Wayne’s career spanned five decades, and during that time, he starred in over 150 films. Known for his roles in True Grit and Stagecoach, Wayne became synonymous with the American West.

His portrayals of strong, silent heroes struck a chord with audiences, embodying traditional American values. However, his off-screen comments, particularly his views on race, have caused significant controversy. In a 1971 interview with Playboy, Wayne made deeply problematic remarks, including his belief in white supremacy, which have led to ongoing discussions about his legacy.

In his later years, Wayne did reflect on his career, but his political beliefs remained consistent, even as the cultural landscape shifted. Despite the adoration of millions, his remarks alienated others, particularly as social attitudes began to change. The complex nature of his legacy illustrates how a person can be both a cultural icon and a figure of controversy. While Wayne’s films continue to be celebrated, his personal views remind us that public figures are often more complicated than their on-screen personas.

We’ve put together a collection of articles and photos that give us a look into John Wayne’s life, especially his final years when he looked back at his time in Hollywood. Scroll to see what we’ve gathered about the Duke, and take a closer look at one of America’s most enduring icons.

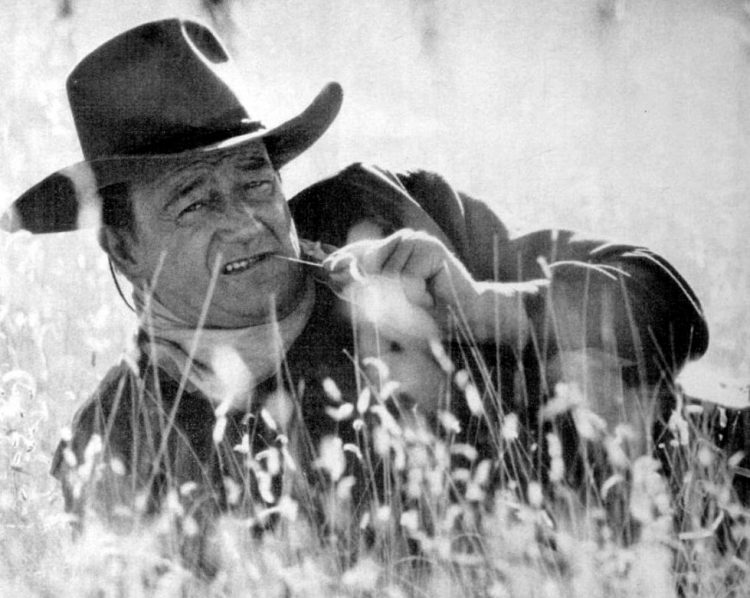

At 69, John Wayne rides tall with his fans (1976)

“John Wayne has an endless face and he can go on forever.” – Louis B. Mayer

By Kenneth Turan – Pittsburgh Press (Pennsylvania) September 10, 1976

Newport Beach, Calif. — A small group of dieticians sits quietly in John Wayne’s living room, planning a new weight-loss diet for him.

“He’ll be allowed a quarter-teaspoon of salt a day for three weeks,” one of them says, and Wayne, picking up on that, yells out, “Hell, I eat more salt than that on ice cream.”

“Will he be drinking milk?” the dietician asks.

“Not unless I have to,” Wayne growls, complaining after that he wasn’t being allowed to eat “anything but watermelon and gristle.”

John “Duke” Wayne is like that. He keeps doing these John Wayne bits that seem to come right out of his films.

After a discourse on his acting technique, he says, “Many fine actors get lost in their parts.” He pauses, looks real hard, says, “You very seldom see that happen to me,” and bursts into his hearty laugh. Cut and print.

Wayne’s study is nearly 60 feet long, an awesome place. A brilliant hoard of mementos, awards and decorations overflows on one wall.

There’s everything from some sand from Iwo Jima, courtesy of the US Marines, to an Oscar, courtesy of “True Grit.”

When Wayne shows you around, none of this seems to matter. What Wayne instinctively gravitates toward is the people, his people.

“There’s a picture,” he says, stopping suddenly before an old, slightly shaky color photo of four men on a fishing boat: Himself, John Ford, Henry Fonda and Ward Bond. The photographer: Gregg Toland, the man who shot “Citizen Kane.”

“It was down at the Gulf of Cortez near Baja, California. Everyone goes there now, but we went for years in the ’30s,” Wayne says, remembering.

“Duke” says he’s just human

Even after all these years, John Wayne has trouble with the way people think of him in mythic rather than human terms. “I have to go to the can like everyone else,” he grumbles.

He was “embarrassed” when his boat, a converted minesweeper called The Wild Goose, recently docked on the coast of Washington, and so many people crowded around to see him that “one poor woman got a little too far over, and, naturally, she hit the drink.”

Yet it seems almost impossible to deal with him other than as a way of life, a constant, an American tradition.

Even his family sounds legendary — his seven children from two marriages, ranging from a 40-year-old son to a 10-year-old daughter who is about half the age of the oldest of his 20 grandchildren.

Is it our fault if the 50 years he has been in the movie business seem like always?

No one, not even Wayne, knows exactly how many films he’s made. “A couple of hundred, and at 4 a.m. on a cold set, it feels like it,” is Wayne’s best guess.

“Every so often, I hear about one I’d forgotten. Sometimes I can’t even remember the leading lady’s name.”

In 1967, Time magazine called him “the greatest money-maker in movie history: the gross comes to nearly $400 million.”

And there is more to come. “The Shootist,” his latest [and final] film about an aging gunfighter dying of cancer, has been released to reviews, calling it his best work in years.

“Naturally, the fact about cancer and my background (he had a bout with cancer a dozen years ago) drew me to it,” Wayne says of the picture.

Wayne’s haggard look as gunfighter J. B. Books was more authentic than he’d planned: “I got the damn flu. I tried to keep working, but by the end of the week, I could hardly hold my head up. I had to take 10 days off and go to bed.”

Wayne is 69. With his hearty face, his broad forearms and broader hands, he hardly looks it, but there are signs.

As to his own view of himself, Wayne says, “I enjoy life to the extremities of my capabilities. I enjoy humor, I have the inclination to trust people, and I was raised by a man who said that lying was the only sin he couldn’t forgive me for.”

It’s an effort to believe there was a time when John Wayne was Marion Morrison, pre-law student taking courses at the University of Southern California, where he played football.

He had worked during a summer vacation as a property man on the Fox Film Studio lot and became friends with a director named John Ford. In 1929, Ford gave him the very small role of a racetrack tout in a film called “Hangman’s House.” And so it began.

Wayne has some very definite ideas about why his screen popularity never seems to dwindle.

“Number one, I like people, and I think that has a lot to do with it. And number two, I’ve been very lucky in the men I’ve worked with. Jack Ford and Howard Hawks and Henry Hathaway were just great for me, and Raoul Walsh — the lustiness he gave to pictures I thought was tremendous.

“The man I played,” he says, slowly, thoughtfully, “could be rough, he could be immoral, he could be cruel, tough or tender, but” — here his hand hits the table smartly — “he was never petty or small. Everyone in the audience wants to identify with that kind of character.”

What bothers Wayne, more than anything else written about him, is “this picture of me as an extreme rightist Republican.

“In my own mind, I’m liberal to the point where I will listen to every point of view, which takes me out of the extremist class on both sides.

“Yet I’ve had bad criticism of my pictures, because of critics trying to criticize my political leaning instead of my pictures.”

It’s time to leave now, but Wayne won’t let you go without a shot at some more of those photos.

In a corner, he introduces “my favorite people: Pappy (Ford), William Holden, Ward Bond, Bruce Cabot, Gen. Douglas MacArthur.”

All but Holden are dead, and as Wayne lingers over the photos, his vulnerability and his strong remembrance of things past becomes clearer.

In fact, the most animated, the most alive and vibrant he’d been all day came when he’d talked about the times that were no more.

“There was an enthusiasm, whatever picture you were on. There was some wonderful chemistry about the business in those days.”

And today?

“Life goes on,” John Wayne says, “but there is nothing particularly better today than then.”