Wireless aids in rescue works – Repeated calls heard by a half score of ships which hasten to the scene – the Titanic, the biggest most luxurious ship in the world, now lies at bottom of the sea

The Day Book. (Chicago, Ill.) April 17, 1912

“Sinking by the head and women are being rushed into the lifeboats!” were the last words that sputtered into the wireless room of the Virginian from the Titanic.

Wireless sounds distress cry

All through the night and until her wireless station was silenced, over hundreds of miles of sea from the antennae of the giant liner flashed the mystic and magic “SOS,” — the worldwide cry of distress on the ocean.

Every wireless operator within range of the maimed vessel dropped her other message to locate her and meanwhile relayed the fatal message to the world.

The collision occurred in latitude 41.46 north and longitude 50.14 west, 1,150 miles east of New York and 450 miles south of Cape Race, the most westerly point of New Foundland [sic].

No storm prevails

Contrary to earlier dispatches there was no storm when the vessel struck. The weather was clear and calm.

Almost as soon as the Virginian picked up the distress signal, it was recorded by the operator on the Olympic, the Titanic’s sister ship. and next to her the largest vessel afloat. This was at midnight. At that hour, the Olympic was 200 miles from New York en route to Southampton.

The Olympia forged ahead under full steam, but wireless dispatches indicate that she reached the scene too late to be of any assistance.

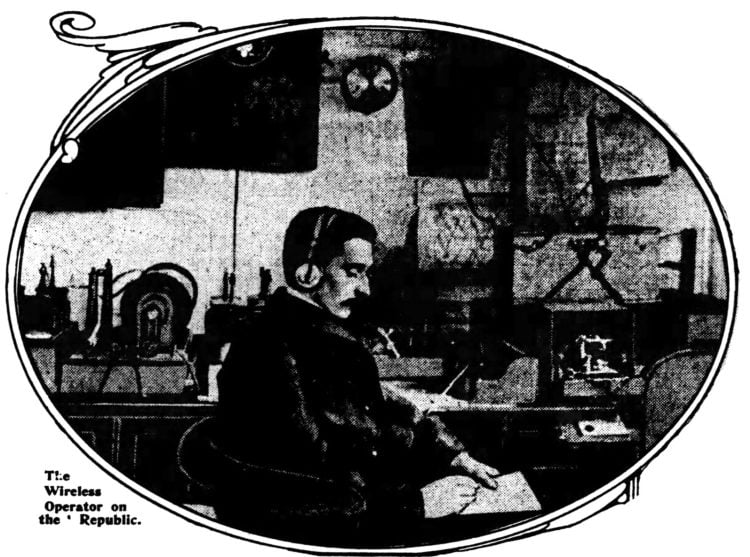

Titanic SOS messages: Story in pictures of how wireless waked the midnight sea

Although the steamer Titanic sank before help arrived, one of the most remarkable features of the disaster was how the great liner’s dying call for help by wireless telegraphy awakened the midnight sea. “S. O. S.” (Send out Succor) flashed out over the silent wastes shortly before 11 o’clock.

Every few minutes, the airwaves carried “S. O. S.” until 12:17, when it stopped. But in that hour and a half, the cry for help was picked up by a dozen ships — ships that turned from their courses and sped under forced draught to the spot in old ocean where grim tragedy was at work. The picture illustrates how the sea responded:

Titanic SOS messages: The last wireless messages: CQD & SOS

Here are some of the wireless messages sent and received by the Titanic after the iceberg was hit, and up until a few minutes before she sank. Note: CQD is a distress call — not actually an acronym for “Come quick – Disaster” or anything else.

All of these messages were sent on April 15, 1912, and began shortly after midnight.

12:17 am — Titanic to Any Ship: “CQD CQD SOS Titanic Position 41.44 N 50.24 W. Require immediate assistance. Come at once. We struck an iceberg. Sinking.”

12:20 am — Titanic to Carpathia: “Come at once. We have struck a berg. It’s a CQD, old man. Position 41.46 N 50.14 W”

12:25 am — Carpathia to Titanic: “Shall I tell my captain? Do you require assistance?”

12:26 am — Titanic to Carpathia: “Yes, come quick!”

12:32 am — Carpathia to Titanic: “Putting about and heading for you”

12:40 am — Titanic to Carpathia: “SOS Titanic sinking by the head. We are about all down. Sinking. . .”

12:50 am — Titanic calls CQD — “I require immediate assistance. Position 41.46 N. 50.14 W.”

1:30 am — Titanic tells Olympic, “We are putting passengers off in small boats.” “Women and children in boats, can not last much longer”

1:35 am — Olympic asks Titanic what weather she had. Titanic: “Clear and calm”

Between 2:15 am and 2:25 am — Titanic to Carpathia: “SOS SOS CQD CQD Titanic. We are sinking fast. Passengers are being put into boats. Titanic.”

Titanic repeatedly warned of icebergs by Parisian’s operator

The Washington Times (Washington, DC) April 18, 1912

[Wireless operator] Donald Sutherland tells graphic story of floating ice, and of his constant messages to the Titanic — Night was clear and starlit, he says — Believes Captain Smith must have known of danger.

With one expedition leaving this port today to search for the Titanic dead and another preparing to leave tomorrow, the Allan steamship Parisian crept through the fog to her dock tonight hearing the first big authentic news known of the stupendous tragedy of the sea.

The great glaring fact, as given by Donald Sutherland, the wireless operator of the Parisian, was his unqualified statement that the night of the disaster, judged from the position of the Parisian, which he estimates to have been about fifty miles southwest of the Titanic at the time she struck, the weather was remarkably clear. In all the course through the day no fog had been encountered.

“The night was so clear,” said Sutherland, “that the Parisian’s lookout several times mistook stars on the horizon for ship’s lights. You have seen beautifully clear winter nights when you went skating and it seemed just like day. It was just such a night you could have played a game of football.”

And what is more, Sutherland says that from his instrument through most of the evening he was sending out warnings to other ships as to the unusual condition of ice floes in the usual winter course of Atlantic travelers.

“All navigators agree that the condition was unusual, that constant north-easterly gales had driven ice hundreds of miles further south than is usually to be expected at this time of the year. Usually, the greatest danger from derelict bergs is to be found in May and June, and even as late as July in the trans-Atlantic avenue in which the Titanic was passing.

Sutherland says that while he has no positive information, he is sure the warning that he and other wireless operators sent out must have reached the Titanic. He said:

“On Sunday, the 14th, I was at my instrument until 10 o’clock at night. The Masaba of the Atlantic Transport line was ahead of us. The Californian was about fifty miles in our rear and the Titanic was following the Californian at a distance, I judge, of 75 to 100 miles.

“The Masaba was passing me warning messages about the unusual icy condition of the course and warned me of the presence of big bergs, I passed the information to the Californian. I sent this message repeatedly: ‘Running into ice — very thick — and big bergs.”

“I assume, although I do not know, for I did not talk directly to the Titanic that the Californian passed to the Titanic the messages I had sent and which I had myself previously received from the Masaba.

But next morning, when we were fifty miles further south of our course than the Parisian had ever before gone, our route being between Glasgow and Boston, with Halifax as a port of call, and we were on our way to Halifax, but, of course, had to dig southward to escape the ice line I got a wireless from the Asian stating that she had picked up the Deutschland, and so we have come on to Halifax.

“I left my instrument at exactly 10 o’clock. I was ordered to do so by Captain Hains because I had been up many hours in an effort to get a ship to go to the aid of the tank steamship Deutschland, which I had heard was in distress.

“The Deutschland had no wireless, so I could not get into direct communication with her, but our information was that she was pretty far to the south, and Captain Hains was heading in that direction as fast as he could go. He wanted me to get on the wireless at 4 o’clock next morning and do what I could with the wireless to discover if possible what news was crossing the sea regarding the Deutschland.

“I received a query on the night of the disaster from Captain Haddock, of the Olympic, the Titanic’s sister ship, traveling east, as to the condition of the ice, and I sent to him the same message that I had relayed from the Masuba to the Californian, and that, of course I believe was as promptly relayed to the Titanic: ‘Running into ice — very thick — and big bergs.’

“I want to add,” said Sutherland, who is about thirty years of age, “that I have been traveling on this course for seven years and there has never been in my experience such a condition of the ice as we found on this voyage. The floes have come extraordinarily early and have spread way out of the usual run of what is known as the ice belt.

South of ice line

“Certainly the Titanic when struck was far south of what the chart defines as the ‘ice line.’ She was fully 75 to 100 miles south of it.”

A report that the Parisian had picked up survivors of the Titanic and had then passed them to the Carpathia proved to be untrue.

“The first news of the disaster I got about 10 o’clock on Monday morning from the Carpathia,” said Operator Sutherland.

When he was asked just what this message from the Carpathia was the wireless operator replied that he could not reveal it. He said it was confidential in nature and intended only for the ears of Captain Hains, of the Parisian.

There had been a theory advanced that a berg of the size that could send the Titanic to destruction might on a clear night throw out of its own humidity so great a haze as to enmesh mariners in a fog for a mile or more. Sutherland was asked as to this out of his own experience. He said it was absurd, and exclaimed:

“Why, on a clear night you can see a berg away off by its glitter. They glisten like an illuminated glass palace.”

Captain Hains said: “There is no question that the course used at this time of the year was never so invaded by ice in the knowledge of even the most experienced seamen it has been extraordinary the truth is that northeasterly gales began very early last winter and were almost continuous. The result has been to drive the ice hundreds of miles further south than is usual.

“Moreover, in the swift drive of the great current from the north, bergs shot off the turn that it takes off the Breton coast as mud might fly from a wheel, and these bergs by the score got into a course usually considered free of such dangerous impediments at this season of the year.”

One Response

I would like more information but otherwise a great webpage on this particular SU just! I have quite a amount of sympathy and empathy so this article brought me to tears. <3