Delmonico’s during the Gilded Age helped turn fine dining into a spectacle

The original location opened in 1827 on William Street, with simple offerings like wine, cake and ices — but expansion came quickly.

A fire in 1835 gave the Delmonico family a chance to rebuild bigger and grander, with ballrooms, chandeliers and even pillars reportedly imported from Pompeii. That same year, hot food was added to the menu — and just like that, the modern American restaurant was born. The brothers and their savvy nephew Lorenzo kept up a reputation for elegance while also rewriting the rules of public dining.

By the 1860s, the Gilded Age had kicked in, and Delmonico’s was the place where New York’s newly rich went to put their names on the map. The restaurant’s move to Fifth Avenue at 14th Street matched the city’s uptown expansion and set the scene for a whole new level of extravagance. With formal dress codes, private dining rules and velvet ropes for social climbers, Delmonico’s offered meals with a side of exclusivity. The French-language menus were just the start — guests might also expect miniature yachts as centerpieces or nine-course meals served around a live swan pond.

Some of the most over-the-top dinners in American history took place within its walls. From truffled ice cream to whole banquets served entirely in paper bags, Delmonico’s didn’t shy away from spectacle. Dishes like Lobster Newberg and Baked Alaska are still associated with its name, as well as Manhattan Clam Chowder and Delmonico Potatoes. (Eggs Benedict and Chicken à la King may have also been the restaurant’s creations, but of these, the lore is less certain.)

Meanwhile, its catering division made headlines for pulling off events like a state dinner for the visiting Prince of Wales in 1860. Through it all, Delmonico’s kept a tight grip on decorum — even declining to allow couples to dine alone in private rooms.

The restaurant moved several times over the decades, each new location tracking the rise of Manhattan’s fashionable districts. Its final big move came in 1897, when it reopened at Fifth Avenue and 44th Street — right across from its closest rival, Sherry’s. The competition between the two became part of Gilded Age lore, with each trying to outdo the other in service, architecture and sheer social cachet. The company closed the restaurant at the Delmonico Building (on Fifth Avenue and 26th Street) in 1899, which led to the first story below appearing in newspapers nationwide. However, the name and its legacy has lived on in various revivals and reinterpretations in the meantime.

Below, we’ve collected a series of vintage photos, menus and newspaper articles that capture the peak Delmonico’s years — from the food and famous guests to the wild banquets that helped define a whole era. Check them out to see how one restaurant came to symbolize the most extravagant dining the Gilded Age had to offer.

Delmonico’s closed forever

The Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah) April 30, 1899

Memories that come with passing of the famous eating house

The closing of what was once known as “Uptown Delmonico’s” does away with the most famous eating house in the western hemisphere, and undoubtedly one of the best known in the whole world.

Delmonico came to this country seventy-two years ago, and in nine restaurants in New York has waged a constant battle against America’s national disease – dyspepsia. It was not always the same Delmonico who presided over the establishment, but the same traditions prevailed, whichever member of the family was there.

Though Delmonico’s has changed its location often, it has not changed its habits. What an interchange of experiences and expressions of emotions there must have been among the ghosts of the “Old Guards” Monday night as a gloomy waiter bowed out the last guest and closed the place forever!

It will no doubt give place to a skyscraper or a tailor’s shop or a saloon. Already real estate men are sniffing around it and calculating.

Delmonico’s menu from 1917

Party at Delmonico’s (1877)

New York City, the “flower party,” in aid of the Northeastern dispensary, given at Delmonico’s, Tuesday evening, April 3d [1877]

Party at Delmonico’s (1892)

Delmonico’s, drawn by Childe Hassam (From Century magazine)

Top photo: Looking south on 5th Avenue at 26th Street, showing Delmonico’s Restaurant, courtesy Museum of the City of New York; Images 2 & 3 courtesy the NY Public Library.

Don’t drop that name! Delmonico’s and Sherry’s old restaurants (1966)

By Ernest Leogrande in the Daily News (New York City, New York) November 6, 1966

Delmonico’s and Sherry’s pioneered the aura of where the elite meet to eat.

Delmonico’s — where live swans glided around a real pond in the center of the table…

Sherry’s — where guests dined on horseback and sipped champagne from saddle bags in a ballroom sodded with real grass…

They don’t hardly throw dinners like that in eateries anymore, and nobody seems to care much. The pressure is on and few people would be enchanted over beating a swan to the rolls or balancing a plate while keeping feet in stirrups.

That was the Age of Elegance and the all-night dinners and this is the Age of the Hamburger or the go-go scotch and soda.

The original Delmonico’s and the original Sherry’s are long gone, but the present management of the enterprises bearing those names by legal sanction have begun to work in their humble ways, they proclaim, to create a new sense of elegance amid the rat race.

The capitals of this Great Society fast-buck renaissance are Delmonico’s Hotel, 502 Park Ave. at 59th St., and the Louis Sherry restaurants at Lincoln Center. The very names of Sherry’s and Delmonico’s echo an old New York rivalry like the Giants and the Dodgers — fancier, maybe, but just as bitter.

Delmonico’s Hotel is operated by Joseph Tankoos Jr. and Elliot N. Yarmon, who took it over in 1962. Their early halting steps toward coping with the dizzy challenge of the past include flowers, champagne and chilled glasses automatically delivered on your arrival in any one of the 40 suites, getting your name in gold leaf on matchbooks if you stay more than two nights and Rolls-Royces provided for trips to and from the airports.

Besides its two plush restaurants, the hotel houses the Il Mio discotheque, a glittering cave of glass and youthful vitality.

Sherry’s at Lincoln Center operates the Rendezvous Cafe in Philharmonic Hall and the Fountain Cafe outside (in good weather). Without a doubt this must classify as New York’s most spacious sidewalk cafe.

At the State Theatre in Lincoln Center, Sherry’s operates a buffet on the promenade level and another fair-weather cafe tucked away in a corner outside.

In the Rendezvous, Sherry’s showoff spot, the waiters are jacketed in a rich, eye-blurring red and at times the service is almost self-consciously efficient. It’s as if the management is straining to counteract the residue of memories of the old Metropolitan Opera Sherry’s, where the decor had gone seedy and a patron couldn’t get to the bar at intermission without going through a personal version of the Immolation Scene from “Gotterdammerung.”

To tell the truth, the very first Sherry’s and Delmonico’s were not much more than eat-it-and-beat it joints. Sherry’s began as a small candy shop at Sixth Ave. and 38th St. in 1881. Delmonico’s was launched in 1827 as a confectionery at 23 William St. in what is now the financial district.

Eventually both establishments were to be temples of the elite facing one another across Fifth Ave. at 44th St., but there were a number of years before that titanic confrontation.

Delmonico’s was the forerunner in this fancy meal derby. Swiss-born John Delmonico was a seaman who plied between the West Indies and New York City. In 1825 he left sailing to set up a small grog shop at the Battery. About a year later he went back to Switzerland and told the family how easy it was to make money in the good old U.S.A.

He sold brother Peter on the idea and the two of them returned to open what is regarded as the first restaurant in New York City history.

It may seem incredible but up till then citizens ate their meals at home. The city still was centered around the present Wall Street section and the population hadn’t hit 300,000.

A working man either went home for lunch or carried it in his pocket. Taverns were popular places and at some of these you could get something called “the ordinary’ — a one-dish item. There was no choice of menu and if the tavern was out of the dish, you were out of luck.

On Dec. 13, 1827, Delmonico Brothers was opened at 21-23 William St., offering wine, cake and ices (that day’s equivalent of ice cream). French is one of the languages of Switzerland, which may be why the brothers listed their offerings in both English and French. It was a prophetically snobbish touch.

The room was small, with a dozen pine tables and suitable number of chairs crowded into it. The brothers wore white aprons and caps and offered white napkins with the food.

At first it was patronized mostly by young blades sneaking off from home on a weekend for a bite out despite dire parental warnings they would ruin their stomachs. As the cafe grew in popularity the brothers added hot food and that’s how the lunch away from home was born.

Four Delmonico nephews — Lorenzo, Siro, Francois and Constant — came over to help their uncles, who opened a branch at 76 Broad St.

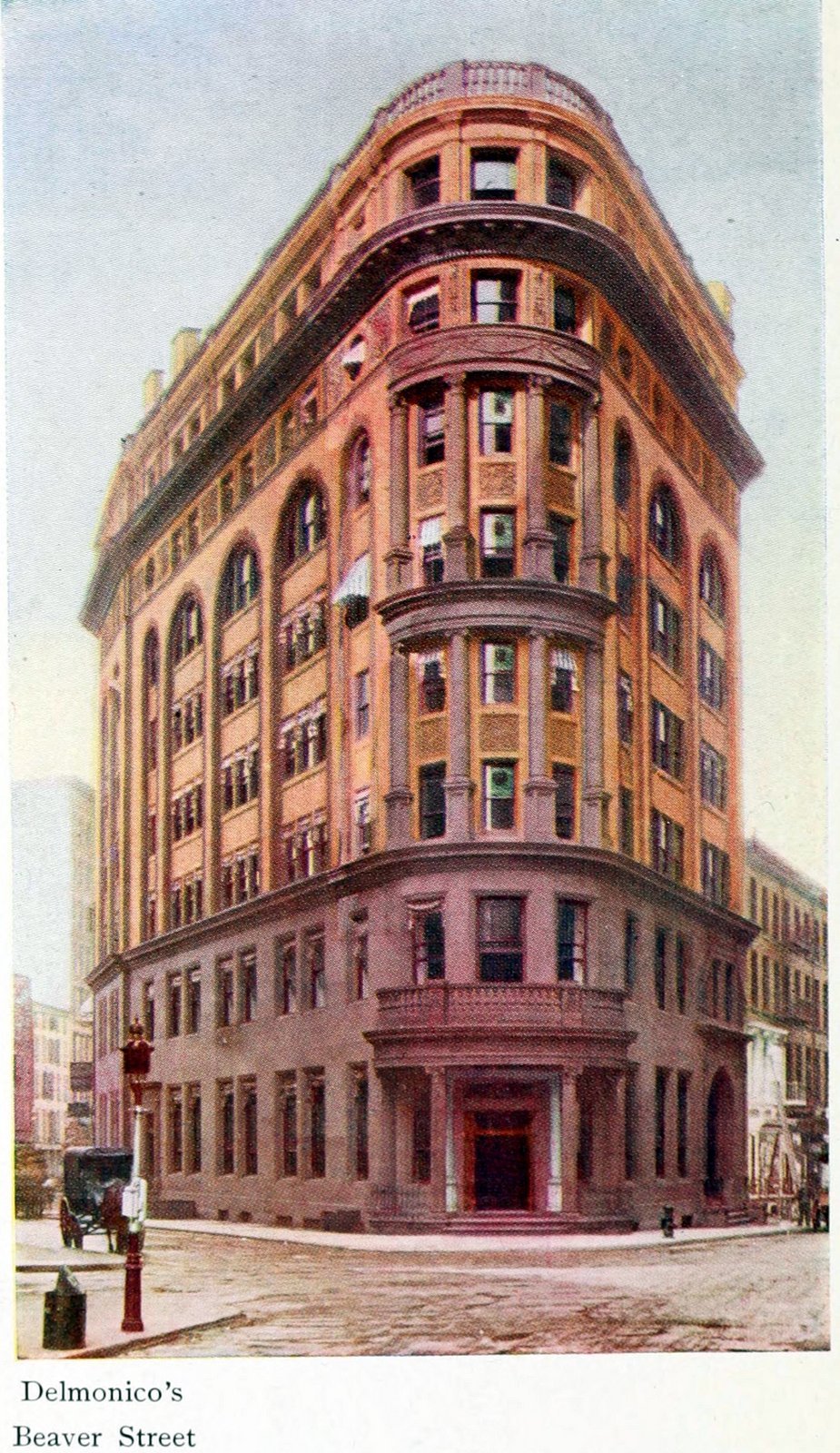

Lorenzo was a shrewd kid and when fire burned out the William St. place in 1835, he advised rebuilding on a larger site and making it more elaborate. The result was a three-story cafe and restaurant with ballrooms and lounges. The entrance was flanked by two marble pillars from the ruins of Pompeii.

This place, completely rebuilt internally, is known today as Oscar’s Delmonico, after owner Oscar Tucci, and is still at Beaver and William Sts. back there downtown.

The big city was still rustic enough to be flabbergasted by some of the Delmonico freres’ innovations. For instance, they actually used women as cashiers. For another their food wasn’t boiled or roasted within an inch of its life and was listed in a seven-page “Carte du Restaurant Francais” which offered nine kinds of soup, eight hors d’oeuvres, 15 kinds of fish, 11 beef dishes, 20 of veal, 29 of poultry, 18 of roast game, 18 vegetables (a real stunner; people weren’t partial to vegetables in those days), 16 kinds of pastry, 13 kinds of fruit and preserves and 62 kinds of wine.

The clan continued to open a place here and close one there, Lorenzo providing most of the savvy, but April, 1862, marks its real debut into the realms of glory.

The city was expanding, money was. flowing freely and Lorenzo arranged to buy a four-story mansion on the corner of Fifth Ave. and 14th St., then the center of uptown life. This was the beginning of American high living in public places, the flamboyant good time era recreated in today’s hit musical, “Hello, Dolly!”

Some of the nouveau riche names kicking around were Astor and Vanderbilt, and how does that strike you in the pocketbook?

A chap named Ward McAllister, who didn’t have much money of his own, but had a sense of elegance and the right connections, concocted something called The 400, which purported to list who was okay society and who wasn’t. He hoped this old guard would hold the fort against the onslaught of tawdry dollars. Money, naturally, triumphed.

Everybody who was or wanted to be anybody, locals or visitors from abroad, wanted to get into Delmonico’s at 14th Street. There wasn’t that much room.

Lorehzo had long since reinforced the snobbery of the French menu with the snobbery of choosing who was to be seated. For example, if you were royalty, you stood a pretty good chance.

If a man wasn’t desirable and he got in somehow, the management had a neat trick for getting him out. A waiter would come and take his order and not come back. If he got impatient and summoned another waiter, that one would take his order and not come back. Eventually he got the message.

Some of the moneyed customers might be robber barons and high-class kept ladies but in Delmonico’s propriety ruled. Men were forbidden to smoke in. the main dining room if ladies were nearby, and no woman was permitted to dine alone after dark. As the years went along, Delmonico’s yielded on these rules but it kept one hard and fast: no dinners for two in its private dining rooms. There had to be; at least three people; patently the management felt this would prevent any ” hanky-panky.

Big wheel August Belmont (Belmont money financed New York’s first sub- way line) once arranged a private dinner for himself and his wife and another married couple, Their guests got mixed up on dates and didn’t show. Belmont allowed as how he and his wife would dine alone in privacy anyway. No dice, said the headwaiter.

And they didn’t. Belmont stormed, but he and his wife ate and liked it in the main dining room under the safe chaperonage of all the other customers.

Catering for outside society affairs became a big Delmonico extra after it successfully carried off a catered dinner for the visiting young Prince of Wales, Queen Victoria’s son, in 1860.

One of these catered affairs proved a disaster. It was arranged by some New York families summering at Newport, which Mrs. Belmont had helped make a classy spa. When the flushed guests wandered in from the exertions of a cotillion on the lawn they found that the hired waiters had been locked in the cellar by party-givers’ own servants, who had gotten tipsy on the champagne.

There wasn’t a bit of solid food or a drop of wine left. Delicacies like that had never got as far as Newport and the poor things couldn’t restrain themselves.

That, of course, ended the party. One of the women commented on her coachman with admirable aplomb: “My man is beastly intoxicated, but I shall appear not to notice it.”

Conspicuous consumption became a game of one-upmanship. Some of the blowouts at the 14th St. Delmonico’s are summarized here:

- A yachtsman gave a party for 10, which cost him $400 a plate. At each place, in cut glass basins from Tiffany’s, there floated a miniature yacht with such niceties as satin sails and silk halyards.

- A visiting Englishman invited 100 New York tea and coffee merchants to a blowout where they sat on silk cushions and read menus printed in gold leaf on satin. A symphony orchestra played from behind a screen of potted palms. The tab was $20,000.

- At the “Swan Banquet,” as it came to be known, the table was so large the waiters just had room to pass the food. On the table, landscaped like a miniature woods, was a lake 30 feet long, sur- rounded by gold netting. Four swans sailed on the lake. Birds twittered in gold cages hung from the ceiling. A couple of the swans got into a fight, but the diners, undeterred, ate their way through all nine courses.

Not everyone ate at Delmonico’s in such Fun-City style, but some of the guests brought their own aura: Jenny Lind, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Oscar Wilde, Horace Greeley, Lillian Russell, Diamond Jim Brady, Louis Napoleon (later Emperor Napoleon III) and Presidents Lincoln, Grant and Johnson.

Over the years Delmonico’s offered a variety of exotica for the taste buds, ranging from truffled ice cream to a gimmicky dinner at which everything was cooked and served in paper bags, including the coffee.

Lobster Wenberg originated at Delmonico’s. It was created by a shipping line owner, Ben Wenberg, and became a standard on the menu. When Charles Delmonico, Lorenzo’s nephew, had a dispute with Wenberg, he didn’t order the dish canceled. He just changed its name to Lobster Newberg.

Following the progress of the city uptown, Delmonico’s moved to 26th St. and Fifth Ave. in 1876, and to 44th St. and Fifth in 1897, a location where it was destined to end its days, along with its great glaring rival across the street, Sherry’s.

As for Louis Sherry, he was born in St. Albans, Vt., in 1854. He left home at 14 to work in a Montreal hotel, then came to New York, where he got a job as a busboy and eventually a waiter at the Hotel Brunswick, near Delmonico’s.

After he had become famous, it was automatically assumed he was French. Actually, he used to boast, he learned French by talking with fellow employees. He never even went to Paris until he was 68.

Carefully, the lad saved his money and when he had $1,500 capital, he opened a candy shop at the corner of Sixth Ave. and 38th St. Society people on whom he fawned at the Brunswick threw their patronage to him and by 1887 Louis the First was making the trip up the avenue second.

He leased a mansion at the corner of 37th and Fifth and opened a restaurant and confectionery shop. Sherry’s became a society stomping ground, and many of its customers moved interchangeably between it and Delmonico’s. It acquired a reputation for being a little less stiff- necked about rules than Del’s (as the regulars referred to it).

One famous banquet held in 1897 helped to add immeasurably to this reputation, undeserved or not.

Herbert Barnum Seely, a rich young playboy, had told Delmonico’s he wanted to throw a bachelor dinner but he would have to have absolute privacy. This smelled too suspicious to be okayed. Turned away from Delmonico’s, Seely went to Sherry’s, where he got an okay.

The bachelor dinner spread included some dancing girls headed by Little Egypt, shaking it up in a more abandoned way than she had been allowed to at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. The police were tipped off and raided the * party.

One angry guest tried to throw the police captain in charge out a window, t he didn’t stop the raid, and there was plenty of subsequent newspaper publicity.

The blemish on Sherry was more than counter-acted by the ponderous sedateness of other famous parties. Two of the most notable occurred in its new home at 44th St. and Fifth Ave., where it arrived at about the same time as Delmonico’s, the two of them stumbling on each other’s heels.

Delmonico’s managed to get its doors open first, as its dazzler of a Renaissance-style building debuted Sept. 30, 1897, on the Northeast corner.

Architect Stanford White had to make sure he was designing Sherry’s new palazzo do right, so after some delay it opened Oct. 10, 1898, on the Southwest corner.

In the opinion of one newspaper of the time: “It will be a fight to the death” between the two “splendid new establishments, so near together that they can scowl at each other.”

Many people patronized both, but Sherry counted among his loyal supporters men like J. Pierpont Morgan and publisher Frank Munsey.

Sherry’s hosted the famous Horseback Dinner and Hyde Ball.

C.K.G. Billings, called the American Horse King, invited 36 cronies and fellow horsemen to dinner on a night in 1903. He ordered the grand ballroom of Sherry’s turned into a woods, which included a covering of rich green sod for the floor. These men, all in white tie and tails, dined astride horses brought up to the ballroom on freight elevators.

They ate from small tables placed across the horses’ flanks and drank champagne from saddlebags by sipping it through tubes. Toward the end of the banquet troughs of oats were brought out for the horses.

On the night of Jan. 31, 1908, James Hasen Hyde, first vice president of Equitable Life, turned Sherry’s into his $200,000 version of Versailles. Everyone came in fancy dress, the gentlemen in knee britches and the ladies laboring un- der powdered wigs and yards and yards of dress.

The party began at 8 P.M. and ended at 6 A.M. There was a recital by French actress Mme. Gabrielle Rejane, who was carried into the ballroom in a sedan chair, and some dancing, but mostly there was eating. In all, the company sat down to four different meals as the party wore along.

This was a common practice. As Jerome, Sherry’s longstanding doorman, reminisced years later: “Fating had precedence over dancing… at a ball of three hours duration, one danced for one hour and ate for two — stupendous banquets of eight and 10 courses calculated to produce lagging feet.”

Sherry’s — blaming ‘Prohibition and Bolshevism” — shuttered its doors as a losing proposition. On May 17, 1919, Louie took off for Paris and announced: “This is the nearest place to heaven I ever expect to see and I’m going to stay here until I die.”

In 1922, he came back and opened a new Sherry’s in an 18-story building at 300 Park Ave. He retired again shortly ate and died in 1926 in New York City.

Prohibition, high rent and changing tastes did for in Delmonico’s too. It closed on on May 21, 1923.

Don’t underestimate the value of a name. When Lucius Boomer, president of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel corporation, sold the old hotel site in 1928 for $13.6 million (the Empire State Building was built there), he reserved the right to the name.

In 1931, the new Waldorf-Astoria was built on Park Ave. between 49th and 60th Sts. and when Conrad Hilton got control of the operation for $3 million in 1949, he acquired more than a valuable hotel — he acquired a priceless name for the “queen” of his worldwide hotel chain.

Delmonico’s hotel opened in 1929, but it had no connection with the Delmonico family. What it did have was court permission to use the name. According to its builders, “The public regarded Delmonico’s as an institution which must not be allowed to disappear.” Ownership changed hands several times until Tankoos and Yarmon took over in 1962.

Tankoos is a real estate man with firm ideas about elegance. He re-christened the hotel Delmonico’s instead of Delmonico on the basis that the “-‘s” given the name that extra something.

“And please,” he said, “it’s Delmonico’s Restaurant, not dining room.” He thinks “dining room” smacks of an institution, not at all in keeping with the rose-colored atmosphere of his restaurant, where musicians play in a gazebo in the middle of the room, leaving it now and then to stroll among the diners.

The Sherry enterprise never really went out of business; it simply under- went changes of ownership. Last January the control of Louis Sherry, Inc., was taken over by Chicago grain heir Bruce Norris, 42.

With Louis Sherry, Inc., he inherited not only the restaurants at Lincoln Center but also the Louis Sherry candy, jam and jelly company in Long Island City and the Louis Sherry retail gourmet shops on Manhattan’s East Side.

New York can use all the elegance it can get these days, so don’t look for the old rivalry between these reincarnations of Delmonico’s and Sherry’s.

Sherry’s has a new rival of sorts. Another company — with the plebian name of Canteen Corp.– beat it to the restaurant franchise for Lincoln Center’s Metropolitan Opera, which means Sherry’s and the Met are no longer a duo after all these years.

But Sherry’s isn’t worried. It’s sure the concert and the light opera buffs at Philharmonic Hall and the State Theatre will be just as thirsty as the grand opera crowd.