The show arrived during a period when American sitcoms often centered on family life or rural settings. By moving Gomer from Mayberry to a military base, CBS kept the tone audiences loved while introducing a new backdrop shaped by order and discipline. The friction between Pvt. Gomer Pyle and Sgt. Vince Carter, played by Frank Sutton, gave the series its rhythm. Carter barked commands; Gomer responded with wide-eyed sincerity and an unfailing “Yes, sir.” The humor leaned on character rather than topical references, which helped the show remain accessible week after week.

Contemporary coverage reveals how quickly the series found its footing. A 1965 newspaper feature noted that Gomer Pyle USMC ranked in the top 10 soon after its debut and that Nabors had been singled out by trade publications as a standout new personality. That kind of response reflected both strong writing and the public’s connection to Nabors himself. His screen presence felt unpolished in a way that viewers trusted. Television director Bob Sweeney observed that audiences instinctively rooted for him, a quality that translated into steady ratings.

Nabors’ path to stardom also fit the era’s television narrative. Before acting, he worked as an apprentice film editor and performed at a Santa Monica cabaret, where his singing drew attention. His discovery by Andy Griffith linked him to a proven star who understood the pressures of sudden fame. Interviews from the time emphasized Nabors’ modest habits, his close ties to friends and family and the guidance of manager Richard O. Linke, who kept his schedule balanced as production and public appearances increased. Profiles often asked whether success had changed him, a common theme in 1960s celebrity journalism.

Gomer Pyle USMC thrived from 1964 to 1969, producing 150 episodes during a period of significant cultural change in the United States. While headlines elsewhere grew more serious, the show offered a steady half-hour built on personality clashes and gentle lessons about patience and respect. Its popularity underscored television’s role as a shared evening routine, where familiar characters returned each week on a dependable schedule.

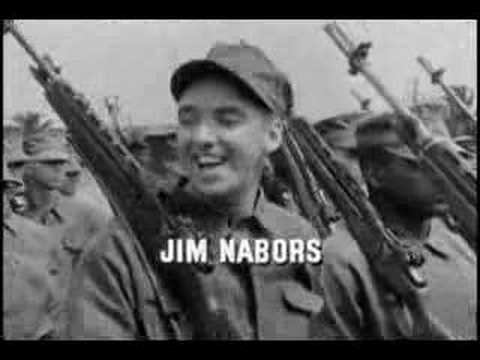

Below, we’ve gathered original photos, press clippings and features from the height of Gomer Pyle USMC. They show how the series was presented to viewers, how Jim Nabors was profiled at the peak of his fame and how a soft-spoken character in uniform became a lasting part of 1960s television history.

Has overnight success on Gomer Pyle, USMC changed Jim Nabors? (1965)

by Edgar Penton – Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia) March 14, 1965

No matter how you pour it, Jim Nabors’ cup is running over.

Gomer Pyle, USMC, in which he plays the title role, has consistently been in the top 10 of the nation’s television programs since making its debut on the CBS Television Network last fall. The show airs on the net 9:30 to 10:00 p.m., EST.

In recent weeks alone he has garnered the following honors by the trade press: ”personality of the year,” “the most promising “new male star,” and ”the outstanding new personality.”

When he went home to Sylacauga, Alabama, at Christmas time, he received a hero’s welcome, and the town’s population of 10,000 tripled for the occasion.

Has overnight success changed Jim Nabors? It’s not an easy question to answer.

A scant four years ago Nabors was an apprentice film editor at NBC, a job he had taken more for the benefits of the Southern California climate (he suffers from asthma), than to satisfy any show-business ambitions.

A shy, soft-spoken young man, he found Hollywood a lonely place. He began spending his evenings at The Horn, a Santa Monica, California, cabaret-theater that showcases young professional performers, primarily singers.

Anybody who frequents The Horn often enough is bound to attract the attention of the owners, Rick and Margaret Ricardi. Ricardi, one-time vocal coach and musical casting director at MGM and Twentieth Century-Fox, befriended Nabors.

Ricardi learned that Nabors had occasionally sung on a local radio station in the South, and had once recorded a rock’n’roll number that had failed to gross the $15 fee Nabors was paid.

MORE: Jim Nabors’ Gomer Pyle sings (1964)

It took Ricardi four months to persuade Nabors to go onstage and sing a couple of numbers, When Nabors finally did perform, he was enthusiastically received.

Nabors became a regular performer at The Horn, combining nighttime appearances with daytime film-cutting. Ricardi encouraged and coached him to the point that he was soon a polished entertainer — although still modest and shy, onstage as well as off.

Television director Bob Sweeney, who was later to direct Nabors in his first appearances on The Andy Griffith Show, says Nabors’ natural modesty and shyness are basic keys to his success.

“When Jim gets onstage you automatically feel sorry for him,” Sweeney says. “You want him to succeed. And when he does, you’re overjoyed.”

At the Horn, Nabors found his real profession.

It was here, too, that he met one of his closest friends, Paul Hiestand, an air conditioning design engineer with whom Nabors, a bachelor, has shared a small two-bedroom home in the San Fernando Valley for the past several years.

Nabors himself gives Hiestand a great deal of credit for helping him maintain his equilibrium during the heady days of excitement when Andy Griffith discovered him and made a place for him on The Andy Griffith Show.

MORE: Ron Howard: Andy Griffith’s Ronnie is all boy (1965)

“Paul takes everything in his stride,” Nabors once remarked. “He never gets excited about anything. If I came home bubbling over about my career, he’d take it all very calmly. It sure kept me from getting a big head.”

Hiestand is amused at the remark. “Actually,” Hiestand says, “I was often as excited about the way Jim’s career was going as he was. But I thought it was better for Jim if I took everything nonchalantly.”

One of the great stabilizing forces in Nabor’s rise was, and is, Andy Griffith. Griffith’s own rise to stardom had spanned a period of dozen years. He had benefited from having a longer period of time in which to absorb the impact of fame.

Nabors and Griffith, who live only three blocks apart, have been close friends since Griffith discovered the young Southerner at The Horn two and a half years ago.

“When Jim first appeared on my show,” Griffith says, “he was too insecure to change much — too unsure of himself.”

Nor is Griffith the type of man to let people around him put on airs. Once, just before the premiere of Gomer Pyle — USMC, Nabors arrived hours late at a party given at the Griffith home. He got a stern lecture from Griffith on the virtue of promptness.

MORE: ‘Hogan’s Heroes’ star Bob Crane on finding the humor in war (1965)

But lapses in thoughtfulness are rare indeed for Nabors. Nor has he ever forgotten the people who “knew him when.”

Nabors considers the Ricardis an extra set of parents, and frequently drops by their home or visits their cabaret-theater, where he occasionally gets up and performs.

This winter, he brought his widowed mother to California to spend a few months with him. In the course of the year, he’ll invite a whole string of relatives to visit him for varying lengths of time.

He has to make time to spend with friends and relatives. And he does. Nabors not only spends 12 to 14 hours a day, five days a week, at the studio, but his weekends are filled with personal appearances for new episodes.

ALSO SEE: The Andy Griffith TV show’s success & that catchy theme song (1960s)

Richard O. Linke, Nabor’s and Andy Griffith’s personal manager, keeps a tight rein on his clients’ activities.

“Jim’s first responsibility, professionally, is to the show,” he says. “He’d probably never have had an hour to himself if we didn’t watch his schedule carefully.”

Does Linke believe that Nabers has changed? “Sure he’s changed,” Linke says. “You can’t turn a guy from an unknown into a favorite of millions without his changing some. But his values haven’t changed, and that’s the important thing, isn’t it?”