That morning in Dallas began with crowds and handshakes at Love Field. By 12:30 p.m., shots rang out in Dealey Plaza as the presidential motorcade passed the Texas School Book Depository. President John F. Kennedy was rushed to Parkland Hospital, where he was pronounced dead shortly after 1 p.m. Texas Gov. John Connally was seriously wounded. Within hours, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson took the oath of office aboard Air Force One before returning to Washington. The speed of events left little time for reflection as editors worked to confirm facts and meet deadlines.

Early reports focused on the arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald, a former Marine who had recently worked at the depository building. The Dallas Morning News described the location of the shots and the recovery of a rifle from the sixth floor. In those first hours, details were incomplete and often conflicting. Headlines reflected both urgency and uncertainty, capturing how information moved in 1963 — through wire services, police briefings and eyewitness accounts.

National magazines soon followed with longer examinations. LIFE devoted extensive coverage to photographs from the scene, including images of the motorcade route and the now-famous frames from Abraham Zapruder’s home movie camera. By 1966, debates about the findings of the Warren Commission had entered public discussion, with Gov. Connally offering his own interpretation of the sequence of shots as seen on film. The printed page became the primary forum for Americans trying to understand what had happened.

VIDEO | Walter Cronkite reports on John F. Kennedy’s assassination on Nov. 22, 1963

Coverage also turned to the personal dimension of loss. Accounts described First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy remaining beside her husband in Dallas and accompanying his casket back to Washington. Writers reflected on Kennedy’s youth, his presidency and the sense of possibility many associated with his administration. The tone ranged from clinical reconstruction to open grief, revealing how journalism attempted to balance fact and feeling.

Below, we’ve gathered original newspaper reports, magazine spreads and photographs published in the days and years after the assassination of President Kennedy, showing how Americans first learned the news, how the story was investigated and how the memory of that day was shaped in print.

The assassination of President Kennedy

From LIFE – November 29, 1963

Now in the sunny freshness of a Texas morning, with roses in her arms and a luminous smile on her lips, Jacqueline Kennedy still had one hour to share the buoyant surge of life with the man at her side.

It was a wonderful hour. Vibrant with confidence, crinkle-eyed with an all-embracing smile, John F Kennedy swept his wife with him into the exuberance of the throng at Dallas’ Love Field.

This was an act in which Jack Kennedy was superbly human. Responding to the warmth his own genuine warmth evoked in others, he met his welcomers joyously, hand to hand and heart to heart. For him this was all fun as well as politics.

For his shy wife, surmounting the grief of her infant son’s recent death, this mingling demanded a grace and gallantry she soon would need again. Then the cavalcade, fragrantly laden with roses for everyone, started into town. Eight miles on the way, in a sixth-floor window, the assassin waited. All the roses, like those here abandoned in Vice President Johnson’s car, were left to wilt.

They would be long-faded before a stunned nation would fully comprehend its sorrow.

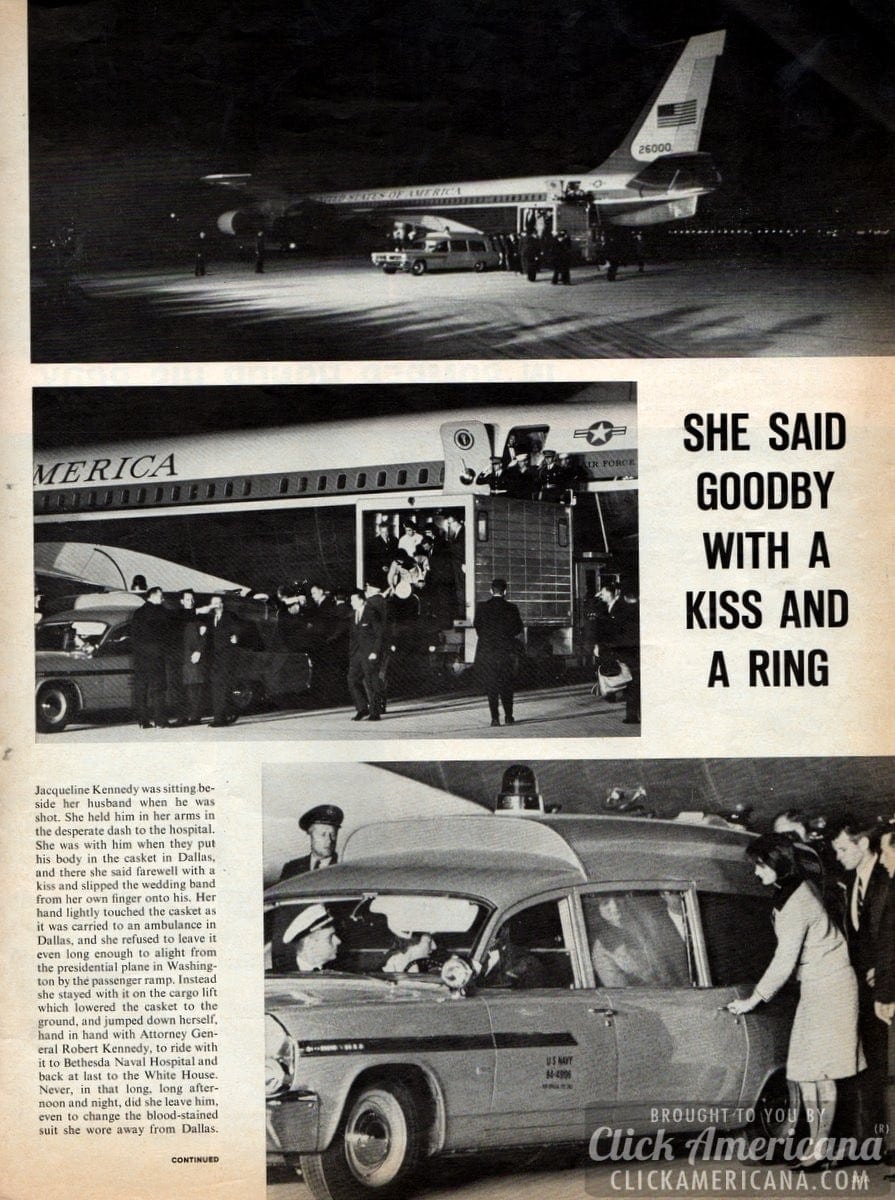

She said goodbye with a kiss and a ring

Jacqueline Kennedy was sitting beside her husband when he was shot. She held him in her arms in the desperate dash to the hospital. She was with him when they put his body in the casket in Dallas, and there she said farewell with a kiss and slipped the wedding band from her own finger onto his.

Her hand lightly touched the casket as it was carried to an ambulance in Dallas, and she refused to leave it even long enough to alight from the presidential plane in Washington by the passenger ramp.

Instead, she stayed with it on the cargo lift which lowered the casket to the ground, and jumped down herself, hand in hand with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to ride with it to Bethesda Naval Hospital and back at last to the White House.

Never, in that long, long afternoon and night, did she leave him, even to change the blood-stained suit she wore away from Dallas.

Kennedy slain on Dallas street: Pro-Communist charged in act

The Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas) November 23, 1963

A sniper shot and killed President John F Kennedy on the streets of Dallas Friday. A 24-year-old pro-Communist who once tried to defect to Russia was charged with the murder shortly before midnight.

Kennedy was shot about 12:20 pm Friday at the foot of Elm Street as the Presidential car entered the approach to the Triple Underpass. The President died in a sixth-floor surgery room at Parkland Hospital about 1 pm, though doctors say there was no chance for him to live after he reached the hospital.

Within two hours, Vice President Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as the nation’s 36th President inside the presidential plane before departing for Washington.

The gunman also serously wounded Texas Governor John Connally, who was riding with the President.

Four hours in surgery

Connally spent four hours on an operating table, but his condition was reported as “quite satisfactory” at midnight.

The assassin, firing from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository Building near the Triple Underpass, sent a Mauser 6.5 rifle bullet smashing into the President’s head.

An hour after the President died, police hauled the 24-year-old suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald, out of an Oak Cliff movie house.

He had worked for a short time at the depository, and police had encountered him while searching the building shortly after the assassination. They turned him loose when he was identified as an employee but put out a pickup order on him when he failed to report for a work roll call.

He also was accused of killing a Dallas policeman, J D Tippit, whose body was found during the vast manhunt for the President’s assassin.

Oswald, who has an extensive pro-Communist background, four years ago renounced his American citizenship in Russia and tried to become a Russian citizen. Later, he returned to this country.

Friendly crowd cheered Kennedy

Shockingly, the President was shot after driving the length of Main Street through a crowd termed the largest and friendliest of his 2-day Texas visit. It was a good-natured crowd that surged out from the curbs almost against the swiftly moving presidential car. The protective bubble had been removed from the official convertible.

Mrs Connally, who occupied one of the two jump seats in the car, turned to the President a few moments before and remarked, “You can’t say Dallas wasn’t friendly to you.”

Death found him from this window

From this grimy warehouse window ledge of the Texas School Book Depository, the assassin shot President Kennedy.

Stacked book cartons, one of which still lies in right foreground, afforded him makeshift privacy, but he perilously risked exposure by any passerby. It is not yet known how long he waited, but police found an empty soft drink bottle, a crushed cigarette package and gnawed remnants of fried chicken in a greasy paper bag.

This photograph was made a day later to re-create the scene. The President’s car had just turned left off Houston Street (where white ornamental fence curves at lower left) and onto Elm Street which funnels into the triple underpass. Slowed by cornering, the car was traveling only about 15 mph when it reached the point in the center lane indicated by an arrow. At that moment, two loud, sharp reports were heard and then another.

Measured as sniper’s work, the shooting was remarkably effective. The target was moving. 75 yards from the muzzle and about 60 feet lower than the assassin. And both the President and Governor John Connally were hit within seconds.

Under the window police found three spent cartridges and one unused. Then, hidden between two stacks of books, they found the weapon, a beat-up sawed-off .30- caliber rifle of Italian make fitted with a four-power telescopic sight.

President Kennedy’s assassination: Zapruder footage (1966)

Amid controversy over the Warren Report, Governor Connally examines for LIFE the Kennedy assassination film frame-by-frame.

Did Oswald act alone? A matter of reasonable doubt

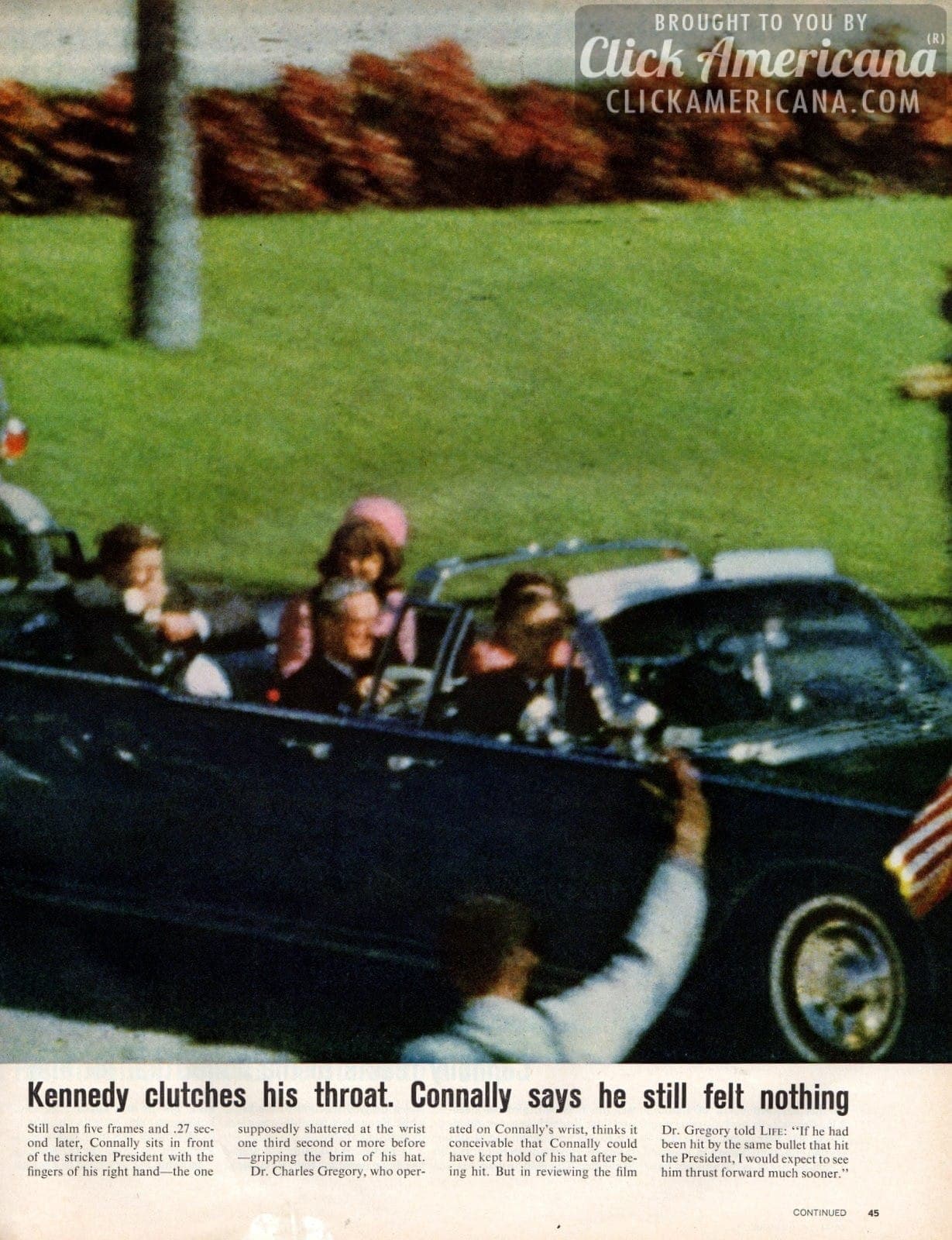

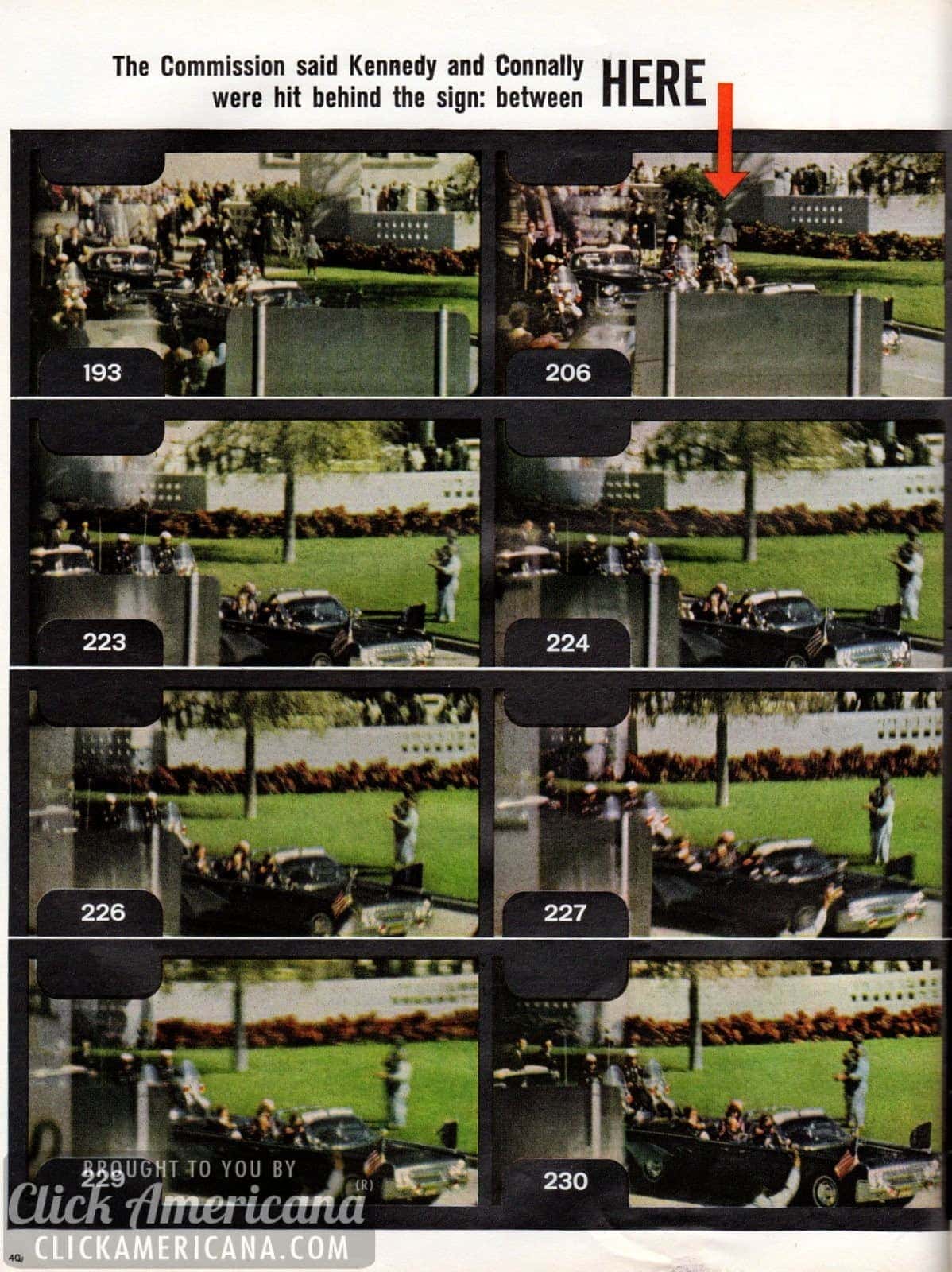

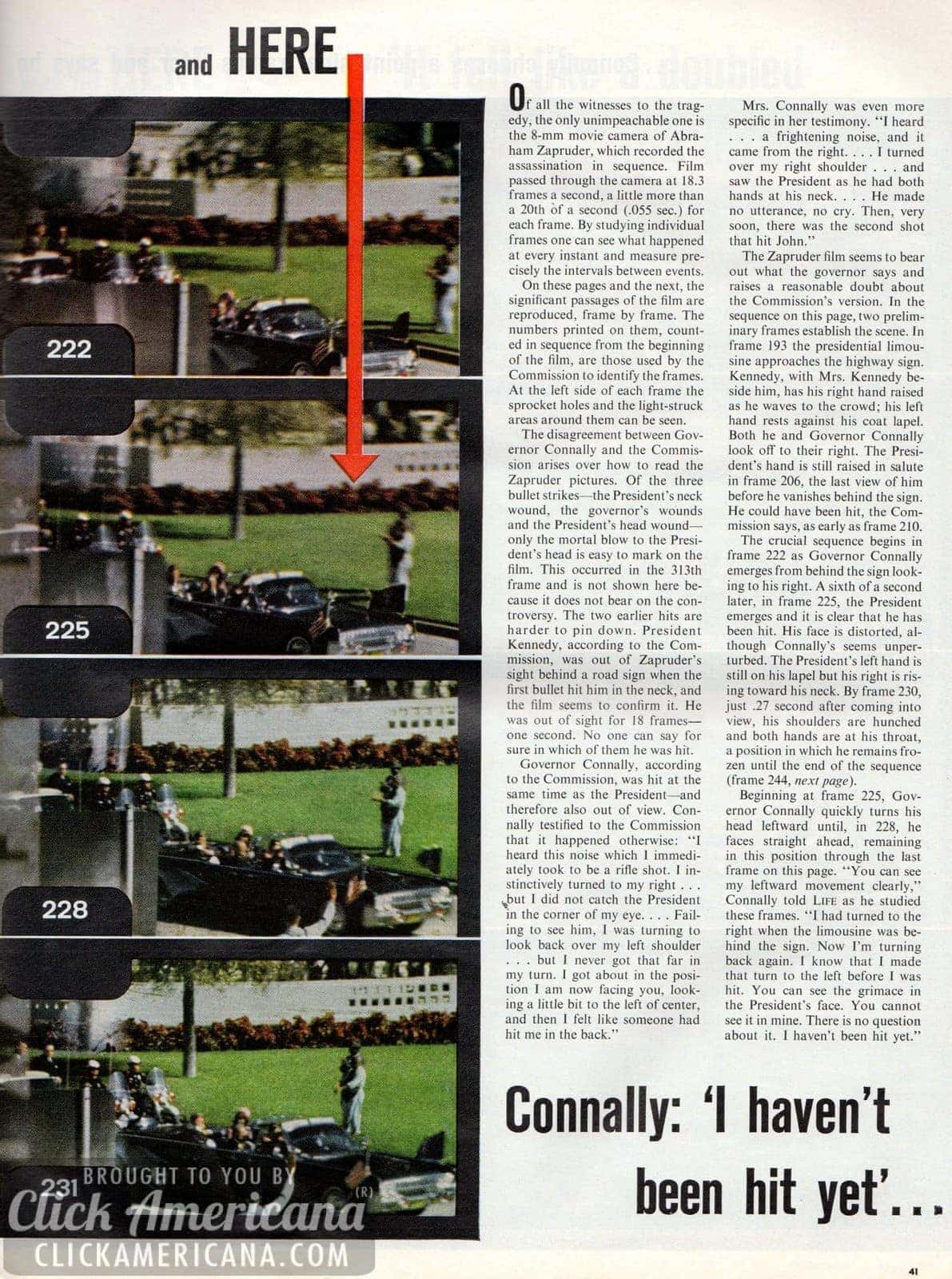

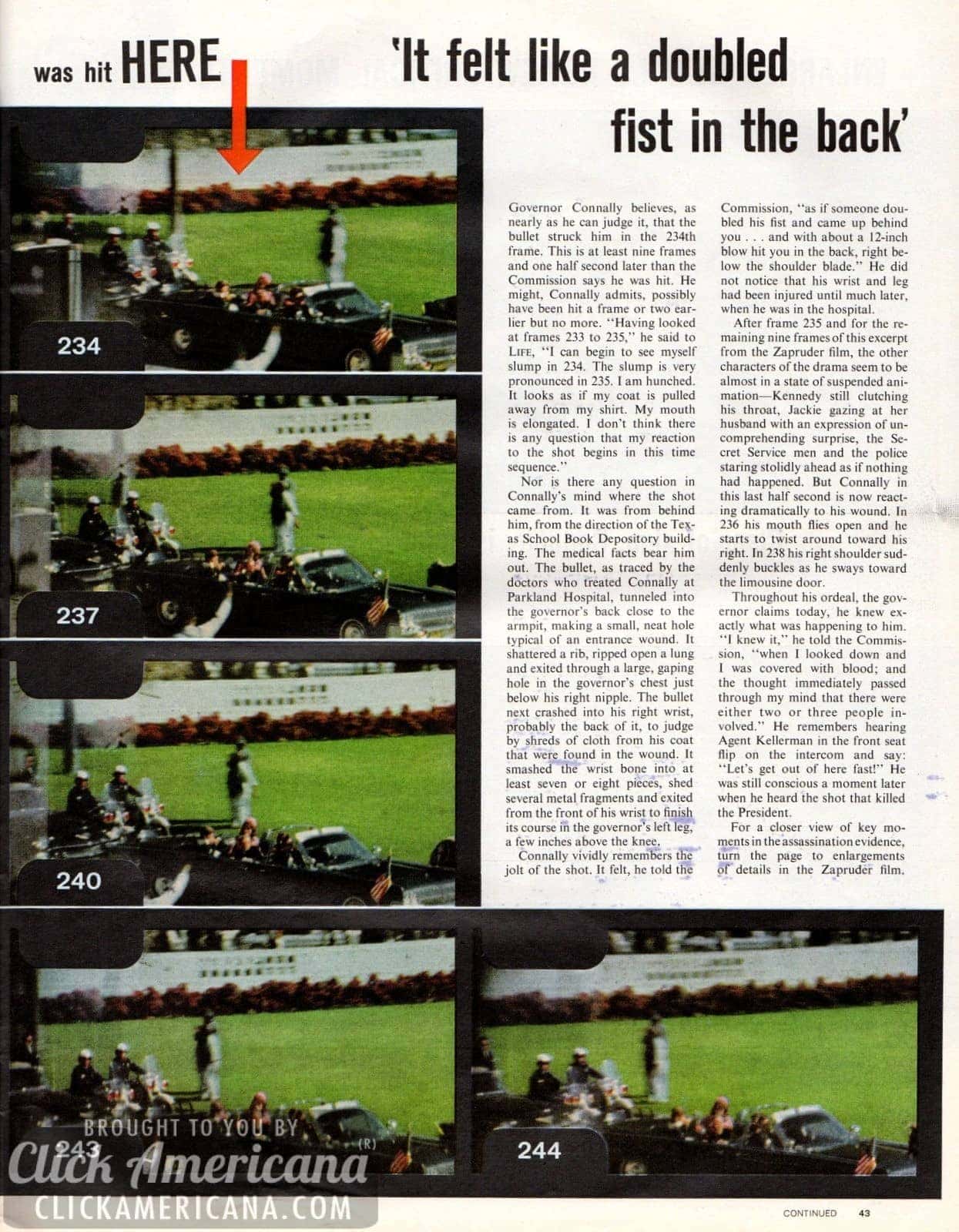

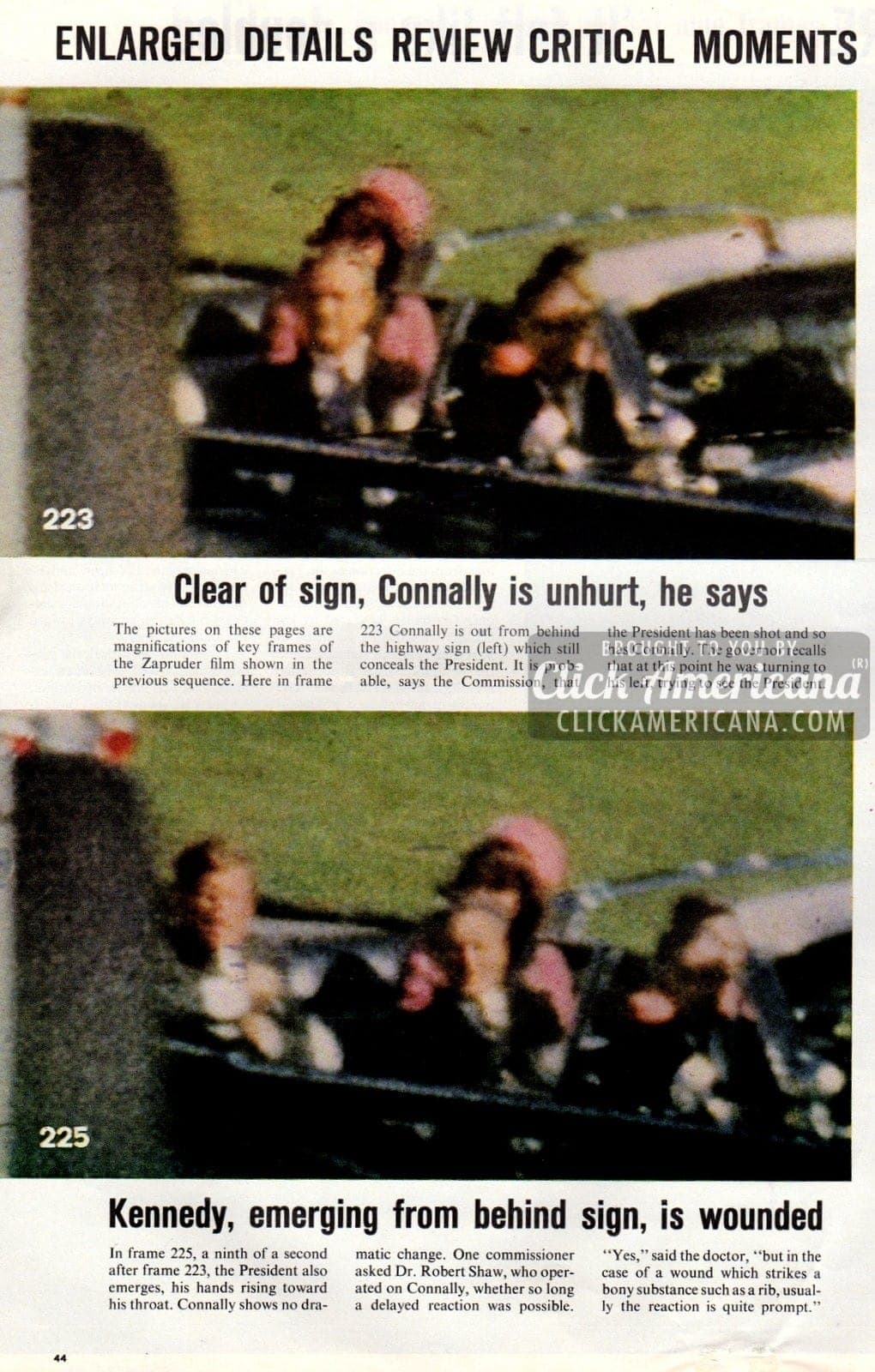

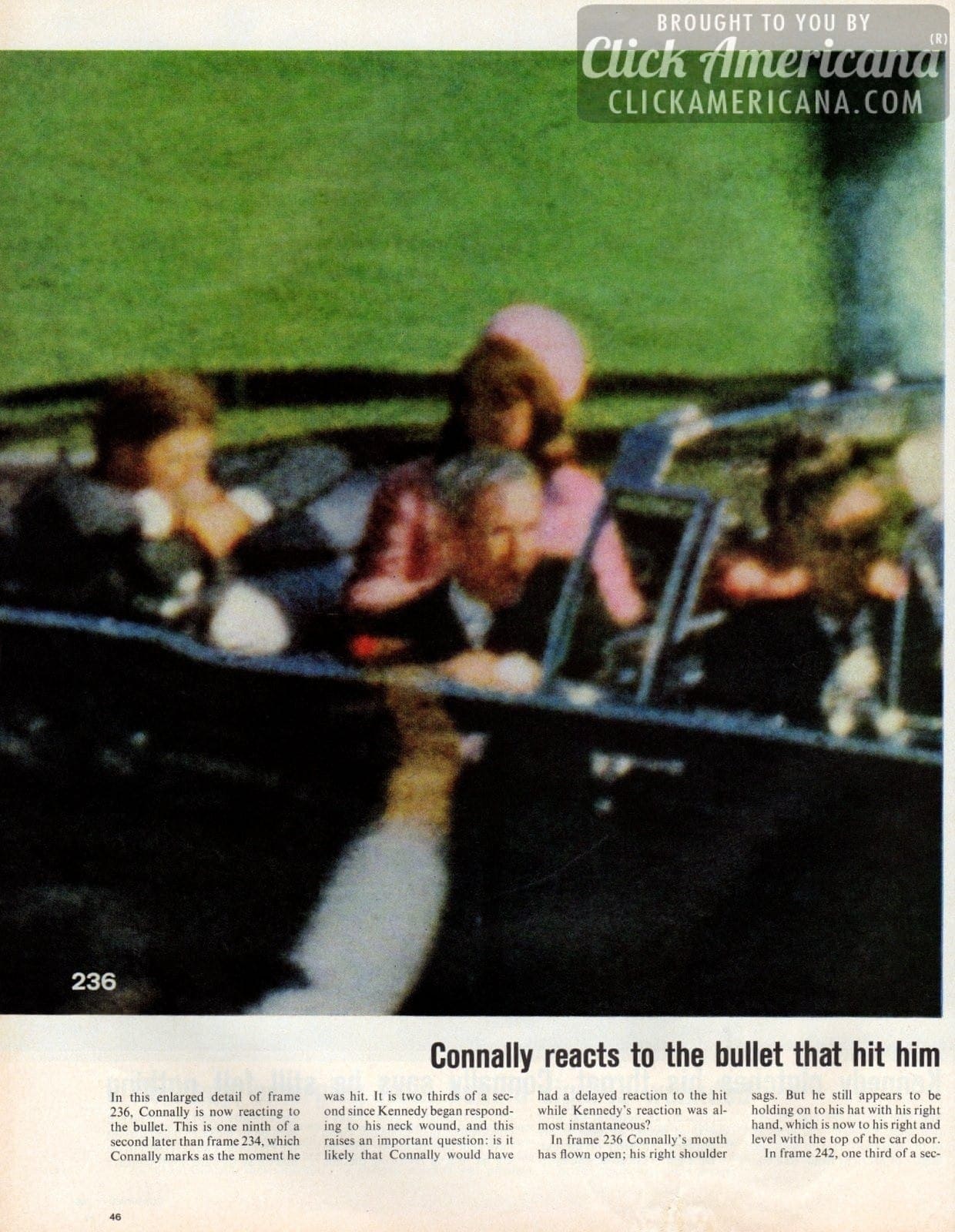

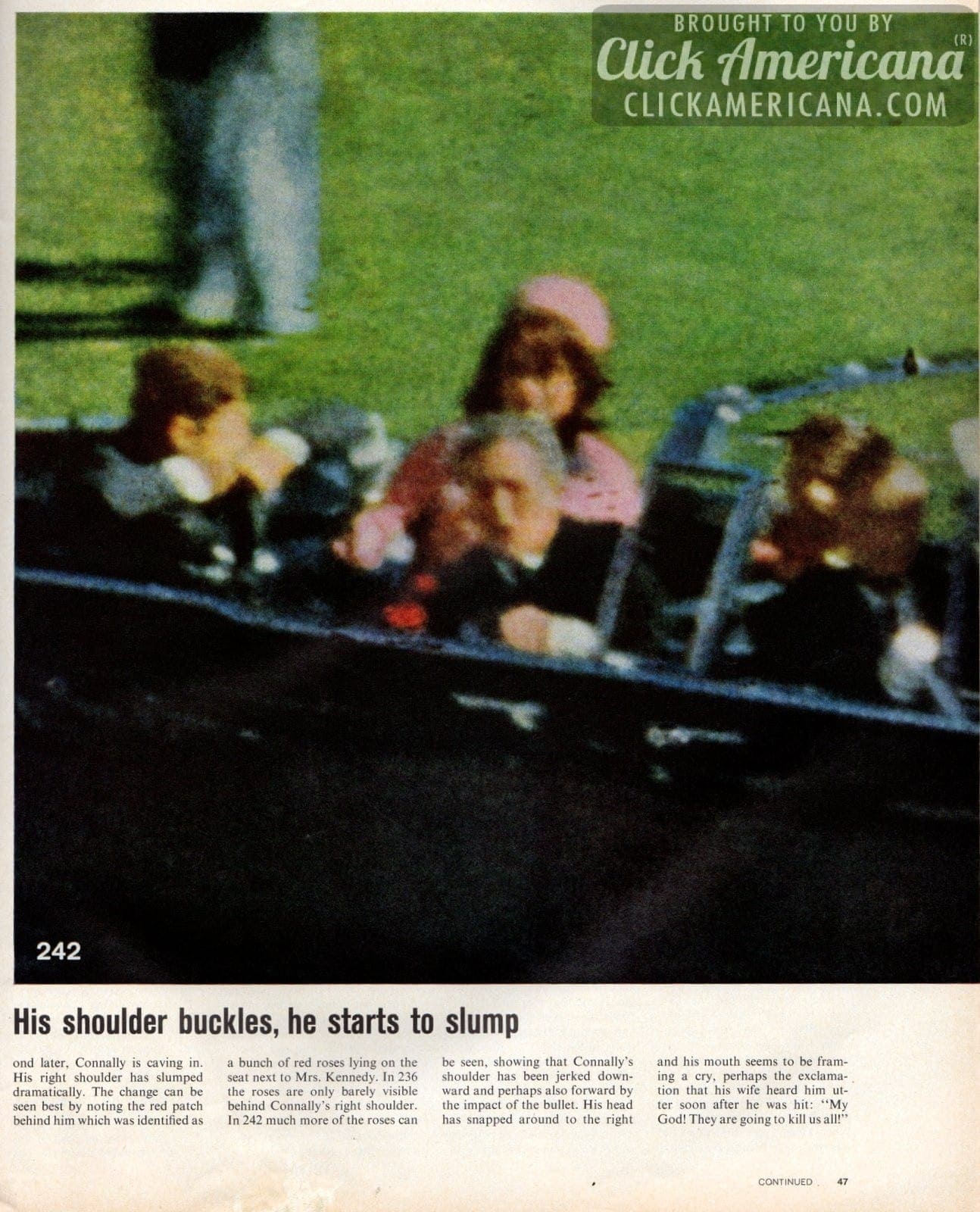

Of all the witnesses to the tragedy, the only unimpeachable one is the 8-mm movie camera of Abraham Zapruder, which recorded the assassination in sequence.

Film passed through the camera at 18.3 frames a second, a little more than a 20th of a second (.055 sec.) for each frame. By studying individual frames, one can see what happened at every instant and measure precisely the intervals between events.

On these pages and the next, the significant passages of the film are reproduced, frame by frame.

The numbers printed on them, counted in sequence from the beginning of the film, are those used by the Commission to identify the frames. At the left side of each frame the sprocket holes and the light-struck areas around them can be seen. The disagreement between Governor Connally and the Commission arises over how to read the Zapruder pictures.

Of the three bullet strikes — the President’s neck wound, the governor’s wounds and the President’s head wound — only the mortal blow to the President’s head is easy to mark on the film. This occurred in the 313th frame and is not shown here because it does not bear on the controversy. The two earlier hits are harder to pin down.

President Kennedy, according to the Commission, was out of Zapruder’s sight behind a road sign when the first bullet hit him in the neck, and the film seems to confirm it. He was out of sight for 18 frames — one second. No one can say for sure in which of them he was hit. Governor Connally, according to the Commission, was hit at the same time as the President — and therefore also out of view.

Connally testified to the Commission that it happened otherwise: “I heard this noise which I immediately took to be a rifle shot. I instinctively turned to my right… but I did not catch the President in the corner of my eye… Failing to see him, I was turning to look back over my left shoulder… but I never got that far in my turn. I got about in the position I am now facing you, looking a little bit to the left of center, and then I felt like someone had hit me in the back.”

Mrs Connally was even more specific in her testimony. “I heard… a frightening noise, and it came from the right… I turned over my right shoulder… and saw the President as he had both hands at his neck… He made no utterance, no cry. Then, very soon, there was the second shot that hit John.”

The Zapruder film seems to bear out what the governor says and raises a reasonable doubt about the Commission’s version. In the sequence on this page, two preliminary frames establish the scene. In frame 193, the presidential limousine approaches the highway sign.

Kennedy, with Mrs Kennedy beside him, has his right hand raised as he waves to the crowd; his left hand rests against his coat lapel. Both he and Governor Connally look off to their right. The President’s hand is still raised in salute in frame 206, the last view of him before he vanishes behind the sign. He could have been hit, the Commission says, as early as frame 210.

The crucial sequence begins in frame 222 as Governor Connally emerges from behind the sign looking to his right. A sixth of a second later, in frame 225, the President emerges and it is clear that he has been hit. His face is distorted, although Connally’s seems unperturbed. The President’s left hand is still on his lapel, but his right is rising toward his neck.

By frame 230, just .27 second after coming into view, his shoulders are hunched and both hands are at his throat, a position in which he remains frozen until the end of the sequence (frame 244).

Beginning at frame 225, Governor Connally quickly turns his head leftward until, in 228, he faces straight ahead, remaining in this position through the last frame on this page.

“You can see my leftward movement clearly,” Connally told LIFE as he studied these frames. “I had turned to the right when the limousine was behind the sign. Now I’m turning back again. I know that I made that turn to the left before I was hit. You can see the grimace in the President’s face. You cannot see it in mine. There is no question about it. I haven’t been hit yet.”

(Remainder of this article continued in the print magazine…)

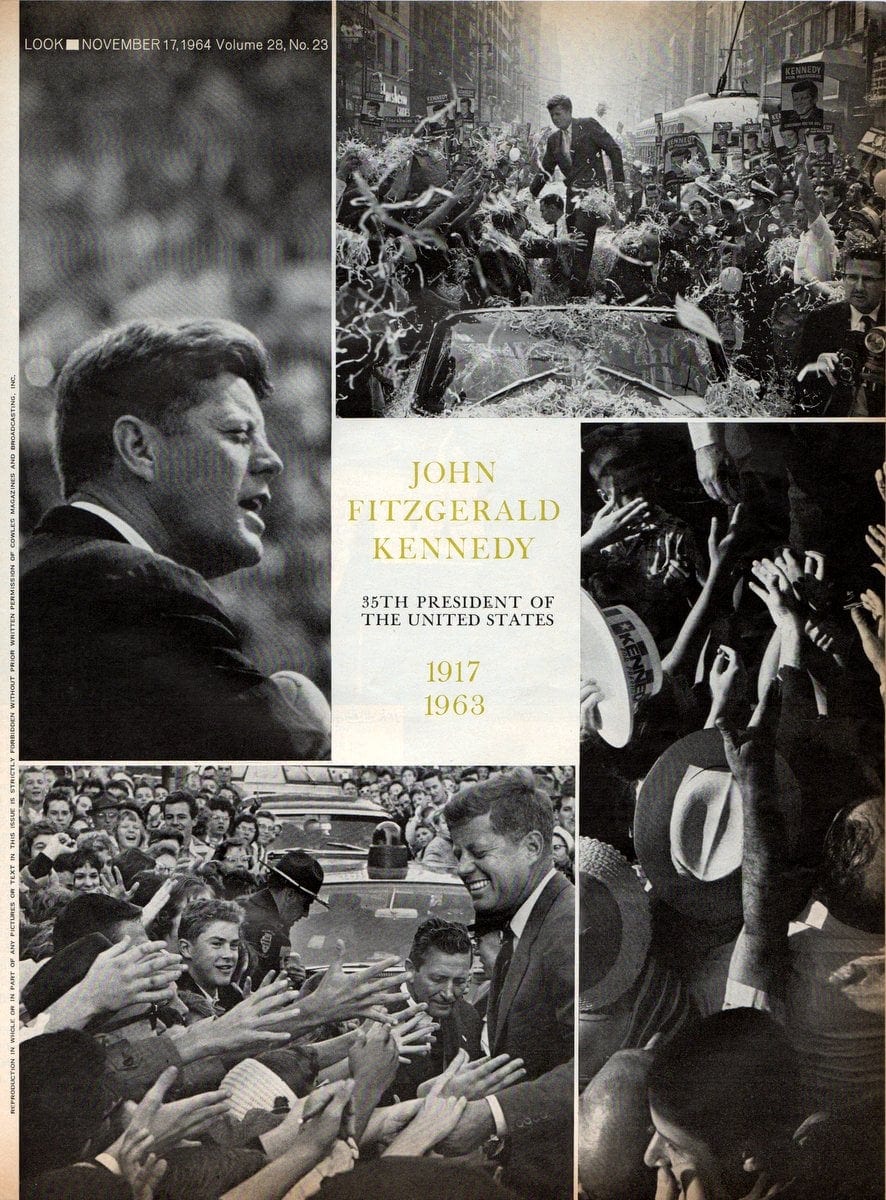

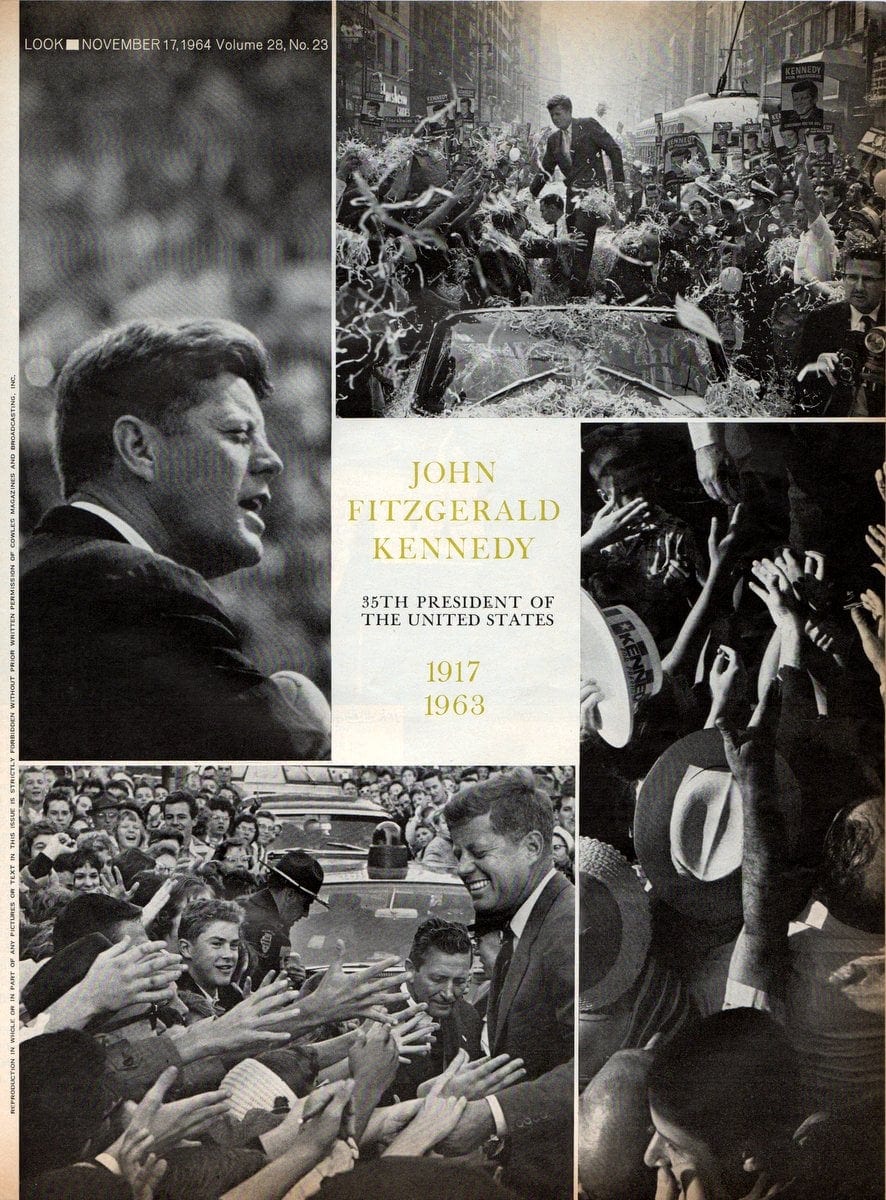

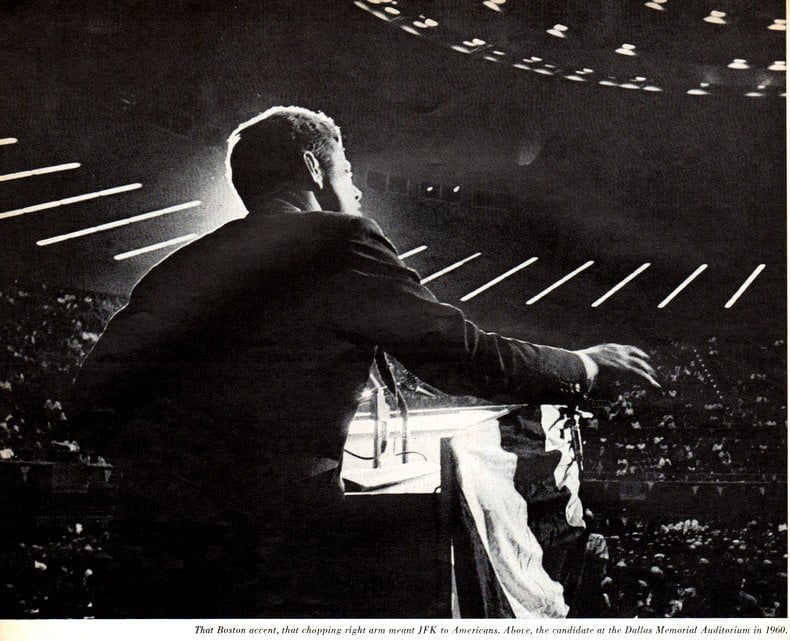

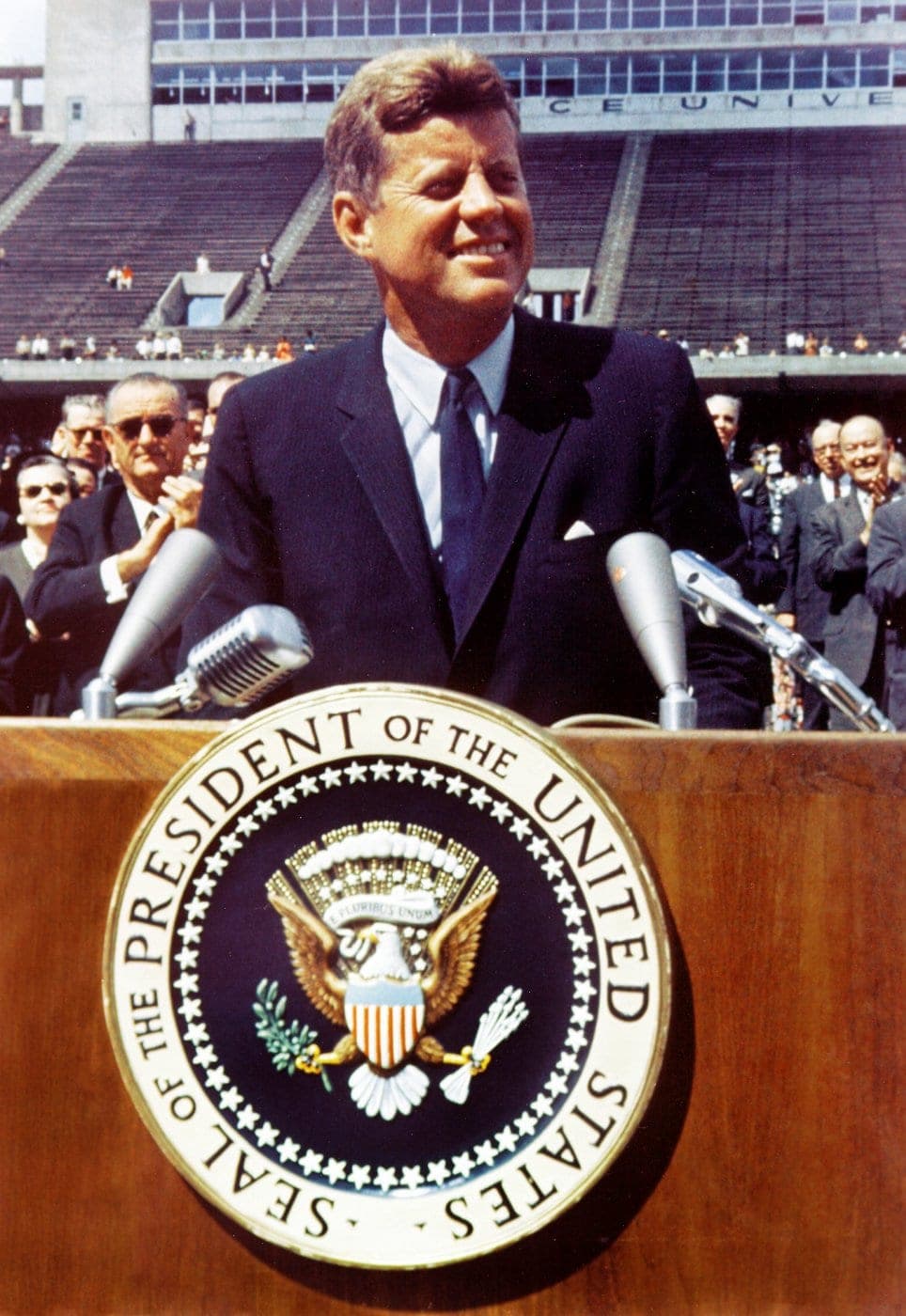

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 35th President of the United States

by Laura Bergquist, Senior Editor – LOOK November 17, 1964

From the fizzy early takeoff of the New Frontier to the heartbreaking end, I was a fascinated spectator, who dropped in at the White House off and on in the line of duty to check up on Kennedy happenings.

“Seeing the Tiger?” the White House guard would ask, and that set the tone: admiring, but not reverential.

JFK was the first President I had ever known, and somehow the idea was both stunning and exhilarating. For the first time in my life, the President of the United States was not an Olympian-remote, grandfatherly figure, but a contemporary — brighter, wittier, more sure of his destiny and more disciplined than any of us, but still a superior equal who talked your language, read the books you read, knew the inside jokes.

In a world can by old men, he was a leader born in the 20th century, and when they said a new generation had taken over, you realized it was your own. That made you nervous, knowing how fallible we were.

Emotions about him seemed to vary with age: The young adored him, youthful leaders of the turbulent nations aped his style, while old New Dealers in their 50’s often didn’t feel quite comfortable with the cool, dry pragmatism of this New Frontiersman.

I had a critical, proprietary interest in that White House: If he pulled a boner, you argued with him in your head, or sometimes in person; if he did something splendid, you cheered him on with a note; if you ran across a useful bit of information in travels, say in Latin America, you felt he should hear about it. It seemed plain presumptuous, but an aide would urge you on: “Tell the President.”

You beefed when he seemed to move too cautiously, in civil rights, for example, forgetting that Lincoln was also shellacked for wasting time in persuading, temporizing and trying to hold the country together. You wondered if this quizzical, fact-absorbing rationalist had a real-guts understanding of the angry young revolutionists of the world, and not until he died did you realize, shamefaced, he certainly got through to them.

He didn’t seem to rouse your emotions, as much as your mind. Yet you felt proud seeing him cut such a swathe in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, and empathized with his wry reaction after the first cold-bath meeting with Khrushchev and the Russians, when he turned to US Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson and said, “Tell me, are they always this way?”

I first began trailing him in 1956, just after he’d lost the nomination for Vice-President; Democratic insiders then pooh-poohed his quest for the Presidency as impossible — he was too rich, too glamorous, had too much father, and he wasn’t Adlai.

But in Columbia, SC, a conservative bastion, I heard him speak out on civil rights with a ferocious, startling candor. I knew then he was better than the glamour image that dogged and often irked him.

Still, who could share the passionate certainty his lieutenant Ted Sorensen voiced on that Southern swing, that here was the next President? Then there he actually was, the first Irish-American intellectual President in history, a man for whom even Greta Garbo would drop by the White House, and a man who didn’t forget us cats who knew him early. He hadn’t changed, though his time for banter grew ever shorter.

Still, for all his informality, a paralysis hit you when you entered that quiet oval office. He had a knack for derailing an interview, switching from the kind of corny personal question he liked least ( “What does it feel like to be President?” “I’m not good at couch talk” ) , to ask, “Do you know about the gold flow? No? Check Sorensen.” He thought you needed educating.

How, he’d muse, do you explain the complex issues of the ’60’s to people: the Common Market, balance of payments? Once, you recommended he read the novel Seven Days in May. Typically, he already had, and had pondered its theme, take-over of the US Government by the military. He could name a couple of Top Brass he thought might hanker to, he added.

If you were off for Cuba, he would give you homework: Read Henry Brandon’s latest dispatch from there in the London Sunday Times.

You might be talking to his secretary when out he’d pop to say, “I read your piece on the Dominican Republic,” and ask, whatever happened to that dwarf who specialized in exotic tortures for Trujillo?

Once, set for a noon session with him, I found his office jammed with his whole top echelon — from Secretary Rusk to Maxwell Taylor. I backed out quickly. It turned out big decisions were being made that day: The Russians had renewed nuclear testing.

You felt abashed intruding at all, with your minuscule concerns, on days like that — but came to learn that sometimes when pressures were fiercest, he liked to shift gears and talk about the minor things.

An aide of Mrs Kennedy’s once said she knew hell must be breaking loose in the West Wing when she got a barrage of calls from him: What about the fireworks for the King of Afghanistan? How long would they last? Did they have permission from the District of Columbia to fire them off?

Along with the staff, you waited for those JFK “funnies” that livened a dull, time-consuming ceremony in the Rose Garden, or the wit that flashed at a press conference. He clearly relished tangling with Goldwater, whom he liked.

It would not be fair, he said when asked by a reporter for a comment on a Goldwater statement, to add to the Senator’s problems. Goldwater, he pointed out, twinkling, had been so busy already that week selling the TVA, giving permission to military commanders to use nuclear weapons, involving himself in the Greek elections.

Once, after having been closeted for two days with some head of government, he went into the garden to address a religious group. A reporter, troubled by a particularly cloudy JFK sentence, asked Pierre Salinger to find out what he meant. “The President said to tell you he doesn’t know what he meant. He said that is just the way he gets after two days with so-and-so.”

Disbelief still assails me that he isn’t around, the White House seemed so much his natural habitat. He said in the inaugural message his hopes wouldn’t be fulfilled in the first 1,000 days, not even perhaps “in our lifetime on this planet,” and he got just a thousand. Historians must judge him now.

But he brought to that office far more than the style and quality belabored in the eulogies. He brought courage, rationality and spaciousness into American life.

He was the first President since Lincoln to marshal all his authority for the cause of the Negro. World War III was almost taken for granted, until he hammered home the thought that it was unthinkable. You could see him visibly growing in that office and feeling its burdens.

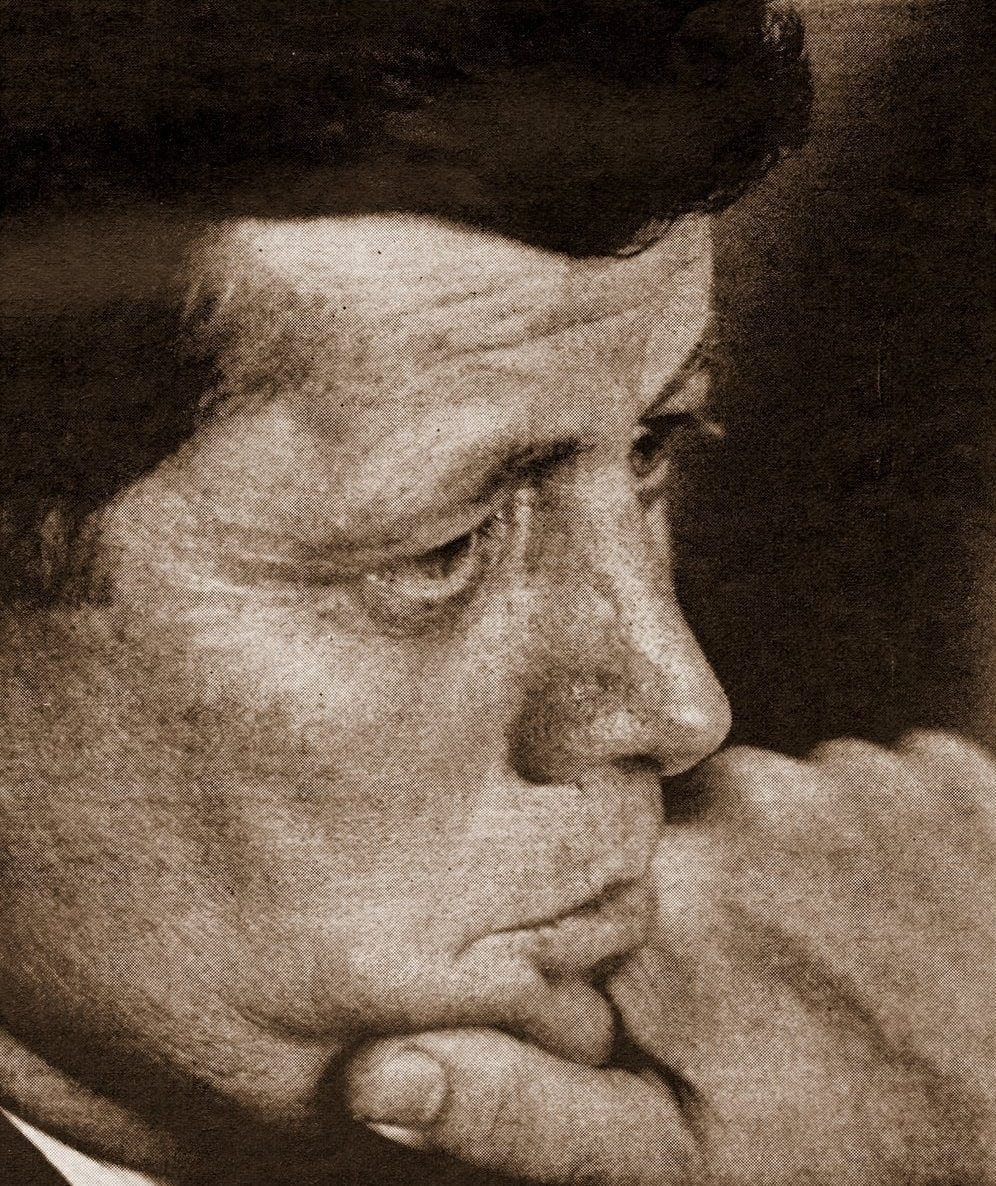

The last time I saw him, there was a somber, sobering quality about him, a dark vein of sadness I had never glimpsed before. So many months after the nightmare of Dallas, why is a sudden glimpse of him in a film enough to move you to tears? Perhaps, as Ted Sorensen found, his assassination affected many people more deeply than the death of their parents; the latter often represented a “loss of the past,” while he was an “incalculable loss of the future.”

Seven months later, his popularity showed no signs of waning. “What I admired especially,” said a young Arab sheik, “was his bravery over Cuba. But more than that, I felt he was of my own generation. He was really our President, too.”

No one would have been more astonished than that complex, fascinating man, who rarely voiced in public the deep passion he felt about events, who worried he wasn’t getting his message across, to find that he was not only admired all over the world, but loved.

The Warren Commission report brought back all the memories of his life and his death. A young girl interviewed in New York summed up our emotions quite simply.

“I’ll never get over it,” she said. Nor will I.

For John F Kennedy

November 26, 1963

Robert Frost, on Inaugural Day,

faltered and blinked because the sun

was in his eyes.

He said his words from memory then. Praise

to this green land, to its brave men.

He was old, his words soaring;

He is dead now.

And yesterday an air salute was roaring,

and twenty-one shots fired, and a caisson

with riderless black horse rode through the city

to take a younger man than Frost to rest.

Thinking hurts my chest.

What a grim liaison

of dim-eyed poet, clear-eyed President.

Is history a blur of sunlight on type

and memory the only true escape?

What has it meant, the talent of young men,

the one we mourn today, whose widow wears crepe?

Thank you for pomp, the endless ceremony

that tired even us who were not there.

There is safety in motion;

just moving on was how the pioneer

bore what there was to bear.

Whose woods are these? I think I know.

As that pale widow goes, so goes the nation.

– Claire Burch