How to choose a husband, according to 1920s etiquette writers

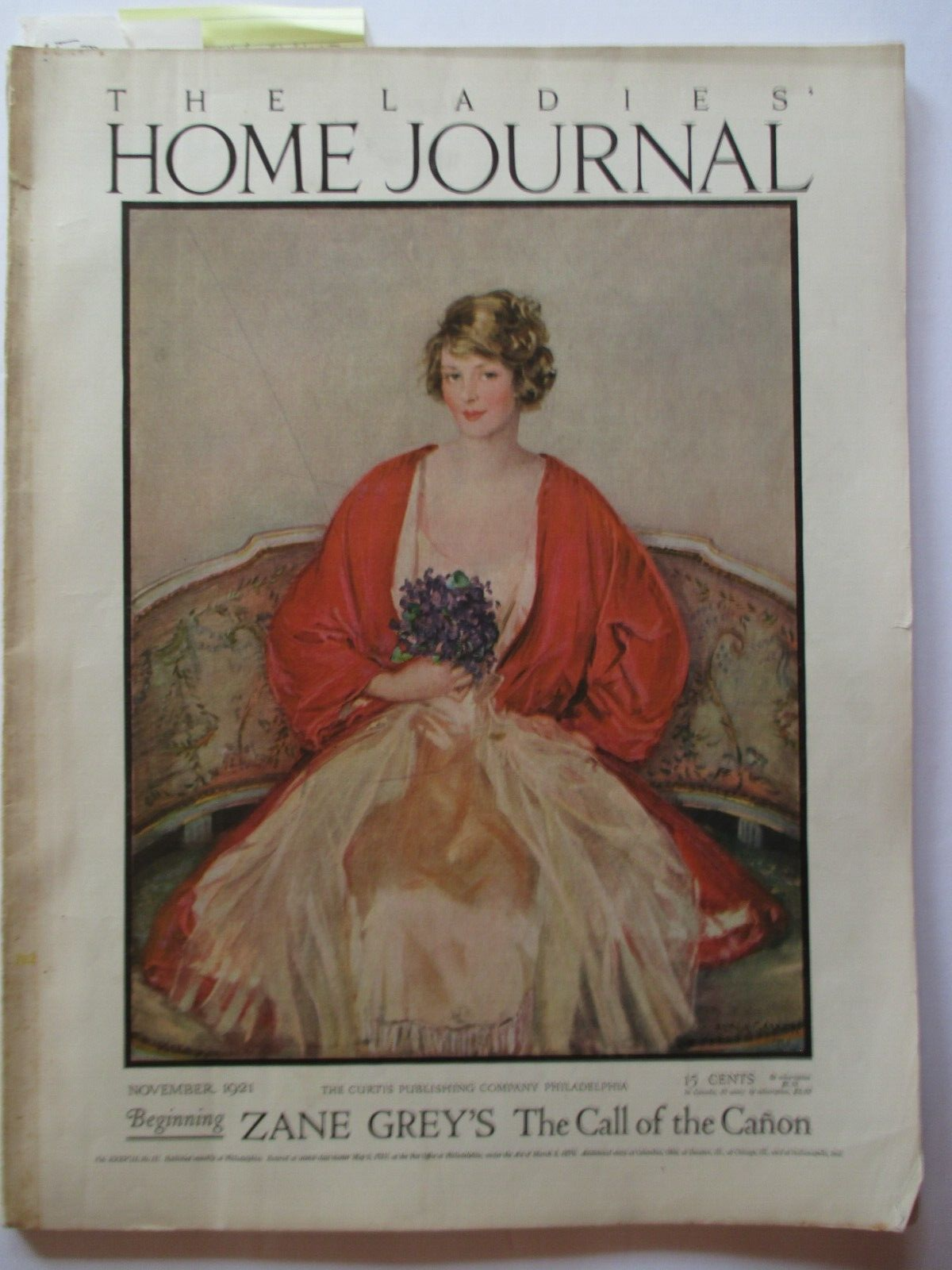

In November 1921, one such piece advised women on what to look for (and what to avoid) in a prospective husband. The author treated the topic with a blend of sharp observation and early 20th‑century etiquette sensibility — part moral instruction, part social coaching, and part wry commentary on human behavior.

Manners as a window to character

One of the earliest cautions in the advice is about the small, everyday behaviors that reveal deeper traits. A man who picks his teeth in public or drums on a table, the etiquette guide argued, is likely to continue such habits in married life. These actions were seen as more than mere lapses in decorum; they were taken as signs of underlying respect (or lack thereof) for others’ comfort. In a world where parlor manners still mattered, such habits were interpreted as evidence of a man’s quality — or lack of it.

“The past” and sincerity

The 1921 guide also addressed how a man speaks of his past. Contemporary etiquette writers expected a future husband to refer darkly and remorsefully to youthful indiscretions, as if his upbringing under a guiding woman (ideally his wife‑to‑be) would redeem him. If a suitor didn’t mention a past at all, the article suggested he might be overly conceited or hiding something more troubling — a “lurid” past too shameful to disclose. This reflects a period belief in the redemptive power of marriage and the idea that a woman’s influence could shape a man’s character.

The saintly suitor — and why perfection isn’t ideal

The advice takes a surprising turn when it comes to men considered exceptionally good. According to the 1921 etiquette writer, a suitor who proclaims himself a saint by temperament — unwaveringly upright, unvaryingly virtuous — may not be the most desirable husband. The concern is that such a man, secure in his own self‑image of perfection, might lack patience for his wife’s imperfections and become overly critical. This point acknowledges what modern relationship observers might describe as imbalance or lack of empathy: Someone who gives little thought to their own flaws often struggles to offer compassion to others.

Courting versus living together

Another section reflects an enduring truth about relationships: courtship and marriage are not the same thing. The guide warns against assuming that generosity during courtship translates to generosity in marriage, especially when money and daily life pressures enter the picture. A suitor who flashed cash on dates might remain thrifty or withholding once the wedding ring is on the finger. The suggested antidote was simple and timeless: Set boundaries, know your own values, and make sure your partner’s behavior aligns with yours before making a lifelong commitment.

A choice of virtues and foibles

Perhaps the most surprising advice is how the etiquette writer characterizes “good men.” Rather than recommend flawless perfection, the guide suggests choosing a man with a mix of virtues and recognizable flaws. This mirrors a psychological insight that many modern relationship counselors echo: Compatibility isn’t about finding a perfect partner, but finding someone whose faults you can accept alongside his strengths. The author notes that mutual forgiveness will renew happiness more often than any idealized harmony.

What it tells us about the 1920s

Taken together, this advice paints a picture of early 20th‑century expectations around marriage, gender roles and personal behavior. It comes from an era when social rituals were more formalized, when public conduct reflected private character, and when magazines wielded real influence in shaping how women thought about family, relationships and domestic life. But beneath the etiquette and the period language, there’s a thread that still resonates today: marriage is about observing behavior over time, understanding character beyond charm, and recognizing that love — real love — is practice as much as passion.

Below, you’ll find a reprint of the original 1921 article to explore the language and attitudes of the time. Reading between the lines reveals both tips for choosing a husband in the 1920s, as well as ideas about commitment and companionship that continue to evolve into the present day.

- Molnar, Tim (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 234 Pages - 04/25/2025 (Publication Date) - Summit House Publishing (Publisher)

On how to choose a husband: Saving the man with a past

by Corra Harris

Do not marry a man who picks his teeth in the parlor or drums on the table with his fingers, not even if he is a millionaire. Leave him his tobacco, permit him to smoke with his feet on the piano, but do not marry a man who fights his own teeth in public places. It is a habit. He will never break it, because it is an indication of his quality, like the color of his hair.

Suspect any man who does not refer darkly and remorsefully to his “past,” from which you alone can save him. There is something fishy about his courtship if he fails to do this. It is out of drawing with the reverent deceit of an honest lover.

He may never have done an untoward thing. But potentially at least every man has a “past,” even if it is no more than the plumage of his imagination. He is right about it. He feels the truth instinctively. And this is the truth: every man who is saved in this present world is saved by a woman, whatever may be said about those who are not saved.

Therefore, if he never refers to his past, he may have one too lurid to mention, and to which he is determined to remain wedded. Or he may be too conceited to admit his faults, which is the meanest kind of weakness, defended by a vanity that you will find intolerable as his wife, but must endure. “Endure” is a term which belongs in the marriage ceremony; it will last better than the obsolete word “obey.”

How to choose a husband: Thousands of good men

There are thousands upon thousands of good men, so well established in their mere virtues that they have nothing to confess. By all means, marry such a man without fear of the monotony we instinctively associate with invincible integrity, because you will be delighted to discover that he has the usual faults, and you will have a life’s work endeavoring to correct them.

But whatever you do, do not marry a man who claims to be a saint. He lives too much in his own imagination of himself. He is nearly always an unconscious or a subconscious hypocrite. He will not live up to his professions with you, although he may do it with the brethren.

https://clickamericana.com/topics/love-marriage/how-did-he-propose-cute-engagement-stories-from-the-20s

You may trust him to behave discreetly under circumstances where the normal husband might vary slightly from your ideal of him, but you cannot trust this ignobly perfect man’s charity and patience toward you, his wife.

He will become a sort of malicious omniscience, with eyes fixed upon your faults and limitations. But the Lord himself cannot convict him of his own faults. He will commit pious transgressions against your peace and liberty. He will keep you in bondage to his bigoted prejudices against the most innocent pleasures. He is fundamentally mean, and he has an evil mind. And no law can defend a wife from the evil mind of her husband. It is the most subtle form of tyranny.

The only satisfaction you will ever get of him will be the privilege of saying to your friends, “My husband is such a good man!” And they will agree with you compassionately, knowing well that you and your children are the victims of his righteous persecutions.

Courtship not the same as marriage, and other advice about how to choose a husband

Do not infer because a man spends his substance freely for you during his courtship that he will be a generous husband. The oracles of matrimony show quite the contrary. At this point, marriage is always a leap in the dark. The poor young man might have been more generous than this rich one whom you have chosen because he was rich. Just resolve that you will not be skinned by a skinflint husband, and that you will not be extravagant and take your chances.

The safest risk as a husband is a man with three or four of the essential number-nine virtues, not the narrow toe-pinching kind, but the big, fine, gawky ones which make you laugh sometimes. And be sure he has the usual masculine faults to offset your own frailties, which you know you have, but he will not until his vision clears.

At first, he sees through the glass brightly, but presently your real shadow falls there. Then you are both in for the matrimonial verities, and it is wise to have a common sinking fund of faults to forgive each other.

You will discover that your happiness after marriage is more frequently renewed by mutual forgiveness than any other way.

One Response

I wish the article had shared what it means by the nine virtues,