How old is St Nicholas?

St Nicholas was born in Patara, a city in what’s now Turkey, around the year 270. That makes him over 1,750 years old. His real-life story was one of early piety, religious leadership and eventually sainthood. He served as the Bishop of Myra and became known for acts of charity, the most famous being the quiet donation of gold to a poor man so his daughters could marry. This tale, told again and again, helped make Nicholas the patron saint of children — a role that continued to shape his identity across centuries and countries.

As the legend of St Nicholas spread across Europe, so did the customs that came with it. By the Middle Ages, he was honored in thousands of churches and towns, from Russia to the Netherlands. In Holland, he became Sinterklaas, known for bringing gifts to children on December 6. When Dutch settlers came to the New World, they brought that tradition with them. Though the Dutch influence is often overstated, it did help shape how Americans came to know old St Nick.

How St Nicholas became Santa Claus

By the 1800s, the name Santa Claus had taken hold, thanks in large part to writers like Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore. Moore’s 1822 poem, A Visit from St. Nicholas (better known as The Night Before Christmas), introduced the sleigh, the chimney visits and those eight tiny reindeer. That version of Santa was inspired by old St Nick but reimagined through an American lens — less bishop, more bearded gift-bringer in fur-trimmed red.

- Hardcover Book

- Cottage Door Press (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

By the end of the 19th century, Santa Claus was a cultural mainstay. President Benjamin Harrison even planned to dress as Santa for a White House Christmas celebration in 1891, telling the press he hoped others would do the same. That same year, a Minnesota newspaper published a short piece explaining how St Nicholas became the patron saint of children, referencing the gold-for-dowry story that had followed him for centuries.

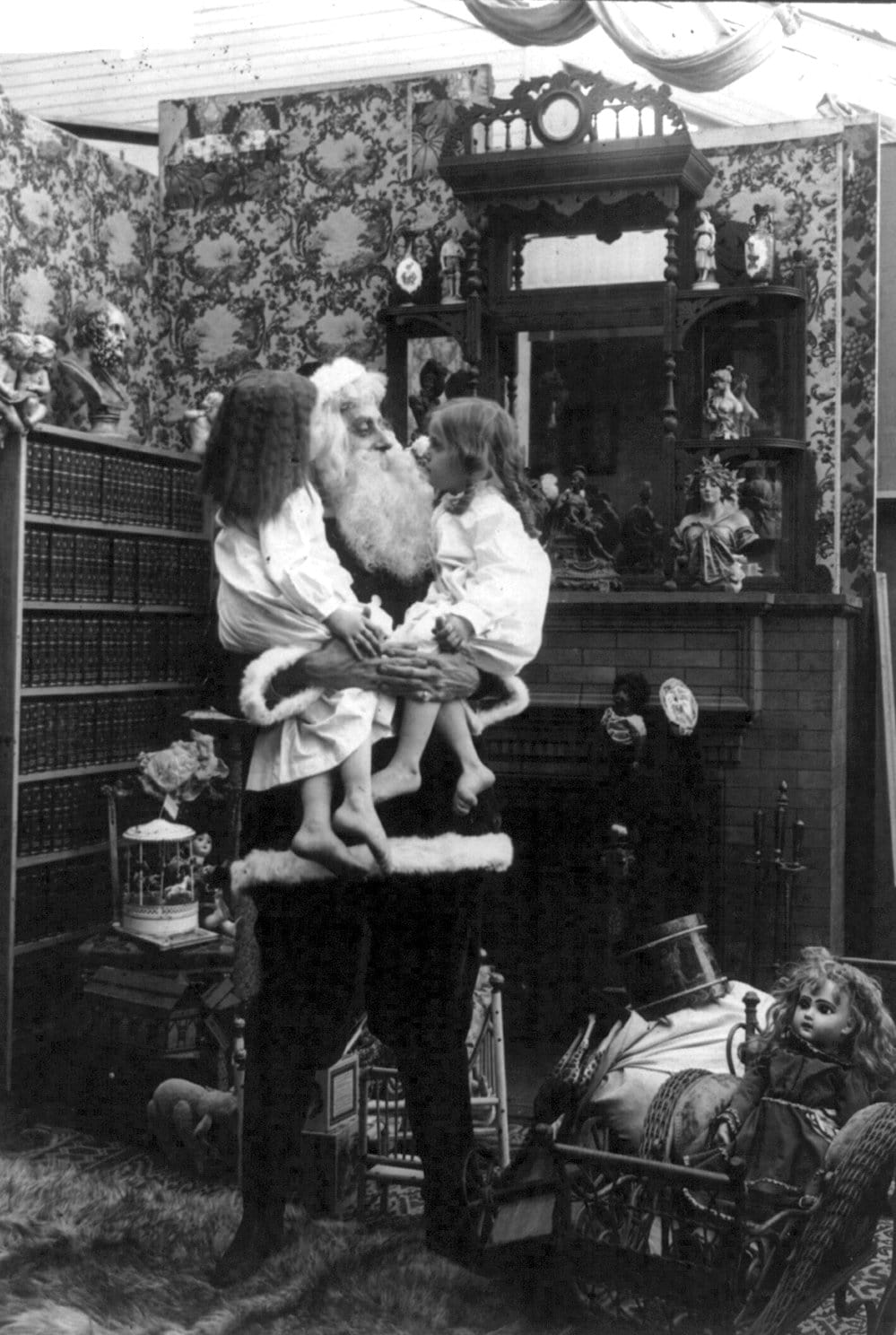

To show how the legend of old St Nick has been remembered, reinterpreted and celebrated, we’ve collected vintage photos and original articles — including that 1891 newspaper clip and classic postcards — that help tell the story of how a saint became Santa.

St Nicholas: How he came to be considered the patron saint of children

A pretty Catholic legend tells how St. Nicholas came to be considered the patron saint of children.

One day passing by a wretched house, he heard weeping within. Stepping softly to the open window, he heard a father lamenting the wretched fate to which his three lovely young daughters were doomed by poverty.

St. Nicholas’s gentle heart was touched. He returned at night, and threw in at the window three bags of gold, sufficient for the dowry of the girls. His kindness to them and to many others equally wretched made him regarded as the especial benefactor of children.

In Russia, he is revered as the chief saint of the Greek Church, but in Germany, Switzerland, Holland and Austria, it is as the children’s saint that he is chiefly honored.

The good Dutch burghers who founded New Amsterdam placed the little settlement under his care. It has grown to be the great city of New York, but his name is no less honored in the splendid metropolis than in the humble Dutch town.

Our Santa is a New Yorker (1963)

by Duncan Emrich, The Times Sun, December 15, 1963

The long road that led a certain Nicholas of Patara from the middle east to america had its crucial turning in Manhattan. And it wasn’t only the “Night before Christmas” poem that gave him his present form and status. This account of Santa’s travels was written by a former chief of the folklore section of the Library of Congress.

The road and seaway from Myra in Asia Minor to your street corner and chimney at Christmas is a long one, and was long in the building. Nevertheless, it is there, and one traveler voyages the incredibly long and circuitous route each year. He is somewhat metamorphosed, to be sure, as a result of the journey, but he is still one and the same: St. Nicholas and Santa Claus.

Tradition has it that a certain Nicholas was born in Patara in Lycia, that he led a holy life even as a youngster, was imprisoned and tortured for the faith under the reign of the Emperor Diocletian, but released under the more tolerant Constantine. He attended the Council of Nicaea as the Bishop of Myra, and died on Dec. 6 — his saint day — 43 A.D. Beyond that nothing, except the cult and the legend.

The veneration of Nicholas begins sometime before the year 430 A.D. when the Emperor Justinian built the first church in Nicholas’ honor in Constantinople. The cult spread through the Eastern church, and he became the patron of Moscow and of Russia, giving his name to czars and, if only by chance or inadvertence, to commissars. Nikita is a diminutive form of the name.

In the West, admiring citizens of Bari, Italy, organized an expedition in the year 1087 against Myra (then held by the Saracens), seized the Saint’s bones, and brought them back in triumph to their city. A basilica was built in honor of the relics, and an annual pilgrimage was instituted which is still immensely popular.

The cult reached Norway, where Nicholas joined Olaf as a patron saint. He is the patron of Aberdeen. In England, where St. George is patron, there are 204 churches dedicated to that saint, but 446 to St. Nicholas. Even before the year 1500, it is estimated that there were more than 3,000 churches dedicated to St. Nicholas in Germany, France, Belgium, and Holland. Besides Czars, five popes were named for him, and a king of Montenegro. And he is the special protector and patron also of maidens, children, sailors, pirates, pawnbrokers, merchants and students.

This brings us to the legends. Various tales describe Nicholas as the protector of children, and in another story, which represents him as a benefactor of maidens and virgins, he saves the daughters of an impoverished neighbor from a life of sin. Out of the fusion of these elements, there developed throughout Europe, and particularly in Holland, the folk custom of secretly giving gifts — nuts, apples, and small presents hidden in children’s shoes and stockings — on Dec. 6, St. Nicholas’ Day

New Yorker

St. Nicholas, though, remained for centuries a long-robed, bearded figure riding a horse, or making his rounds with horse and cart. He was still pictured as a saint and a bishop of the church. How did he turn into Santa Claus, and why did the day of giving move from the 6th to the 25th of December?

The answer to the shift of date lies in Europe, and two factors are involved. The first was the very natural tendency for all minor celebrations in December to gravitate toward the great feast of Christmas, a date on the Christian calendar coinciding with earlier pagan winter festivities and with the Roman saturnalia. The second factor was the Reformation in northern Europe, when the reformers attempted to wipe out all veneration — and even memory — of the saints.

They were successful, but not altogether. Under attack, St. Nicholas went underground to pop up under different disguises: Pere Noel in France, Father Christmas in England and Knecht Uprecht and Kris Kringle in Germany. The corpulence, however, the roly-poly person — that is the contribution of America, and specifically of New York City. Santa Claus as we know him is a New Yorker.

Now it has been somewhat widely but erroneously believed that the Dutch settlers in New Amsterdam introduced our Santa Claus. Actually, in spite of the fact that the Dutch corruption of the words Sinta Nikolaas into Sinterklaes existed in the Old World — and presumably in the New — the Dutch in New Amsterdam had little to do with him.

But the Dutch of New Amsterdam did provide Washington Irving the inspiration for his Knickerbocker History in 1809. And in that book there are some 25 references to St. Nicholas and Santa Claus. The immense popularity of Irving’s book served to introduce — or reintroduce — St. Nicholas to the American public. The good saint, remember, had never taken strong foothold in America: without Irving’s work there certainly would be no Santa Claus today. But still, in Irving, St. Nicholas is a figure of the church, bringing his gifts with horse and cart.

Slightly more than a decade later, however, in 1821, there appeared in New York a small juvenile called “The Children’s Friend,” which contained eight quatrains devoted to “Santeclaus,” whom it exhibited riding in a sleigh drawn by exactly one prancing reindeer. So far as we know this is the first reference to the reindeer and sleigh now associated with Santa Claus. They are both purely American inventions, and never existed in any European tradition.

Dutch image

Both the sleigh and the reindeer — and perhaps even Santa himself — might have quickly expired, though, had it not been for Clement C. Moore, an Episcopal clergyman in New York City and the son of the bishop of New York. In 1822, at the Christmas season, Moore wrote a poem for his children. The poem was “A Visit from St. Nicholas,’’ or, as it is more widely known now, “The Night Before Christmas.”’ At first, Moore thought the poem beneath his dignity, and would not acknowledge authorship of it until 1837, when it was published in a compilation of local poetry.

Moore had certainly read Irving, but in his creation of the poem he did one thing which seems not to have been noted before. From Irving and the Dutch tradition he drew St. Nicholas, the traditional St. Nicholas. But from his past reading of the Knickerbocker History, Moore remembered most vividly the descriptions of the fat and jolly Dutch burghers with their white beards, red cloaks, wide leather belts, and leather boots.

Thus, when he came to write a poem for his children, the traditional and somewhat austere St. Nicholas was transformed into a fat and jolly Dutchman. Also, from The Children’s Friend of the year before, which he had probably purchased for his own youngsters, he drew not one lone reindeer, but the now immortal and fanciful eight.

In the same year, 1837, when Moore’s poem appeared in book form, Santa Claus sat for his portrait in oil at — of all places — the United States Military Academy at West Point. The painting was done by Robert W. Weir, professor of art at the Academy, and shows a fat and jolly Santa with a “finger aside of his nose” about to ascend a chimney after filling the stockings beside it. His cape is red and white-furred, and the bag on his back is full of presents.

In the years immediately following, Santa Claus appeared at Christmas time on the small pocket-sized advertising cards of New York business firms. In that year Thomas Nast, the great cartoonist of the century, began drawing annual Christmas pictures of him for Harper’s Weekly, the most notable popular magazine of the era.

And then he reached the White House. In 1891, President Benjamin Harrison told an inquiring newspaperman, “We shall have an old-fashioned Christmas, and I myself intend to dress up as Santa Claus for the children. If my influence goes for aught in this busy world, I hope that my example will be followed in every family in the land.”

And so it has come to pass. The legend that began at Myra in Asia Minor, and traveled via Constantinople, Russia, and Holland to New York, now reaches nearly every household. It is quite a pilgrimage.