alerted a reporter, who learned my mother was a recently naturalized US citizen from Czechoslovakia — a country whose elected leaders had been murdered in the Communist coup d’état of 1948.

Her act, the reporter concluded, was a testimonial to democracy. But most people told me my mother had foolishly risked her health for a “not very important” election.

In 20th-century America, there is no such thing as a “very important” election. The United States, as Woodrow Wilson remarked, is one country in which you don’t change the basic form of government by changing the man who heads it. Even when American elections mark fundamental turning points, they have more to do with continuity than with upheaval.

Voting is neither a way to change the world quickly, nor an act of protest. It certainly isn’t necessarily a sign of wholehearted approval of the candidates. At its heart, voting is neither more nor less than an act of civic affirmation.

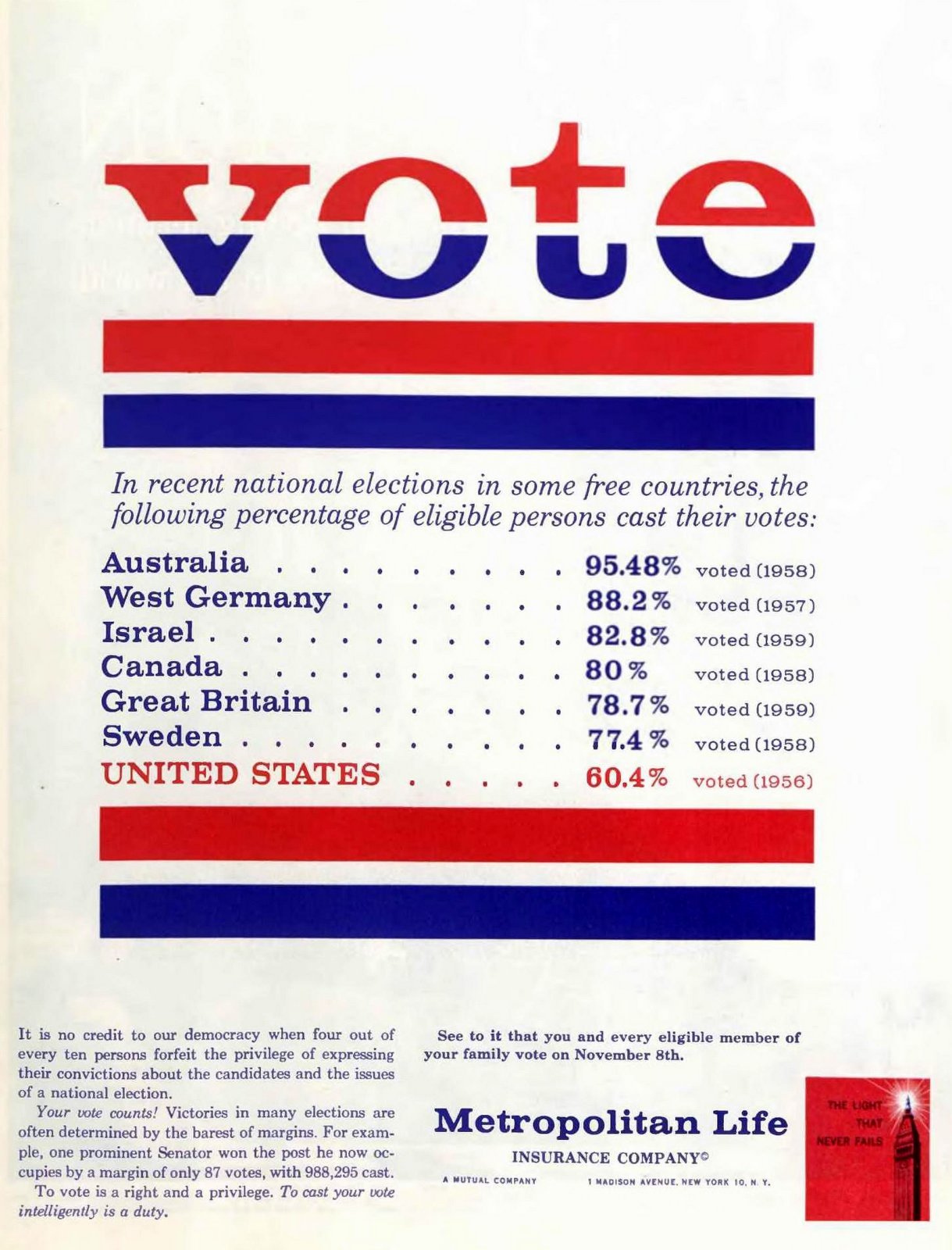

But in the United States, a smaller percentage of citizens votes than in any major democracy. Maybe you’ ve noticed that China and Russia have voting turnouts approaching 100 percent for their one-party elections.

And obviously, as long as American voting remains voluntary, turnout will be lower than in other countries. But too much nonvoting is a sign of a general apathy that goes beyond politics. In America, our nonvoter is less likely to attend church, to belong to a club, labor union, P.T.A., service or sports organization.

The person who says he will vote only when a good candidate comes along is the type who thinks he should only go to church when he has something specific to pray for.

A free country has a place for such people. But it will not remain free for long if their views predominate.

So there is a strong reason for voting regularly, even when one is not enamored of the candidates or has no great illusions about affecting the results: It is a way of affirming that one is an active participant in a self-governing society — a society free enough to allow people not to vote.

Don’t pass the buck – VOTE (1960)

Voting is your patriotic obligation (1976)

By Mark Shields in the Sacramento Union (California) October 31, 1976

If you’re one of the 145 million Americans eligible to vote, you’ve already been told that voting is your patriotic obligation, public responsibility, and personal privilege.

My case for your voting is simpler: Vote because it is in your self-interest and good for your self-esteem. Here are three reasons why:

1) In 1976, your vote will be very important. Since the end of World War II, there have been three national elections — 1948, 1960 and 1968 — which can accurately be called real cliffhangers.

In 1948, a shift of less than 30,000 votes (out of almost 49 million) would have given Tom Dewey the victory.

More than 68 million Americans voted in 1960. John Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon by a margin of only 118,574 votes.

Eight years ago, the contest was so close that if less than 125,000 voters had changed their minds — less than one vote per precinct! — our 37th President would have been named Humphrey.

In all likelihood, this election will be similar to those three. You and your vote will probably change history.

2) In 1976, you and your vote will count more than in any other election in your lifetime. On Election Day, according to a recent national survey, a majority of Americans eligible to vote may very well not vote. This means that our next President will almost certainly take office with the humbling knowledge that over 70 percent of his fellow citizens who could have voted for him did not do so.

Therefore, in this election, your vote will count more than ever — perhaps even twice as much.

3) The Government cannot govern without criticism.

Elected officials listen much more attentively to voters than to non-voters. So if you think there will be any time in the next four years that you may wish to disrespectfully dissent from any Presidential policy vote, it’s your political license to beef.