Grains sprouting and bread baking were the start of organic food in 1970

A 1970 article spelled out what was happening: More people were turning away from processed food, and looking for ingredients that hadn’t been treated with chemicals or additives. That meant grains like millet and barley, dried beans, unsulfured dried fruit, and loaves of dense sour rye packed with seeds. Some came from home kitchens, some from small bakeries, but the goal was the same — no shortcuts.

Sprouting grains at home was one of the first steps. You didn’t need a garden or a lot of equipment. People soaked wheat or beans in jars, drained them, and left them on the counter until they started to grow. At the University of California at Santa Cruz, students could choose a fully organic vegetarian menu that included things like kelp, tofu and nutritional yeast — foods that weren’t common in most dining halls at the time.

This kind of food came with its own rules. No pesticides, artificial flavors, nor preservatives. No antibiotics in meat. In many cases, that meant skipping meat altogether. Since most grocery stores didn’t carry what these new eaters wanted, food co-ops and small natural markets filled the gap.

Below, we’ve pulled together photos and pages from some 1970 articles showing grains sprouting, bread baking, and the kinds of organic foods that were showing up in kitchens as this trend kicked off.

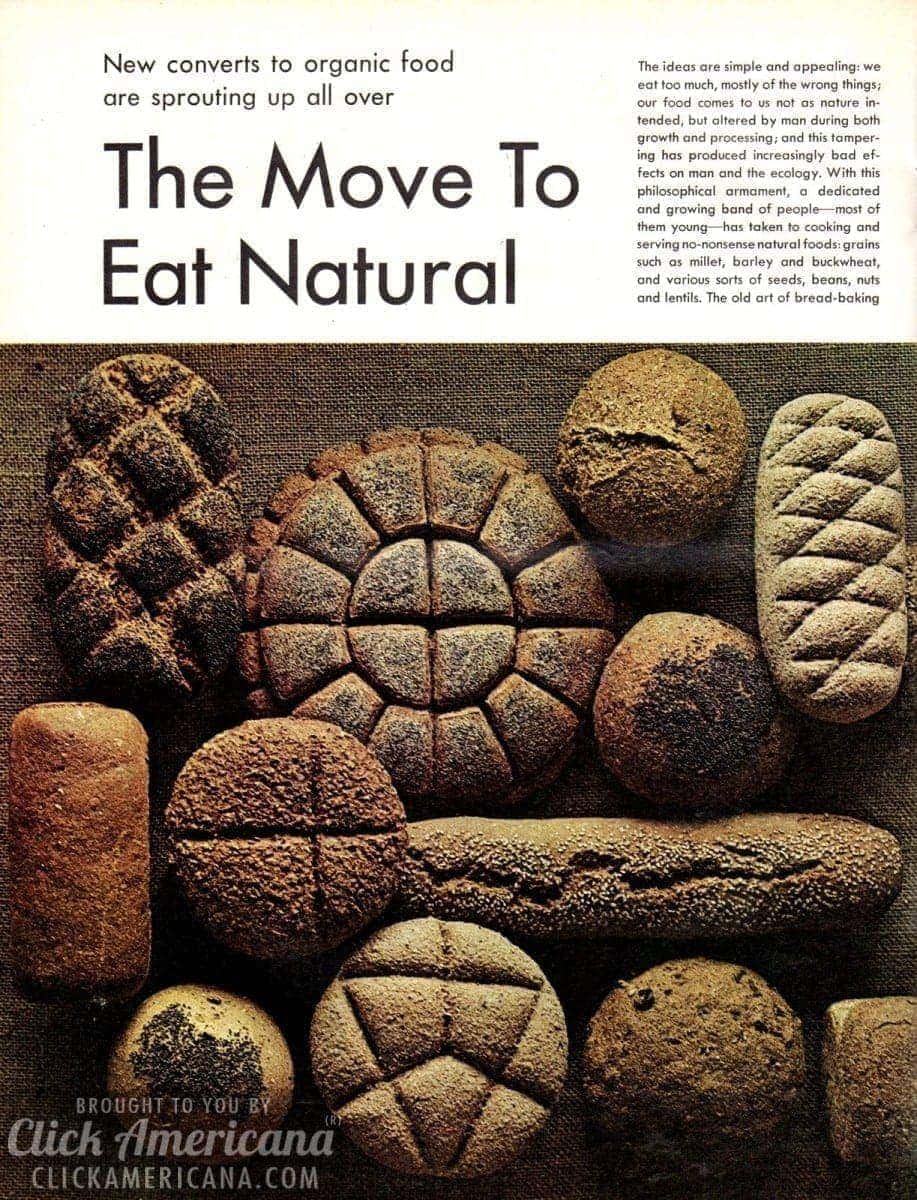

The move to eat natural: New converts to organic food are sprouting up all over

The ideas are simple and appealing: we eat too much, mostly of the wrong things; our food comes to us not as nature intended, but altered by man during both growth and processing; and this tampering has produced increasingly bad effects on man and the ecology.

With this philosophical armament, a dedicated and growing band of people — most of them young — has taken to cooking and serving no-nonsense natural foods: grains such as millet, barley and buckwheat, and various sorts of seeds, beans, nuts and lentils.

The old art of bread-baking is being revived. True devotees not only reject the instant world of brown-and-serve. They also insist, and will go to great lengths to insure, that all their food be grown organically, that is, without artificial help of any kind: no chemical fertilizers, no pesticides that linger in the soil. Meat must come from animals raised without benefit of antibiotics. Foods should be free of what they consider dubious chemical additives, whether for color or flavor or preservation.

To take care of these specialized demands, a nationwide subindustry has grown up.

Captions for page 2:

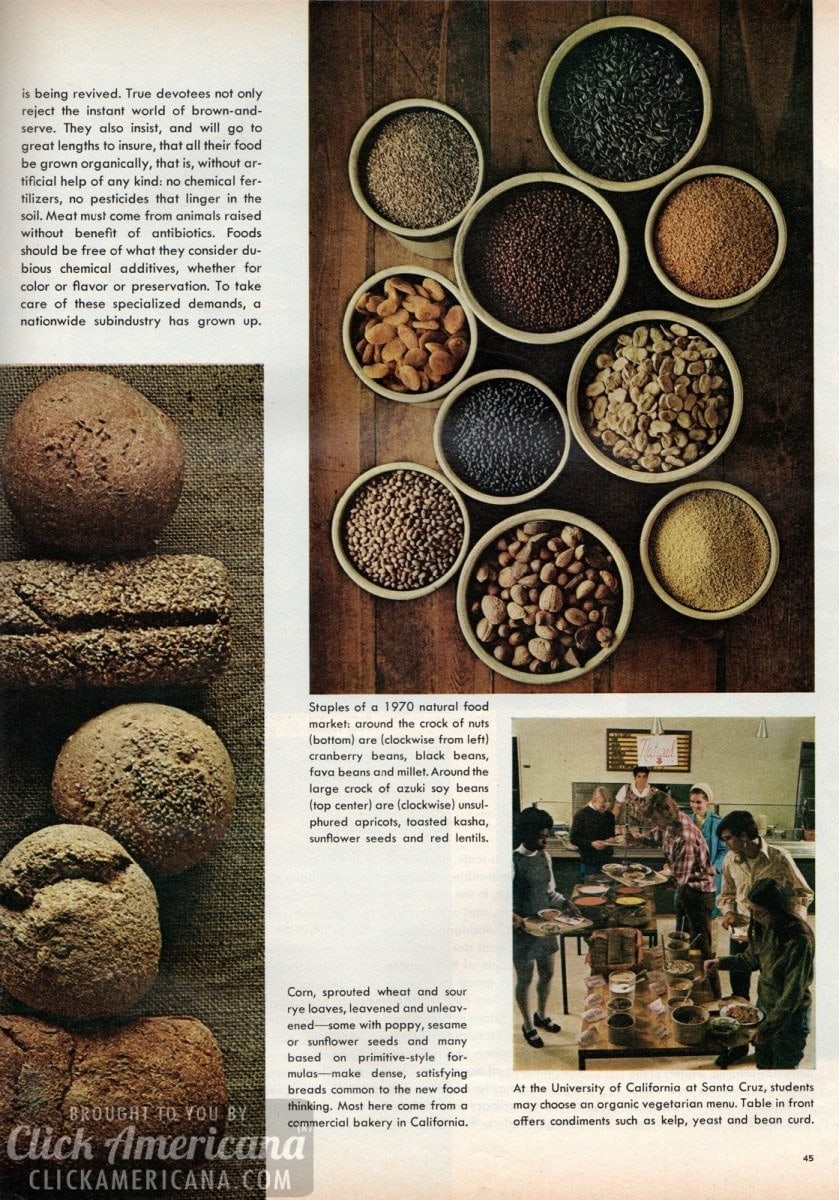

Staples of a 1970 natural food market: Around the crock of nuts (bottom) are (clockwise from left) cranberry beans, black beans, fava beans and millet. Around the large crock of azuki soy beans (top center) are (clockwise) unsulphured apricots, toasted kasha, sunflower seeds and red lentils.

Corn, sprouted wheat and sour rye loaves, leavened and unleavened — some with poppy, sesame or sunflower seeds and many based on primitive-style formulas — make dense, satisfying breads common to the new food thinking. Most here come from a commercial bakery in California.

At the University of California at Santa Cruz, students may choose an organic vegetarian menu. Table in front offers condiments such as kelp, yeast and bean curd.

Organic food: Hokum or healthy? (1972)

By Trudy Lieberman, Detroit Free Press (Michigan) March 6, 1972

Organic foods: Are they modern-day cure-all elixirs sold by modern-day hokum medicine men? Or are they a more wholesome alternative to the chemically-treated foods we customarily eat? The answer may lie somewhere in between.

Health food store owners and organic food wholesalers say people are tired of eating foods laced with preservatives, colorings and artificial flavorings, and sprayed with pesticides, herbicides and fungicides.

They say people want food that tastes like it did years ago, before chemical treatments became the norm.

“People no longer accept what they are told about food.” says William Garrison, general manager of the Erewhon Trading Co. of Boston, one of the largest wholesalers of organic food.

A typical health food store a few years ago used to be filled with vitamins, minerals, special dietary foods — and elderly customers. A typical health food store today is filled with organically grown green beans, organically produced honey. organic meats and sausages — and bearded, long-haired young customers.

Organically- grown foods are defined as foods grown without chemical fertilizers and not sprayed with pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals. No plant hormones are used, either. For some people, the definition also means those foods without chemical additives.

Organic meats come from animals that were not treated with hormones and were fed with grain that hadn’t been treated with chemicals.

Business is booming

The organic food industry is booming — a boom that may generate $400 million in business this year.

Glen Shue, a biochemist with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) division of nutrition, says that the organic food industry has become as much an entrenched interest group as the big producers of traditional foods.

Indeed, some worry that the organic food industry is becoming ripe for frauds and deceptions and that the consumer may not be getting what he pays for. And consumers are paying high prices for organic foods – sometimes more than double the price of non-organic counterparts.

The worst trap in buying organic foods is economic, Shue says. Some higher prices may be justified because farmers’ yields are lower, costs are higher and heavy farming equipment can’t always be used. But Shue believes prices are excessively high.

The organic food industry says that demand now outstrips supply, and this partially accounts for the higher prices. The industry predicts that prices will come down as soon as more fields come under organic cultivation.

But the FDA finds it strange that the supply is so low. There appears to be more organic food sold than is grown, according to Shue. One reason is that some foods are labeled as organically produced when in fact they are not.

Take apple juice, for instance. Much of it on the market hears the label “organically produced.”

“Unfortunately, there is little apple juice available that comes from organically grown apples. We just don’t have much of this,” says Garrison of the Erewhon Trading Co.

He says that when his company distributes organically produced apple juice, it is careful to tell buyers exactly under what conditions the apples were grown.

The Department of Consumer Affairs in New York City at recent hearings found that some retailers were slapping labels on non-organically produced food and selling it as an expensive organically-produced product.

The word organic

Another reason for the proliferation of organic foods is the use of the word “organic” itself. The word “organic” in chemistry means containing carbon, so technically almost any food can be labeled “organic” and really be organic. This same food may not be organically produced.

Says Garrison: “They (some retailers) are trying to make the customer believe the word ‘organic’ means the same thing as organically produced.”

How does the consumer know for sure that he is buying the real thing?

“By knowing who grew it,” says M C Goldman, managing editor of Organic Gardening and Farming, a Rodale Press publication.

Rodale Press has begun a certification program for organic farmers, but so far only 85 California farmers are participating. Farmers who qualify for Rodale’s certification program and other certification programs must have their soil tested for pesticide residues and may not use chemicals in the production of food.

Certification seals appear on food sent to retailers so they know it is properly grown. Certification is not universal, and consumers are on their own in determining whether something is really organically grown.

One rule of thumb is to ask the retailers for some guarantee that the food is the real thing. But this may not always produce satisfactory answers.

Shue contends that the only reason for eating organic foods is their lower pesticide content, and he terms this value “dubious.” He says the. FDA’s monitoring has shown that pesticide levels in foods are insignificant. Consumers Union (CU), the non-profit product-testing organization in Mt. Vernon. N.Y. recently sampled six jars of honey — three purchased in a health food store, and three in a supermarket. It found none of them to have pesticide residues.

George Pollak, CU’s food division chief, believes it is desirable not to eat chemicals in food if you don’t have to because “we don’t know the long-term effects.”

However, he points out, there are trade-offs to be considered. Dried fruits not treated with sulfur dioxide may contain insect eggs that could hatch into larvae. Or some vegetables not treated with chemicals may not look as nice because insects may have nibbled on them. Whole-grain flours may contain more nutrients than enriched flours, but the wheat germ and oil could become rancid and the flour might spoil faster.

The FDA maintains that there are no significant nutritional differences between organically produced and non-organically produced foods. The organically produced foods might be fresher and have less vitamin loss because they are marketed faster.

Buying psychology, not nutrition

“Let your pocketbook be your guide. if your pocketbook can afford organic foods and you feel you are getting something, then buy them,” Shue said. “You’re buying psychology and not nutrition.”

Shue worries about exaggerated claims and nutritional misinformation connected with organic foods and the so called health foods, he says. For example. that there is no reason to buy lecithin — a fat that your body produces. Yet lecithin is a staple of many health food stores.

Federal food law says that if a special claim is made for a food, the claim must be supported by telling what portion of the minimum daily food requirements the food supplies. Many companies producing these foods make no claims on the labels. Shue says: “They get away with murder.”

A product called Garlic-Parsley Forte says this on its label:

“Derived only from whole garlic, whole parsley herb. When you take Garlic-Parsley Forte you get garlic in its most natural form.” The label further says the product is “a pure powder made only from whole fresh garlic and parsley concentrate. Both natural ingredients have been combined in equal amounts in a single, pleasant-to-take, eight-gram tablet. Try them and you’ll find Garlic-Parsley Forte to be a delightful new low-cost dietary supplement.”

The label never says what Garlic-Parsley Forte will do for you.

While a health food store may have some legitimate organically-grown products. it may also have some ordinary products.

This casual mix of the organic and the new organic may lead you to believe that the non-organic food has some special characteristics when in fact it does not. And you’ll have to ask questions to be sure of what you’re buying.

At a Detroit health food store last week, a one-pound can of coffee was selling for $1.49. A one-pound can of coffee usually sells for about 90 cents.

The label said the coffee was “culture ripened” and an “all-purpose grind.” Was his coffee special?

A clerk replied: “It’s pure coffee. It has caffeine in it. All coffee has caffeine.”