Born in London in 1889, Charlie Chaplin’s early life was anything but glamorous. Raised in poverty, he found an escape in performing, following in the footsteps of his parents, who were both entertainers. By the time he was a teenager, Chaplin had honed his comedic talents on the vaudeville stage, and it wasn’t long before Hollywood came calling. His transition to film brought the world his beloved character, the Little Tramp, whose quirky charm and resilience in the face of adversity made him an international sensation.

Chaplin’s impact wasn’t limited to his ability to make audiences laugh. He was also a trailblazer behind the scenes, taking on roles as writer, director and composer for many of his films. His work in The Kid (1921), City Lights (1931), and Modern Times (1936) showcased not just his comedic genius but also his deep understanding of the human condition. Chaplin’s films were often laced with social commentary, making them both entertaining and thought-provoking, a combination that few filmmakers have managed to achieve with such finesse.

As time passed, Chaplin faced challenges, including political controversies and changing public tastes. However, his contributions to the art of filmmaking remain unparalleled. His ability to tell stories without uttering a single word — yet conveying universal themes of love, hardship and joy — has solidified his place as a cornerstone of cinematic history.

Below, learn more about the man behind the mustache! We’ve compiled a collection of vintage materials that explore his life and legacy, including a reprint of a detailed 1915 article that dives into the early days of Chaplin’s career as well as vintage profiles and photos that offer a deeper understanding of how Chaplin became a film icon.

No contribution to “movie” literature has created so much interest among film “fans” as this simple, straightforward account of the life history of the world’s most famous comedian.

Charlie Chaplin’s life story, Part I

As narrated by Mr Chaplin himself to Harry C. Carr – Photoplay Magazine, July 1915

I am going to reconstruct, as far as possible, Charlie Chaplin’s story just as he told it to me, in various little lulls and calms between pictures, or baths, or dinner engagements, or whatever seemed to be coming interferingly between us.

I found him a quiet, simple, rather lovable little chap, with no especial ambition except to be of entertaining service to the world.

He balked at the idea of writing his own autobiography or having it written “to sign;” said he’d read fifty autobiographies of more or less well-known people which were just full of words which they’d never heard in their lives, so what was the use? But as I said, I will endeavor to tell his story as nearly in his own words as I can:

Actors trying to write autobiographies are like girls trying to make fudge. They use up a lot of good material — such as sugar and ink — and don’t accomplish much.

Like fudge, the story of a fellow’s life ought really to be reserved for his immediate relatives. If I were Lord Kitchener, doing things and saying things that made history, I could understand why the story of my life ought to be written; but I am just a little chap trying to make people laugh.

They are all so anxious to be happy that they eagerly help me make the laughs — the audiences, I mean. But they give me all the credit — not taking any themselves for being so willing to laugh.

So I feel, in a way, that in telling this story, I am just talking it over with my business partners — the end of the firm that really makes the laughs.

Some day, when I have made money enough out of my share, I am going to buy a little farm and a good old horse and buggy — automobile agents can read this part twice — and retire; sometimes I will ride into town and go to a moving picture show and see some other fellow making them laugh. In the circumstances, I guess you can just put this story down to this: that Charlie Chaplin gives an account of himself to the firm.

Chaplin on his career goals as a boy

When I was a little boy, the last thing I dreamed of was being a comedian. My idea was to be a member of Parliament or a great musician. I wasn’t quite clear which. The only thing I really dreamed about was being rich. We were so poor that wealth seemed to me the summit of all ambition and the end of the rainbow.

Both my father and mother were actors. My father was Charles Chaplin, a well-known singer of descriptive ballads. He had a fine baritone voice and is still remembered in England.

My mother was also a well-known vaudeville singer. On the stage, she was known as Lillie Harley. She, too, had a fine voice and was well known as a singer of the “character songs” which are so popular in England.

She and my father usually traveled with the same vaudeville company, but never, as far as I know, worked in the same act. In spite of their professional reputations and their two salaries, my earliest recollections are of poverty. I guess the salaries couldn’t have amounted to much in those days.

My brother Syd was four years old when I was born. That interesting event happened at Fontainebleau, France. My father and mother were touring the continent at that time with a vaudeville company. I was born at a hotel on April 16, 1889. As soon as my mother was able to travel, we returned to London, and that was my home, more or less, until I came to America.

Singing on stage in a vaudeville act

The very first thing I can remember is of being shoved out on the stage to sing a song. I could not have been over five or six years old at the time. My mother was taken suddenly sick and I was sent on to take her place in the vaudeville bill. I sang an old Coster song called “Jack Jones.”

It must have been about this time that my father died. My mother was never very strong, and, what with the shock of my father’s death and all, she was unable to work for a time. My brother Syd and I were sent to the poorhouse.

English people have a great horror of the poorhouse; but I don’t remember it as a very dreadful place. To tell you the truth, I don’t remember much about it. 1 have just a vague idea of what it was like. The strongest recollection I have of this period of my life is of creeping off by myself at the poorhouse and pretending I was a very rich and grand person.

My brother Syd was always a wide-awake, lively, vigorous young person. But I was always delicate and rather sickly as a child. I was of a dreamy, imaginative disposition. I was always pretending I was somebody else, and the worst I ever gave myself in these daydreams and games of “pretend” was a seat in Parliament for life and an income of a million pounds.

Sometimes I used to pretend that I was a great musician, or the director of a great orchestra; but the director was always a rich man. Music, even in my poorhouse days, was always a passion with me. I never was able to take lessons of any kind, but I loved to hear music and could play any kind of instrument I could lay hands on. Even now, I can play the piano, ‘cello or violin by ear.

Syd had a lofty contempt for these dreams of mine. What Syd wanted was to be a sailor. He was always pretending he was walking the bridge of a great battleship, ordering broadsides walloped into the enemy’s ships of war.

We didn’t stay long at the poorhouse. I am not sure just how long, but my impression is of a short stay. My mother recovered her health to some extent and took us back home.

Syd went away from home immediately after we left the poorhouse. He was really very anxious to be a sailor, and my mother sent him to the Hanwell school, in Surrey, where boys are trained for the sea. Many boys from the poorhouse went to this school. I dare say that is where Syd got the idea.

ALSO SEE: Burns & Allen: The story of world-famous comedy duo George Burns & Gracie Allen

In school in London

My mother sent me to school in London, I don’t remember a great deal about it. The strongest recollection I have of school is of being rapped over the knuckles by the teacher because I wrote left-handed. I was fairly hammered black and blue on the knuckles before I finally learned how to write with my right hand. As a result, I can now write just as well with one hand as the other.

On account of the random way we lived, I didn’t go to a regular school very much. Whatever I learned of books came from my mother.

Mother “the most splendid woman”

It seems to me that my mother was the most splendid woman I ever knew. I can remember how charming and well mannered she was. She spoke four languages fluently and had a good education. I have met a lot of people knocking around the world since; but I have never met a more thoroughly refined woman than my mother.

If I have amounted to anything, or ever do amount to anything, it will be due to her. I can remember very plainly how, even as a very small child, she tried to teach me. I would have been a fine young roughneck, slamming around the world as I did, if it not had been for my mother.

I don’t remember ever having had any definite ambition to go on the stage or of being attracted to the life. I just naturally drifted onto the stage, just as the son of a storekeeper begins tending to the counter.

Near-drowning

With both my mother and father, however, it was a definite intention to put me on the stage. I can’t remember when the talk of this began. It always seemed to be a fact generally understood in the family that I should be an actor. I can remember how carefully my mother trained me in stagecraft. I learned acting as I learned to read and write.

I don’t remember when I began regularly as a professional, but I remember that I was already working on the stage when I had a narrow escape from drowning.

I remember that I was on tour with a show called “The Yorkshire Lads.” It seems to me that I could not have been much over five or six years old; but I suppose I must have been a year or two older. Two or three of the boys of the company were throwing sticks into the River Thames, and I slipped into the stream.

I can remember how I felt as I was swept down the river on the current. I knew that I was drowning, when I felt a big, shaggy body in the water near me: I had just consciousness and strength left to grab hold of the fur and hang on, and was dragged ashore by a big black woolly dog which” belonged to a policeman on duty along the river. If it hadn’t been for that dog, there wouldn’t have been any Charlie Chaplin on the screen.

I don’t remember anything about the show I was acting in at that time. I suppose I must have been acting or singing at intervals during those years, but the first show I have any very definite recollection of was a piece called “Jim, the Romance of Cocaine,” by H. A. Saintsbury, who is a very famous playwright on the other side.

This was my first real hit on the stage. I had a part called “Sammy, the Newsboy,” and I will have to admit that between the part and myself we made a terrific hit. I got some line notices from the big London newspapers, and from that time I began to go ahead.

I liked playing a regular part much better than I did the vaudeville work. It seems to me that I had made up my mind at this time to become a legitimate actor. I don’t remember that comedy appealed very much to me, either.

I think my parents both had the same ambition for me that I had for myself. My vaudeville work with them was only incidental. Both parents being in vaudeville, it was very natural that I should occasionally be used in one capacity or another in the show. This is the almost invariable fate of children of the vaudeville. But as I remember my mother’s training, it was all looking toward a career for me as a legitimate actor.

The next important part I remember, after appearing as Sammy the newsboy, was in “Sherlock Holmes,” in which I had the part of Billy. I toured all over England in this part and did well.

After this, I began to encounter what Americans call “hard sledding.” The worst period in the life of an actor who starts as I did is the period between boyhood and maturity. I had a hard time getting along then. I was too big to make boys’ parts convincing, and too small and immature to take men’s parts.

I will reserve for another chapter my real start as a grown up actor.

Boyhood sweethearts

It seems that the story of nobody’s boyhood is complete without the account of his boyhood sweethearts. I am afraid I have nothing thrilling to tell in this regard. I was not the type of boy who was very strongly attracted to girls in real life. I was too busy with the people of my games of “pretend.”

Most of my boyhood sweethearts were wonderful creatures of my daydream. I have a vague recollection of certain wonderful charmers of my own age; but it is not quite clear in my own mind which were the real little girls and which were the dream children. The little boy-girl flirtations never appealed to me. The young ladies available did not live up to the standard of grandeur set by the young ladies that I imagined.

If, in some way, I have relegated to the mist of unreality some little girl whom I really adored and whose name I have forgotten to her I present my profound apologies. I will fall back on slang and say that she was a dream anyhow, which ought to square it.

Charlie Chaplin’s life story, Part II – His stage career and movie beginning

By Harry C. Carr – Photoplay Magazine, August 1915

AFTER he became old enough to be a “regular actor,” Charlie Chaplin didn’t find the going very easy.

The irony of his fate was that, after all his training by his mother for the career of a legitimate actor, the only direction in which he really scored was in rather rough comedy. His success, however, was in the quaint touch that he brought to what had formerly been pointless horseplay.

Chaplin tells his friends that he knocked around from pillar to post on the stage in England — sometimes in one job, sometimes in another. He says that he was glad to eke out a bare living. Most of the time he was working in burlesque and pantomime. He ascribes his success in the pictures to the early training that he got under the great English pantomimists.

About 1910, Fred Karno put on a variety act called “A Night in a London Music Hall.” It concerned the adventures of a very badly spifflicated young swell in a box at a music hall.

The stage was set for a miniature music hall with the boxes at one side of the stage. The tipsy young swell sat in one of these boxes. He tried to “queen” all the beautiful ladies on the music hall vaudeville bill.

Several times he climbed over the edge of the box onto the miniature stage. Most of the time, he was either falling into or out of the box. The swell had to do about a million comic “falls” during the progress of the sketch. It was very funny and ended in a riot of boisterous mirth.

In England, the part of the tipsy young person was taken by Billy Reeves, a well-known comedian who is now with the Universal Film Co. The sketch made such a hit that Karno finally decided to send it over to the United States. Reeves proved to be a riot here and Karno organized and sent over a No. 2 company to tour the Western States. Charlie Chaplin was employed to head the No. 2 company. His salary was $50 a week.

Chaplin often tells his friends of his adventures when he first arrived in the United States. It is enough to say when he first looked upon us as a nation, he decided that he would not do. He didn’t think anything of us that we would enjoy remembering.

Chaplin says that shortly after arriving in New York, he went to a show in a vaudeville theatre. It happened that some vaudeville actor was giving an imitation of an English swell — or at least what he thought was an English swell… a regular Bah Jove one… one of those remarkable creations, the like of which really never lived on the earth. Chaplin, who is a very serious young person, was deeply offended.

To say he was peeved at this reflection upon his countrymen is patting it mildly. As the sketch went on, Charlie got so indignant he couldn’t stand it any longer. He rose in his seat and started a public protest.

He never got any further than “Oh I say there,” when some of his loving friends grabbed him and removed him from the place before the janitor got a chance to cave in his now celebrated countenance.

MORE: Hanging from a clock, Harold Lloyd made movie history in ‘Safety Last!’ (1923)

Charlie likes America now. He confesses that he finally returned to England at the head of his No. 2 “Night in a Music Hall” company and found that he had outgrown England. Also, England had outgrown him.

He cheerfully admits that England couldn’t see him at all. The English are peculiar as theatre audiences. They cling to the old favorites and resent newcomers taking their places.

So Charlie, after vainly tumbling around on the stages of his native land, exclaimed to his companions, “For God’s sake, let’s get back to the United States where they know about us.”

Chaplin’s western tour was a huge success. He played the Sullivan and Considine Circuit on the Pacific Coast. To tell the truth, he was simply a riot. In Los Angeles especially, he made an immense hit.

The word flew around the “wise alleys” to “go over to the Empress and see that drunk. He’ll kill you sure.” Chaplin made a special hit with other theatre people. His rough comedy had in it a touch of real thought and superiority and earnestness that was recognized as something different. Every drunken fall showed the planning of a fine brain.

Owing to the manner in which the word was passed around among theatre people, Chaplin was well known to actors and to moving picture people around the studios of Los Angeles for sometime before he went into the business.

The year after he played his “Night in a London Music Hall,” he came back to the Western States in another sketch called “The Wow Wows.” In this he again took the part of a swell drunk. In fact, all Chaplin’s early successes were drunken “dress suit comedies.”

The “Wow Wows” was only fairly well received and the following years he came out again in the “London Music Hall.”

By this time, his sketch had become one of the most famous in ten-twent-thirt vaudeville. During this third year, some one of the Baumann and Kessel people who own the New York Motion company conceived the idea of getting Chaplin to come into moving pictures. Mack Sennett, who heads the Keystone Comedy Company was consulted and approved of the idea. He was delegated to sign up Chaplin.

Chaplin was then getting $75. Sennett called on him at the Empress Theatre and offered him a prodigal raise; he offered Chaplin a year’s contract at $175 a week. Chaplin was nearly scared to death.

A Los Angeles friend tells about it: “One night, Charlie stopped me on the street and told me about the offer. He was excited and didn’t know what to do. He said he was afraid to try as he didn’t think he would make good. The money, though, was a terrible temptation. He filled and backed for a while, but finally decided to sign.

He was largely influenced to do this by the contract. I remember that he kept saying, “Well, you know they can’t fire me for a year anyhow. No matter what a flivver I make of it, they will have to pay me my salary for a year anyhow.”

Charlie played out his vaudeville engagement and went out to the Keystone. He felt about as sure of himself as a man going up in a flying machine.

To make this story right, our young hero should have gone out to the Keystone and scored a triumph — but, alas, the facts are against him.

His first days at the Keystone were anything but happy ones. They didn’t understand him, and he didn’t understand them. Chaplin had been carefully trained along the lines of English pantomime.

He found the silent drama a la American to be utterly different in every particular. They didn’t get effects the same way. American comedy was, in those days, a whirlwind of action without any particular technique. Charlie was more shocked than he had been at the vaudeville actor who mocked his countryman.

From all accounts, he and the lovely Mabel Normand, now the best of friends and the warmest admirers of one another, got along about as well as a dog and cat with one soup bone to arbitrate. He told Mabel what he thought of her methods and Mabel told him a lot of things. In those days, Charlie used to come wandering back of the scenes at the theatres as lonesome as a lost soul. He was ready to chuck the whole business.

“They won’t let me do what I want; they won’t let me work in the way I am used to,” he complained.

His first pictures for the Keystone were not much of a success. In one of them he appeared in the part of a woman. Chaplin was a misfit in the organization. The directors couldn’t understand his particular style of comedy and things were going very badly. Chaplin did not fit into the Keystone comedies. A play has to be especially built up to Chaplin’s style.

Chaplin was a very likeable chap, however, and was very popular with the other actors. He was modest to a fault; they liked him because he didn’t try to hog either the film or the scene. Also in a shy way, he taught them a lot.

In those early days, the art of the comic fall was not well understood. The Keystone policemen were half the time in the hospital. Actors suffered more casualties than the German army. Chaplin had had a thorough training in “falls” from the trained English pantomimists. He knew exactly how to do it. He very generously passed on this knowledge to the sore and suffering Keystone police force. The hospitals were the poorer thereby.

Also, the Keystone people began to see there was something in Chaplin’s methods worth studying. Chaplin, on the other hand, began to adopt the American film methods.

He never made a real success however, until Mack Sennett let him direct his own comedies.

Sennett is a very keen judge of character and he saw that if anything was to be had out of Chaplin, it must be had in Chaplin’s own way. He reconstructed the organization to enable Chaplin to direct his own comedies.

Sennett’s decision brought into being the quaint character with the little stubby mustache, the big shoes and the cane that is known wherever motion pictures are known.

Chaplin’s first picture with the Keystone company was a little comedy sketch called, “A Film Johnny.” It was taken at the first cycle car races given in southern California. Chaplin had the part of a picture fan who was always wandering out in front of the cameras that were trained on the race. His part was merely intended to “carry” the motion pictures of a race.

A good many of Chaplin’s earliest pictures with the Keystone were of this character: he was used to put in incidental business in big news events. In one news picture taken at San Pedro Harbor, for instance, he was assigned the part of a roughneck woman who was very severe with her husband.

The first picture that he directed himself was called “Caught in the Rain.”

As a director, Chaplin introduced a new note into moving pictures. Theretofore most of the comedy effects had been riotous boisterousness. Chaplin, like many foreign pantomimists got his effects in a more subtle way and with less action. Also he worked alone to a greater extent than any other picture comedian.

By making the most of the little subtle effects, Chaplin enlarged the field of all motion picture comedies. It goes without saying that the simpler effects a man needs for his fun-making the more effects he has to draw on.

One of the very funniest situations, for instance, in any of the Chaplin comedies was in “His Trysting Place,” where Chaplin used the whiskers of a guest in a cafe for a napkin.

Charlie Chaplin’s life story, Part III: Through disappointment to world fame

By Harry C. Carr – Photoplay Magazine, September 1915

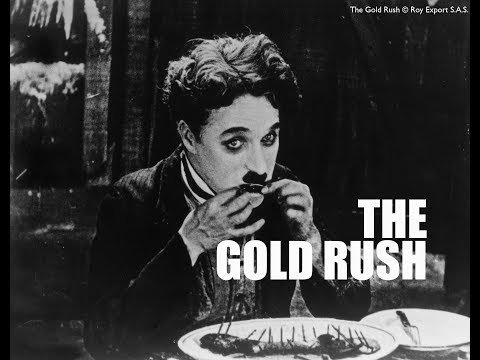

THE question that nearly everyone asks about Charlie Chaplin’s early career is “Where did he get that make-up? Those shoes and that hat?”

The general impression is that Chaplin worked with this same outfit from the beginning of his picture work, but this is not true. In his first pictures for the Keystone, Chaplin wore a long drooping mustache and a top hat. He wore ordinary shoes. In almost his first pictures, however, he began wearing the amazing “pants” that still disadorn him.

His first costume didn’t suit him at all. The Keystone people say he was always poking around the property room trying to hit upon some sort of clothes that would “register.”

One day he came out grinning, with a funny old pair of shoes in his hands. They were long and curled up at the toes. They reached right out and shook hands with Chaplin as soon as he saw them. They had been Ford Sterling’s and had been left behind when Sterling quit the company.

Chaplin has worn those identical shoes ever since. Then he began trimming off his long drooping mustache. Every day it grew shorter until it was finally the little toothbrush that is now so famous. He then substituted a round derby for his top hat and his costume was complete as it now appears in his pictures.

His costume was not the only difficulty he found in getting adjusted to the movies. To tell the truth, he was miserably unhappy at first, and hated the work in every way. Ford Sterling had just left the company and it was hoped that Chaplin would take his place. They naturally looked to see Chaplin work on the same lines as the comedian they had lost.

Chaplin, however, worked on entirely different methods. Sterling worked very rapidly, dashing hither and thither at top speed. Chaplin’s comedy was slow and deliberate and he made a great deal out of little things — little subtleties. They tried to force him to take up the Ford Sterling style and Chaplin refused. That is to say, he wouldn’t. He just listened to what they had to say; then did it in his own way.

The net result was a very sultry time, Chaplin’s first director was Pathe Lehrmann. They quarreled all the time during the first of Chaplin’s work. Mabel Normand and Chaplin fought like a black dog and a monkey.

Lehrmann finally appealed to Mack Sennett: he said he couldn’t do anything with Chaplin. Sennett called Chaplin to him.

The Keystone people say that the hardest “calldown” anybody ever got at the Keystone was that handed to Charlie Chaplin by Sennett because he refused to obey the director.

Chaplin took the boss’s breezy remarks as toasts to the President are drunk — standing and in silence. But he went right on acting in his own way. Finally, Lerhmann passed him on to another director, who had an equally bad time with him.

The Keystone people came to the conclusion that they had picked up a fine lemon in Chaplin. Personally, he was very popular, but it was generally agreed that he would never make good as a picture actor.

Finally, Mack Sennett took a hand at directing Chaplin himself. They were then putting on a piece called “Mabel’s Strange Predicament.” Chaplin had a small part where he did some funny business in the lobby of a hotel. Mack Sennett decided to see just what this Englishman would do if they let him have his own way. He turned the misfit loose and let him be as funny as he liked.

Then and there Charlie Chaplin suddenly “happened.”

Mack Sennett saw in a flash that some big stuff was going over, and from that minute, Chaplin became a real star.

Sennett, during the next few pictures, put in Chaplin to do little comedy bits that called for the same kind of stuff he showed in the lobby of the hotel. Chaplin was always funny in these bits, but Sennett saw that, to be entirely successful he must have a company of his own. The other actors’ work was out of tune with the Chaplin method.

Sennett was quick to see that almost immeasurable things could be gotten out of Chaplin, but he also saw that the Chaplin pictures must, in the future, be built with Chaplin as the foundation. The whole comedy must be adjusted to his tempo, and even the scenario would have to be different from the kind of scenario ordinarily used bv the Keystone people. It must be slower and more subtle.

The end of it was that Chaplin was finally allowed to direct his own scenarios. No American picture director understood his peculiar style of comedy well enough to work out the stuff. In another chapter I will tell about Chaplin’s work and his methods as a director.

Chaplin’s first big hit as a director of his own work was “Dough and Dynamite.” This was started as a part of the scenario afterward known as the “Pangs of Love.”

In his rather aimless way of directing without any scenario, Chaplin and Mr. Conklin began working up a play in which both he and Conklin were in love with the landlady of a boarding house and stuck hatpins into each other through a curtain to interrupt one another’s courtship. They decided that they both ought to be workmen of some kind and decided upon being bakers.

As part of the play, they worked up a scene in a bake shop. This turned out to be so funny that they finally changed the whole idea and made two different scenarios.

As a director-actor at the Keystone, Chaplin had the reputation of being the most generous star in the movie business. Every comedian was allowed to grab all the laughs he could get. Chaplin always insisted on having them do the comedy stuff in his way, but he always built up their parts for them without regard for the fact that his own might suffer.

His work began making a tremendous impression. Everyone began talking about the new funny man. People who never went to the movies before were drawn by the accounts of the new comedian.

MORE: See some of the best Chaplin quotes here

Naturally, the other movie companies took notice, and Chaplin got several big offers. One from the Essanay was so big that he did not feel justified in refusing. When his contract expired with the Keystone, he changed companies. He went with the understanding that he was to have full swing in his work: direct all his own scenarios and do pretty much as he pleased.

Essanay work was done in Chicago. His first Essanay film was after that he put on “His Night Out.”

Chaplin then insisted on moving back to California. The picture conditions didn’t suit him in the Middle West. On returning to the Coast, he went to the Essanay studio at Niles.

In a separate chapter, there will be an account of his adventures at this rural studio. He produced “The Tramp” at Niles. This is regarded in some ways as the most remarkable step forward that has ever been made in moving picture comedy.

Returning from Niles, Chaplin went to the Essanay studio in an old mansion near the business district of Los Angeles. Here he has been working ever since. At least this is his base of operations. From this house, he works out to the beaches and various “locations” near Los Angeles.

By this time a perfect storm of fame had struck Chaplin. To tell the truth, it seemed to scare more than anything else. He used to say to his intimate friends, “I can’t understand all this stuff. I am just a little nickel comedian trying to make people laugh. They act as though I were the King of England.” Chaplin even to this day is much alarmed over being so famous. He says his reputation can’t last.

But he began to suffer the penalties of the great. He was asked to speak at banquets, to lead parades, to referee prizefights. When the baseball season opened. it was announced that Chaplin would throw the first ball.

All of this stuff worried Chaplin a good deal at first. He said he picked up the paper every morning with apprehension to see what foolish thing he was due for that day.

‘He found that it didn’t worry the promoters of these various events at all, however. They announced that he would referee at prize fights, and when he did not appear, they simply dressed up a boy in Chaplin’s style in clothes and he appeared, serene in the belief that nobody would know the difference. There is a boy in Los Angeles who makes a good living by dressing up like Charlie Chaplin and parading up and down in front of the theaters where the Chaplin films are being shown.

Charlie was pursued like a wounded hare by all kinds of people with all kinds of business propositions. If half the life insurance agents who were on his trail could be gathered into an army, there wouldn’t be any danger of a war with Germany. Real estate agents wanted him to buy houses. Inventors wanted him to take stock in their discoveries.

About a million people wrote him letters. Many of them were mash letters. One young lady in Chicago undertook the job of censoring all his work. Every day of her life she wrote Chaplin a letter, commenting critically on some of his latest films. Sometimes she complimented them; sometimes she roasted them un-tenderly.

Charles Chaplin’s business sense

Chaplin about as much a business system as a chicken. When his friends came to see him at his hotel, they found him sitting helplessly behind a pile of letters. Finally some of his friends prevailed on him to hire a secretary. Wherefore a severe young man with glasses now opens Charlie’s mash letters.

One sort of pest scared Chaplin to death. This was the auto agent. They wanted him to buy their cars: to be photographed in their cars and to write endorsements of their cars. But Charlie was adamant. He wouldn’t listen to any of them. He told them he had an aversion to cars on principle, and when he retired he was going to have an old white horse and buggy and a ranch.

The truth is, Charlie had once been bitten by the automobile bug. While he was with the Keystone, Chaplin fell for the blandishments of an auto agent, and came out one day nervously driving a runabout. He had some weird experiences with that car. He never could learn how the thing worked. He knew how it started but he never could remember — at least in times of emergency — what you did when you wanted the thing to stop.

One day while he was parading the boulevards with his vehicle, Chaplin came to the intersection of two crowded streets. The traffic cop majestically gave the signal for the car to stop. Charlie reached for the thingamajig and pulled the wrong lever. The car bounded blithely forward. The cop waved his club and that was all he did before the auto struck him amidships and mopped up the floor with him.

They picked up the fragments of the officer of the law. They also picked up Chaplin and took him to the police station, where they advised him to learn how to manage his car and charged him $75 for the advice.

Another time, Charlie was driving in through the big front gate at the Keystone and got too near one of the posts. He had been used to sailing small boats. When a small boat gets too near the wharf the thing to do is to drop the tiller and fend off by pushing against the wharf. Charlie thought this ought to apply equally well to a car. So when he saw he was going to bump the gate, he dropped the steering wheel and tried to push off from the post. The results were sensational and startling.

Another time, Charlie’s car was on the side of a hill. It started to roll down, and Chaplin tried to stop it by grabbing the hind wheels. Results equally startling and sensational.

When Chaplin discovered that new tires for his motor cost $75 each, his soul called “Enough,” and he returned to street cars. Since then he has been a mighty poor prospect for an auto agent.

Some of the attention that came to Chaplin with his fame was enjoyable. Thousands of people speak to Chaplin on the street without knowing him. They are always answered courteously.

Not long ago, I saw two old people stop and stare and begin to nudge each other in great excitement. Charlie Chaplin was coming down the street. When he came near, the old man gathered his courage and said, “Hello, Charlie Chaplin.” Chaplin lifted his hat in the odd way that he does on the screen and said, “Howdydo” and passed on. The old people were tickled to death.

The one thing that got the comedian’s goat was speaking at banquets. Just once it is recorded that he was prevailed upon and human agony can have no fuller expression than this quivering actor waiting to speak his piece.

The culmination of his fame came probably with the offer of a New York theatrical man to give him $25,000 for an engagement of two weeks — an offer which the Essanay company is supposed to have met to induce him to stay away from the stage.