How Rose Wilder Lane turned a weaving essay into a declaration of freedom

That’s because Rose Wilder Lane (1886 -1968) was a remarkable woman in her own right, particularly when it came to choosing the perfect words. She worked for many years as a journalist, travel writer, novelist, political theorist… and, as evidenced by the excerpted piece below, an essayist.

Unfortunately, Rose died before ever seeing the success of the iconic — and quintessentially American — TV show Little House on the Prairie, based (somewhat loosely) on the book series. We like to imagine she would have loved to see Melissa Gilbert playing the ever-curious Laura, and that she would have been charmed by Michael Landon, whose portrayal of her grandfather, Pa Ingalls, warms hearts even decades later.

Throughout her wide-ranging writing career, Lane explored everything from world politics to family legacies. She had a strong voice and a sharp eye for connecting everyday life with broader ideas. Her work often reflected her deep belief in individual responsibility and personal freedom, and she returned to those themes again and again. In 1962, she applied that perspective to a topic rooted in the home: weaving.

Her essay, published in Woman’s Day, explored the cultural and historical role of weaving in American life. She didn’t treat it as decoration or nostalgia. Instead, she described it as one of the first ways early American women expressed independence.

As she told it, spinning wool, dyeing yarn, and weaving cloth were daily acts with serious meaning. When British trade rules forbade colonial households from weaving their own textiles, many women kept on weaving anyway. They used tools built by hand, with thread dyed from plants they grew themselves, to make clothes, bedding, and other essentials. Lane described these moments as powerful and deliberate, with looms thumping out a rhythm that echoed the demand for liberty.

She contrasted this spirit with weaving traditions in other parts of the world, where patterns and methods were often prescribed by guilds or governments. In America, she said, women created their own patterns and chose their own colors.

Cloth from the colonies carried personal choices and regional traditions, not instructions from a king. Her example of a tribal loom she saw in rural Russia showed how far human effort could go with simple tools. But it also reinforced her view that the American approach to craft — guided by need, ability, and free will — had something special to offer.

To show how Rose Wilder Lane brought all this together in one article, we’ve included her original piece below, along with images that capture the texture of her words. It’s a fascinating look at how a practical skill helped shape American ideas, and how Lane never overlooked the meaning behind everyday work.

American needlework: Weaving

by Rose Wilder Lane in Woman’s Day (March 1962)

Weaving, the crisscrossing of strands together to make a fabric, is the only art craft to engage and delight all of one’s mind and muscles together. The rhythm is in your blood, a warmth spreads to the tips of fingers and toes. A radiance seems to encompass everything.

Everyone knows that weaving is crisscrossing strands together to make a fabric, but only weavers think about it. If you’re simply taking it for granted as so many of us do nowadays, just try to imagine what would happen if everything woven, suddenly vanished. We would he naked; there would be no clothes, no bedding, no carpets, curtains, not so much as a towel; mills, factories, cars would stop running; in warehouses and cargo ships everything sacked or baled would flow into heaps; cloth-bound books would be loose pages, typewriters would have no ribbons. And that’s hardly the beginning of it.

Weaving is a primary essential to civilization. It was one of our savage ancestors’ first efforts to climb out of savagery; its history is inseparable from the history of the ages-long struggle toward a truly civilized human world. So in that continuing effort it has a special meaning now; for it was women in America, quietly weaving, who began the world revolution for individual freedom.

King George the Third was a good ruler, sincere and conscientious. He worked hard and unselfishly to do his duty of managing his subjects for the common good. When he decided to permit them to weave in Eng!and and forbid them in America, he was acting as good rulers always had acted. When King Louis XIV decided to protect his vintners in France and ordered his subjects in America to stop making wines, they stopped.

But French kings had selected their American colonists carefully, given them food and seeds and hoes, and set over them commanders who had always told them what to do and taken care of them. Refugees had made the English colonies, with no help nor government from England. They starved until, in utmost desperation, they learned that God gives every person, with life, the responsibility for it. With this knowledge they had lived, they had prospered for nearly two centuries. Now their king asserted his own control of their lives, his responsibility for them: He would permit them to raise flax and wool to ship to England, but not to weave at home.

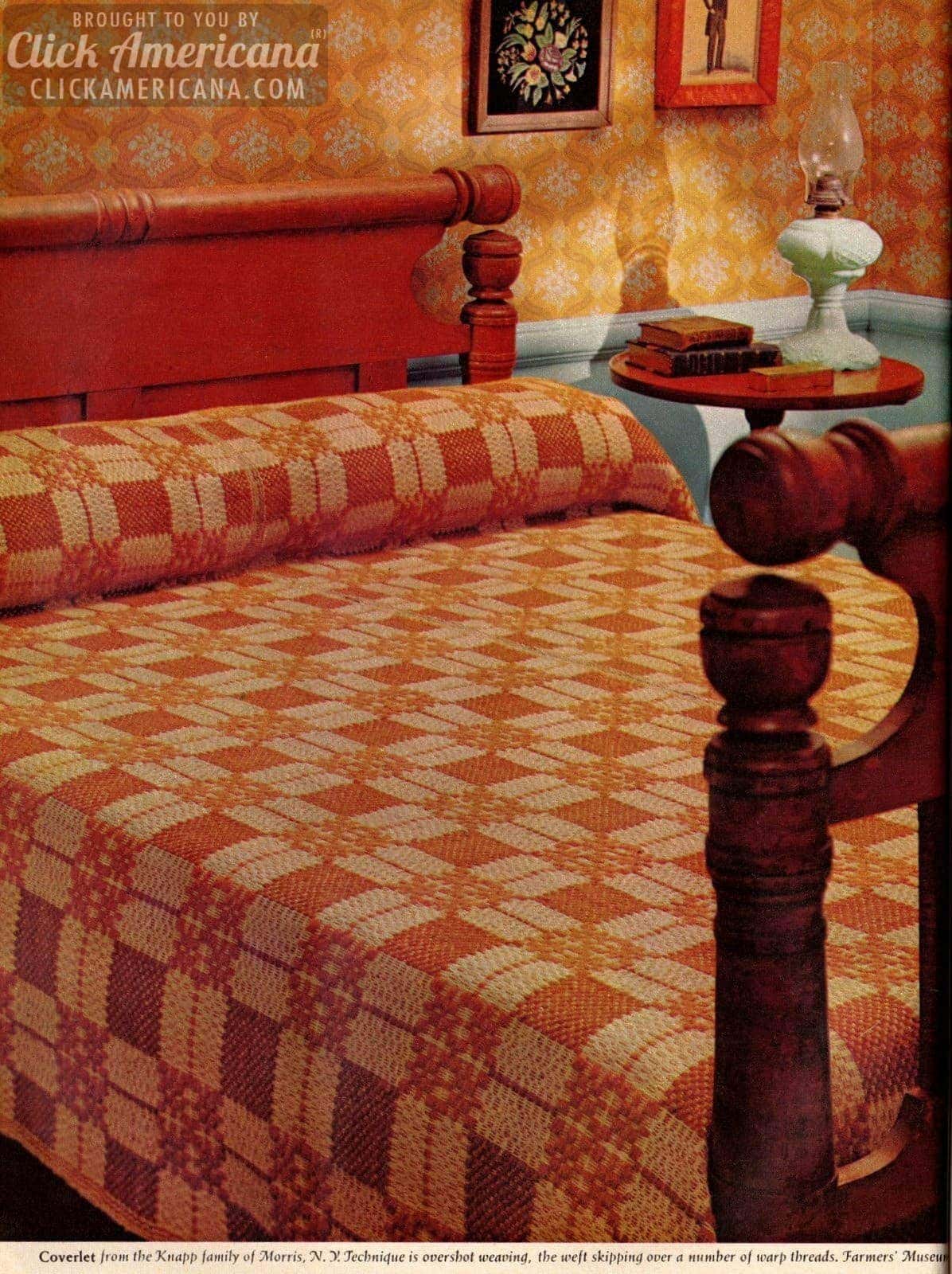

A housewife had made the flaxen thread, from seed to hank. She had made the woolen yarn in a year of tending sheep, washing and carding and spinning the oily fleeces. Her fingernails were blue from the indigo vat, and she had probably raised the indigo. Her husband had made for her the spinning wheel and the loom, hewed and whittled and smoothed and pegged together of wood from the living tree. These things are mine, she said.

The king said that she must not use them? When the children needed clothing, the new bed lacked bedding?

She warped the thread and beamed the warp and threaded it through the heddles and the reed; she wound the weft on the worn-smooth shuttle. She sat down, her feet on the treadles. Then in the village street and by the cabin in the clearing, men heard the thump-thud of the busy looms, drumbeating the battle cry that they would shout from Bunker Hill to Yorktown: “Liberty and property!”

Already these women were weaving the American patterns that we cherish now.

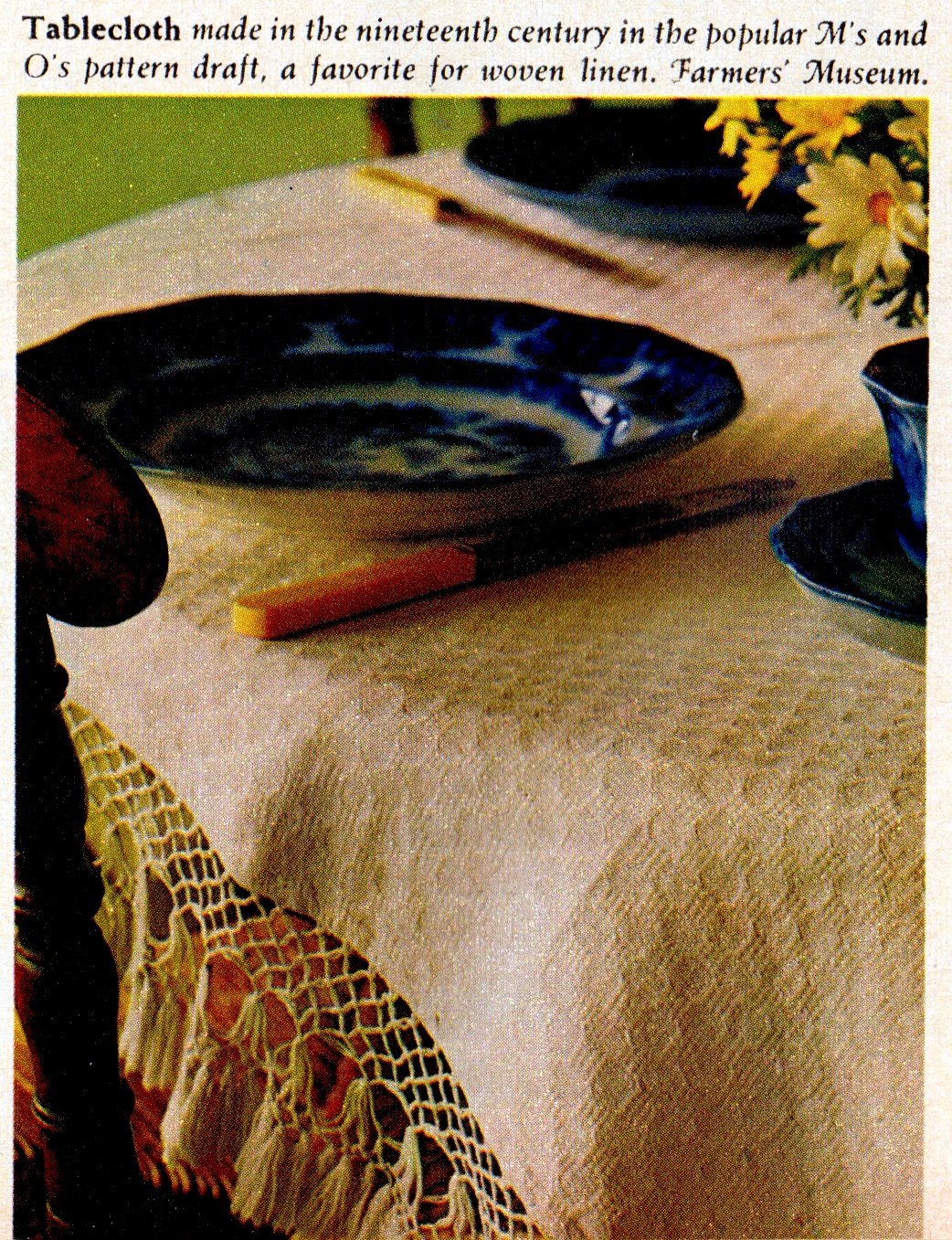

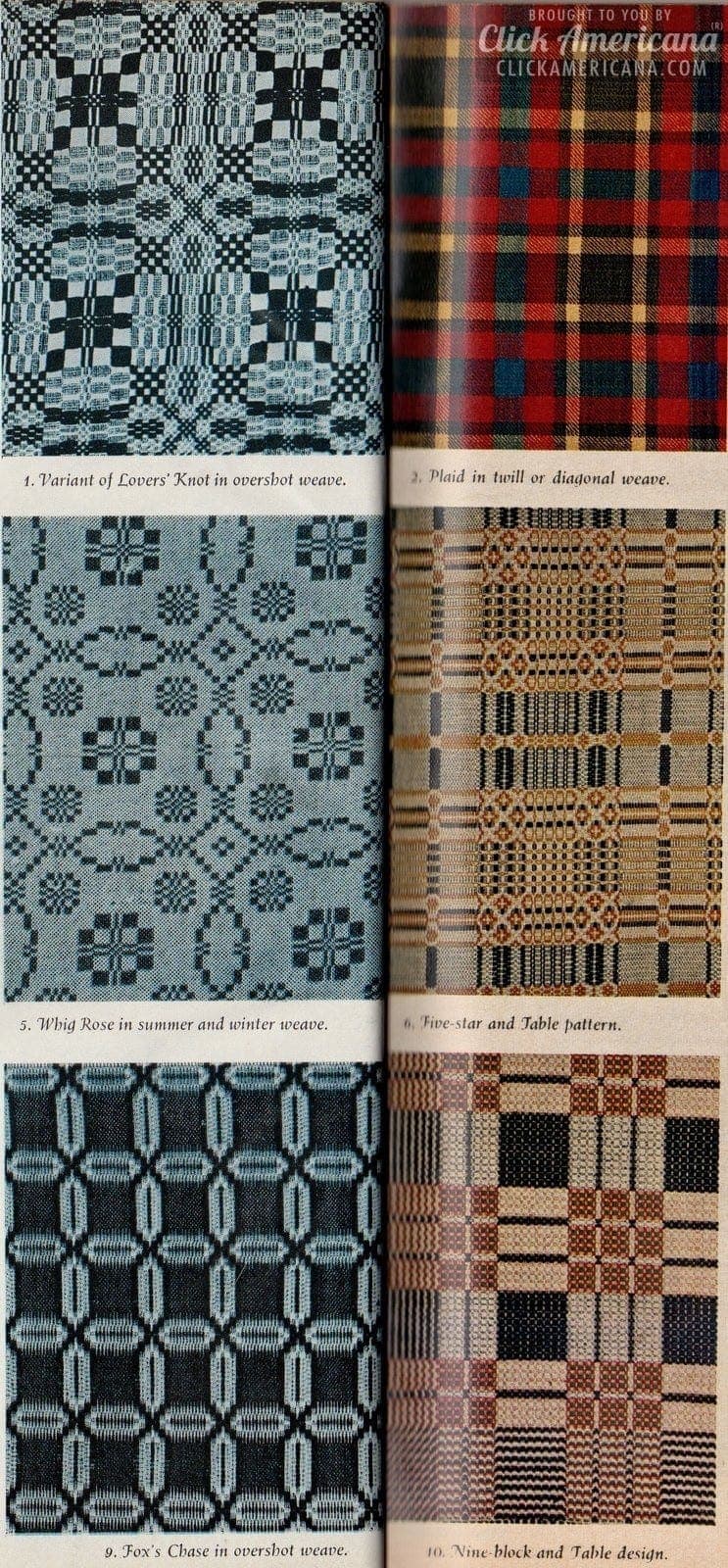

In Europe’s chartered and privileged guild monopolies, the workers and their masters were weaving the patterns prescribed, large patterns of blended colors, tapestries for castle walls, so many threads of warp to the inch and so many threads of woof, by order of the king. In America, the independent women each wove her own pattern. They set the small motifs on creamy white, on indigo blue, on brown from the walnut hull or yellow from the peach leaf. Each motif stood alone and clear and firm, and all together the colors sang from the cloth.

There was nothing new in the loom itself. Thousands of years of thinking, trying, failing, thinking and trying again, had made that eighteenth-century loom. In 1922, I saw a rather early success in that long effort. It was the pride of one of the hundreds of primitive tribes in Russia, with their hundreds of languages, religions and stages of culture. This was a tribe of barbarians. The great-grandfathers had been wandering savages; the grandfathers had settled in a village on the empty Georgian plain. Now the tribesmen sowed and reaped barley and grazed goats on the land that nobody owned, and the tribe had a loom. Eagerly they led me to see it.

The village was a haphazard cluster of round huts made of boughs, the butts thrust into the ground, the tops tied together, and all inter-woven with reeds. A hide hung over the doorway. We had to stoop low, almost to crawl into the airy room where speckles of sunshine came through the walls, and the earth was trodden almost bare of grass. There were heaps of barley straw, evidently beds. And in the center stood the loom.

It was, roughly, a wheel made of peeled wands, as nearly round as their stubbornness permitted. About a yard in diameter, it had a rim, perhaps two feet wide, of sticks tied crosswise. On these, around the rim, a continuous length of yarn had been wound as evenly as possible; this was the warp. A few inches of cloth were already woven and a gay young woman proudly showed me how to weave.

Swiftly her fingers pulled and pushed an end of yarn under and over the threads of warp, from left to right. With care she urged a yard or so of yarn through; then she clawed it down as close to the web as she could get it. Back, over and under the threads of warp, she pushed and pulled the yarn, and again clawed it down.

With gestures, the others explained that when the weaving was done all around the wheel they would break the warp, tie its ends together and have a piece of cloth!

It would be coarsely woven of the lumpy goats’-wool yarn spun with fingers twirling a dangling stone. But look at it with the eyes of primitive man, naked on this planet with only mind and hands to use, and you see what an achievement it was.